Sea Grant Investigators show that Sandy was not a worst-case catastrophe

Malcolm Bowman, chairman and founder of the New York New Jersey Metropolitan Storm Surge Working Group and a professor of physical oceanography at Stony Brook University, called for barriers to protect New York City after Hurricane Katrina overwhelmed New Orleans in 2005. In mid-October, he reinforced previous calls for such action during a coastal resiliency storm surge barrier boat tour in New York City. Credit: James Estrin/The New York Times

— By Chris Gonzales, Communications Specialist, New York Sea Grant

New York, NY, October 20, 2017 - As the fifth anniversary of Superstorm Sandy rolls around, Malcolm Bowman, a professor at the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences at Stony Brook University, sometimes encounters a question:

“Was Sandy a worst-case scenario?”

“No!” he says. “Had Superstorm Sandy made landfall at slightly differing times, locations and stages of the tide, peak water levels could have been up to 1 1/2 feet higher than experienced. And that would have caused even more devastation, loss of life, and human misery. So the rallying call must always be: ‘Never again!’”

Bowman is part of a team, led by Brian Colle, that published a paper in the Journal of Marine Science and Engineering on the topic. (1)

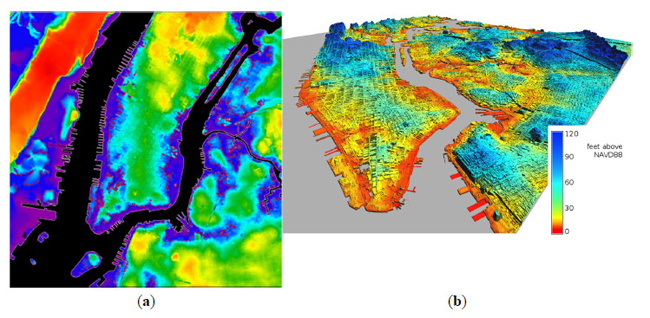

In their paper, they describe simulations of storm surge for New York City using two different models. In short, flooding could have been much worse.

Predicted Sandy inundation of central New York City (a). Isometric projection of simulated flooding of Manhattan, Queens, and Brooklyn (red and orange colors) (b).

In 2014, Bowman completed a project with funding from New York Sea Grant to investigate just how much.

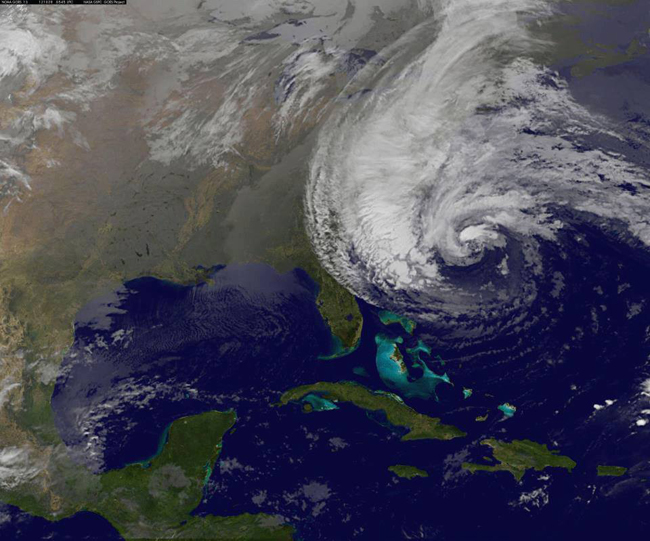

Superstorm Sandy, which struck metropolitan New York, New Jersey, and Long Island, resulted in 72 deaths and over $50 billion dollars in property damage.

The storm surge tide was more than 14 feet above mean lower low water at the southern tip of Manhattan, the largest event of its kind in 150 years of recorded history. Tropical storm force winds extended over 310 miles from the storm center.

A number of scientists agree that observed flooding was not a worst-case scenario. (2) (3)

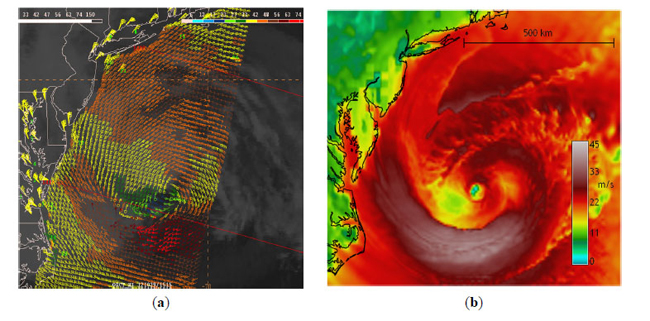

Red bands illustrate extreme surface winds during Superstorm Sandy.

The scientists are trying to answer a number of questions: If winds and sea level pressure are well-predicted, can a storm-surge model predict surge events? How much worse might flooding have been?

Relatively modest differences in storm track and intensity resulted in very different storm surge predictions. In 20 percent of simulated cases, storm surge was much worse.

It’s a big question with a simple answer: The surge could have been worse, and the time to prepare is now.

References

(1) Colle, B., et al. (2015). Exploring Water Level Sensitivity for Metropolitan New York during Sandy (2012) Using Ensemble Storm Surge Simulations. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 3, 428-443; doi:10.3390/jmse3020428

(2) Georgas, N.; Orton, P.; Blumberg, A.; Cohen, L.; Zarrilli, D.; Yin, L. The Impact of Tidal Phase on Hurricane Sandy’s Flooding Around New York City and Long Island Sound. J. Extreme Events 2014, 01, doi:10.1142/S2345737614500067.

(3) Forbes, C.; Rhome, J.; Mattocks, C.; Taylor, A. Predicting the storm surge threat of Hurricane Sandy with the National Weather Service SLOSH model. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2014, 2, 437–476.

Sandy, made its initial landfall into the NY metro area as a superstorm (post-tropical cyclone with maximum sustained winds of 80 mph) on Monday, October 29, 2012 at 7:30 pm EDT near Brigantine, N.J. It was the 18th of 19 named storms and the second of two major hurricanes of the 2012 Atlantic hurricane season. Credit: NOAA/National Weather Service

On YouTube: Scientists Make Another Pitch for Barriers to Block Storm Surges

— Compiled By Paul C. Focazio, Interim Communications Manager, New York Sea Grant

New York, NY, October 10, 2017 - As reported by the New York Times, CBS New York, NJTV News (a New Jersey-based PBS-affiliate station) and other local media outlets, some 20 scientists and engineers departed New York City's Pier 62 aboard the Manhattan II in mid-October 2017 for a coastal resiliency storm surge barrier boat tour.

In their discussions, these experts explored how towns and agencies have responded to the threat of storms since October 2012's Superstorm Sandy

"There's an urgent need to investigate the role that a regional system of movable surge barriers could play in creating layered defense, to protect the metropolitan area from storm surges and sea level rise," said Bill Golden, President of the National Institute for Coastal and Harbor Infrastructure. "This system would be designed to work in tandem with planned local barriers and other strategies."

Stony Brook University investigator Malcolm Bowman, also Chair and Founder of the NY NJ Metro Storm Surge Working Group, said there is a need to address the fact that we live and work in a city built on an ocean.

"When Sandy happened, it was a combination of the storm’s wind, full moon high tide and the lack of defenses that lead to hundreds of homes being destroyed," he said. "Sandy damaged entire neighborhoods and left many without power. There have been projects and plans put forth to insure that our region is storm resilient as well as plans with flood gates and other types of barriers. But none have been constructed to date."

When it comes to future storms, Bowman predicted, “The question is not “if” a catastrophic hurricane or nor’easter will hit New York, but when." To address this, he added, "We have to be better prepared. There have been steps taken to infrastructure including subways and tunnel entrances, but patchwork and little response is not what is needed. We need bigger solutions."

A proposed six-mile-long Outer Harbor Gateway would stretch from Sandy Hook to Far Rockaway and would be supplemented by smaller barriers. It’s designed to remain open most of the time letting tides and maritime traffic flow freely. But, the gate would close in the face of impending storm surges.

“To keep back those occasional, but ever-increasing-in-danger storm surges associated with hurricanes and winter nor’easter,” said Bowman.

Proponents, including the National Institute for Coastal and Harbor Infrastructure admit that a surge gateway would be expensive — there’s no price tag. But, they noted, towns behind the gate could spend less on perimeter walls, and develop closer to the waterfront. They predicted an economy could thrive with a reduced threat of catastrophic storm impacts and urged officials to consider the proposal.

Credit: Bill Golden/NICHI

The resiliency proposal discussed by Bowman and others during the boat tour would create a system of storm surge barriers at four spots: (a) the Outer Harbor Gateway, between Sandy Hook, New Jersey, and Rockaway; (b) the East River between Queens and the Bronx; (c) East Rockaway, and (d) the Jones Inlet. Concrete structures would be installed at the locations and placed below sea level. Each structure includes a hinged steel gate that can rise to 92 feet from the water to create a barrier during high tide and surges.

“The gates are open 99.9 percent of the time,” said Bowman. “We keep back those storm surges associated with hurricanes and nor’easters.”

Like many of the other post-Sandy projects, the surge barriers have been in limbo because of funding issues and an ongoing review process.

But, as Bowman reminded, the city’s coastal areas have to deal with related environmental challenges: Rising sea levels and the attendant increased storm surges. By the end of the century, he predicted that sea levels around the city would rise by six feet.

A 3D animation showing design concept for the NYC Outer Harbor Gateway Storm Barrier. This animation was used in PBS NOVA's "Megastorm Aftermath," which aired on October 9, 2013.

More Info: New York Sea Grant

New York Sea Grant (NYSG), a cooperative program of Cornell University

and the State University of New York, is one of 33 university-based

programs under the National Sea Grant College Program (NSGCP) of the

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The NSGCP

engages this network of the nation’s top universities in conducting

scientific research, education, training and extension projects designed

to foster science-based decisions about the use and conservation of our

aquatic resources. Through its statewide network of integrated

services, NYSG has been promoting coastal vitality, environmental

sustainability, and citizen awareness about the State’s marine and Great

Lakes resources since 1971.

New York Sea Grant maintains Great Lakes offices at SUNY Buffalo, the

Wayne County Cooperative Extension office in Newark and at SUNY Oswego.

In the State's marine waters, NYSG has offices at Stony Brook University

and Stony Brook Manhattan, in the Hudson Valley through Cooperative

Extension in Kingston and at Brooklyn College.

For updates on Sea Grant activities: www.nyseagrant.org has RSS, Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube links. NYSG produces a monthly e-newsletter, "NOAA Sea Grant's Social Media Review," via its blog, www.nyseagrant.org/blog. Our program also offers a free e-list sign up via www.nyseagrant.org/coastlines for its flagship publication, NY Coastlines/Currents, which is published quarterly.