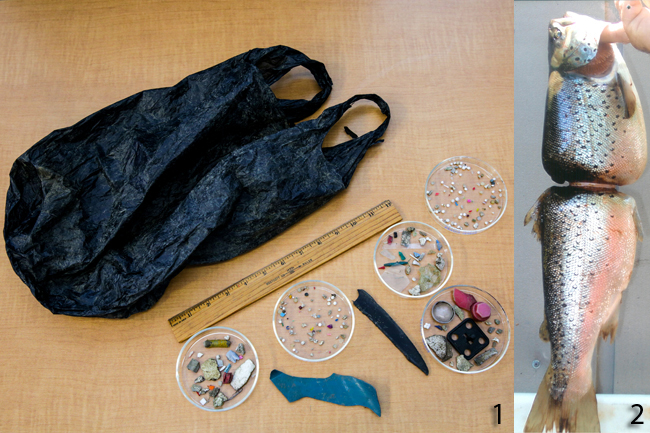

Images of throwaway polymers have become common in the media. Credit: Sherri “Sam” Mason, Penn State Behrend

— By Chris Gonzales, Freelance Science Writer, New York Sea Grant

Buffalo, NY, April 19, 2020 – A whale, having ingested plastic bags, lies stranded on the shore, fated to a premature death. A seabird with a stomach full of plastic fragments collapses from starvation. Vast patches of garbage awash with plastic debris are rotating in the middle of the ocean.

These vivid images in the media have led many people to think deeply about plastic pollution in the ocean. Scientists also have been concerned about those North American freshwater inland seas, the Great Lakes, to the point of realizing they lack some fundamental, basic information: How long does it take for common plastics to degrade in the water? What pollutants might be hitchhiking on the outer surfaces of these circulating, cast-off polymers?

A team of scientists led by Sherri “Sam” Mason of Penn State Erie, the Behrend College, set out to answer exactly those two questions. Joseph Gardella, a chemist at the University at Buffalo, also participated in the research. The project, funded by New York Sea Grant, ran for two years and was completed in 2019.

Two classes of useful devils

Sherri “Sam” Mason shows examples of some microbead-containing products. Microbeads (such as the ones in the inset photo) can be infused in personal care products. Researchers gathered them by rinsing the product through a sieve. Credit: Ted Sharon

“Plastics provide an ideal surface for persistent organic pollutants to adhere to,” said Mason.

She and her fellow researchers literally soaked new plastics in fresh water straight from the tap. In addition, they used a special machine to analyze bits of plastic they collected from the Great Lakes.

In particular, Mason and her team wanted to study silicones and fluorocarbons. Silicones are widely used in healthcare, aerospace, personal care, and many other human activities. Fluorocarbons are used in some aerosol propellants, coolants, and refrigerants, for a start.

“Persistent organic pollutants, or POPs, include chemicals well-known to be present in the Great Lakes, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), as well as lesser known, but increasingly common PFAS,”(1) Mason continued.

In the water samples they collected from the lakes, they found evidence of common plastics such as polyethylene, polypropylene, polystyrene, and others. These materials are typically used in food and product packaging, kitchenware and food storage containers, parts for cars and trucks, “living hinges,” (a flexible hinge made from the two rigid pieces it connects), building insulation, and textiles.

“All of these chemicals are known to have human health effects. One of my main concerns with microplastics in the lakes—and hence our drinking water—is their potential to bring these chemicals into the food chain, including us,” Mason said.

Degrading plastics

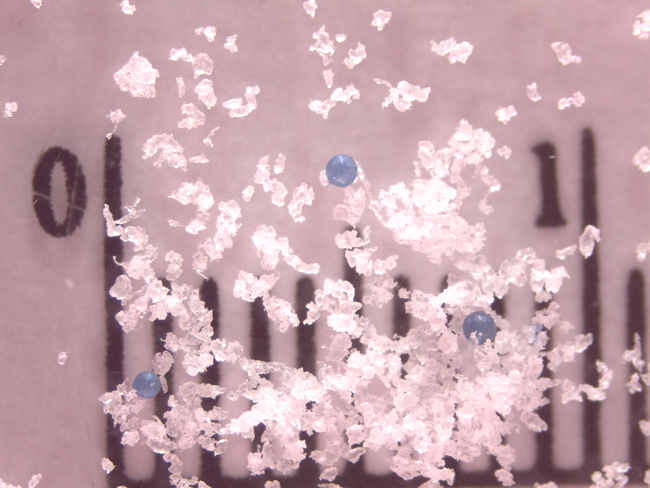

Plastic particles (inset) float within a stream sample like the one Mason took while being interviewed by Al Jazeera America in July 2014. Credit: Nick Gunner; (inset) Sherri Mason

The scientists trawled with a net behind their boat, fishing the plastic bits out of the lake. They then sorted and gathered out the larger fragments using sieves. Analyzing the fragments, they found numerous plastic beads showing atypical peaks, the characteristic signs of plastic degradation.

They also found low levels of silicones and fluorenes. Silicones aren’t known to be especially harmful, but they’re worth studying because, like plastics, they are made from fossil fuel hydrocarbons and also persist in the environment for a long time.(2) Fluorenes are found in compounds such as perfluorinated chemicals (PFCs). These fluorine compounds are very stable and thus persist in the environment, posing a hazard to human health, causing disease of the kidney, liver, and pancreas.(3)

Untraceable

Scientists concede they do not know how the plastics got in the Great Lakes. Did the materials get in at the factory, or after the consumer?

The team couldn’t determine much about the origin of harmful organic compounds that were, in effect, at low levels, attached to the plastic fragments, something beyond the capabilities of the equipment they used and outside the scope of the study.

They do know, however, that microplastics are abundant in the freshwater Great Lakes.

Danger

Researchers collected these plastic microbeads and flakes included within a commercial facewash, using a rinse product and a stainless steel sieve. Credit: Sherri Mason

Plastics may carry harmful pollutants such as PCBs, HOCs, and heavy metals on their surfaces as they are carried by currents, rivers, and streams.

These harmful substances may enter the aquatic food web, and thus into the animal and human food web.

Scientists note being uncertain whether the water they used in the study did not contain some level of plastic contamination from the start, either from plastic storage containers they used, or from the tap itself. They cited a research paper about microplastics having contaminated tap water.

The team reiterated the importance of reducing or eliminating plastic product use from our daily lives.

Mason and her team are still seeking more information about what pollutants might be collecting on the outer edges of these spreading, discarded polymers, and also what those plastics—in our shared waters—might be disintegrating into.

What You Can Do

Consumers can avoid PFCs by avoiding non-stick cookware as well as grease-repellent food packaging like French fry boxes and pizza boxes. Avoid personal care items with the ingredients with the terms “fluoro” or “perfluoro.”(4)

On YouTube: Be The Change

In the video clip above, "Be The Change," two students from the State University of New York (SUNY) at Fredonia introduce us to Mason and, Wigdahl-Perry, among others researching marine debris and microplastics. For more, see: "Tiny organisms in the water eating plastic: Could it harm us all?" and "On YouTube: Plastics - 'We're The Problem, But We're The Solution. Be The Change'"

Footnotes / References

(1) PFOA (perfluorooctanoic acid) and PFOS (perfluorooctane sulfonic acid). Source: CS Mott’s Children’s Hospital, Michigan. https://www.mottchildren.org/posts/your-child/pfas-contamination. Accessed October 16, 2019.

(2) mindbodygreen.com

(3) https://www.mlive.com/news

(4) ibid.

More Info: New York Sea Grant

New York Sea Grant (NYSG), a cooperative program of Cornell University

and the State University of New York (SUNY), is one of 34 university-based

programs under the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s

National Sea Grant College Program.

Since 1971, NYSG has represented a statewide network of integrated

research, education and extension services promoting coastal community

economic vitality, environmental sustainability and citizen awareness

and understanding about the State’s marine and Great Lakes resources.

Through NYSG’s efforts, the combined talents of university scientists

and extension specialists help develop and transfer science-based

information to many coastal user groups—businesses and industries,

federal, state and local government decision-makers and agency managers,

educators, the media and the interested public.

The program maintains Great Lakes offices at Cornell University, SUNY

Buffalo, SUNY Oswego and the Wayne County Cooperative Extension office

in Newark. In the State's marine waters, NYSG has offices at Stony Brook

University in Long Island, Brooklyn College and Cornell Cooperative

Extension in NYC and Kingston in the Hudson Valley.

For updates on Sea Grant activities: www.nyseagrant.org has RSS, Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube links. NYSG offers a free e-list sign up via www.nyseagrant.org/nycoastlines for its flagship publication, NY Coastlines/Currents, which is published quarterly. Our program also produces an occasional e-newsletter,"NOAA Sea Grant's Social Media Review," via its blog, www.nyseagrant.org/blog.