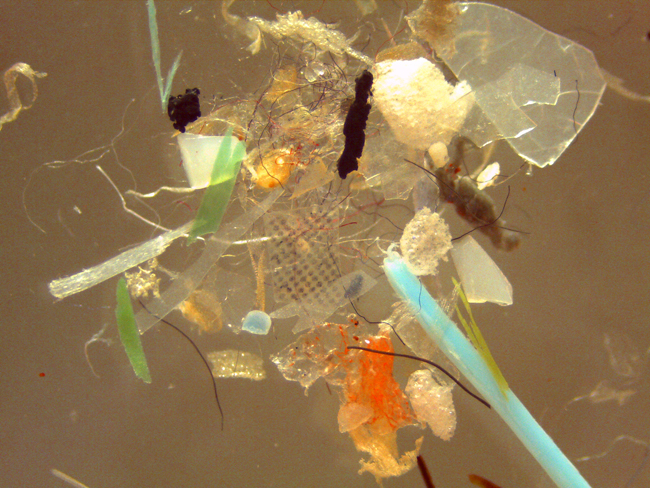

For years people have worried about the environmental impacts from plastics left behind in the oceans and Great Lakes. More recently, though, projects like one funded by New York Sea Grant have brought attention to microplastics, small plastic particles that have found their way into our waterways. Credit: Sherri Mason.

— By Chris Gonzales, Freelance Science Writer, New York Sea Grant

Buffalo, NY, April 19, 2020 – At your local grocery store, you may notice a lot of plastic packaging—but you know better than to eat it. Unfortunately for many animals in the freshwater Great Lakes—a resource for drinking water, trade, and recreation in the Northeast—tiny plastic particles are mistaken for food. Worse, plastics in the food web may transport organic pollutants.

Plastic pollution is a problem in several types of ecosystems, but they are especially a problem in water. Both plastics and organic pollutants contain hydrocarbons, which means pollutants tend to cling to plastics in the water. Scientists are especially concerned about microorganisms such as zooplankton that consume tiny particles of tainted plastic.

“Our New York Sea Grant-funded research demonstrates a critical entry point for microplastics into freshwater systems,” said Courtney Wigdahl-Perry, a biologist at the State University of New York at Fredonia and a researcher on the two-year project, which wrapped up last year. “Zooplankton are a key food source for fish and other invertebrates, so when plastics can hinder their ability to feed, it has major potential implications for the rest of the food web.”

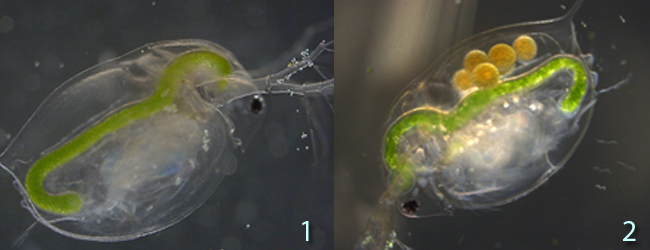

A microscopic zooplankton (1) with microplastics in its gut. A pregnant zooplankton (2) with six eggs above a gut full of microbeads and algae. Credit: Heather Barrett

Small pieces of plastic act as what chemists call “sorbents,” meaning they effectively collect and concentrate persistent organic pollutants (deceptively given the cheerful name POPs). Sherri A. Mason of Penn State Erie, the Behrend College, a chemist, led the project team. She and her group of scientists wanted to study how tiny organisms in the water respond specifically to microbeads, such as the kind found in personal care products, as well as other common refuse plastic found in Lake Ontario. The zooplankton, a microorganism, unwittingly consumed plastic instead of its natural diet. Not only do these violations interfere with normal organism function, the plastics could carry concentrated pollutants, presumably to be conveyed further up the animal food chain.

“While we have learned a lot about the presence of microplastics in the environment—abundance, types, and distribution—we are still early in the process of understanding the ecological consequences of this kind of pollution,” said Wigdahl-Perry.

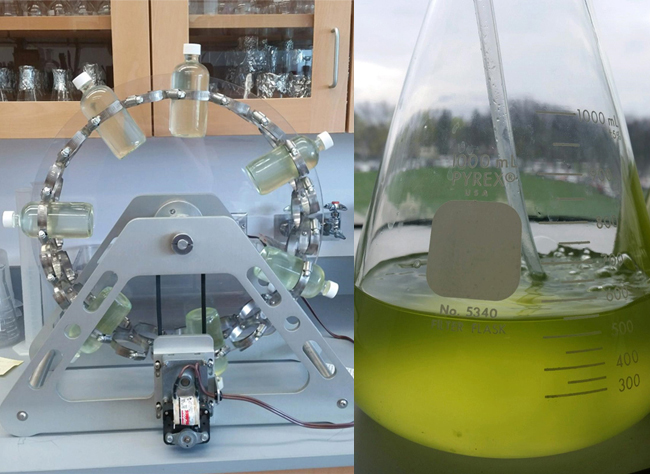

Mason and Wigdahl-Perry, along with Joseph Gardella, a chemist at the University at Buffalo, used a method of filtering and rinsing personal care products in water samples they had taken from Lake Ontario. They set up several experiments in vials containing microorganisms. Some of the tiny waterborne creatures were exposed to various types and sizes of microplastic; others were not.

A device called a grazing wheel (at left) rotates bottles containing zooplankton in water. Zooplankton in the bottles with plastics consumed less algae. This fluid (at right) is a cultured mixture of algae in water, used in feeding experiments. Credit: Heather Barrett

The researchers found that Daphnia zooplankton consumed tiny microbeads. In addition, feeding rates were consistently lower when plastics were present. Zooplankton consume less algae when plastics are a consumable size. Alas, the tiny creatures are evidently consuming less of their natural food source. Zooplankton themselves are a common food source for animals further up the food chain—adult fish, macroinvertebrates, and carnivorous zooplankton.

At the University at Buffalo, Gardella and his graduate student Abigail Snyder studied the surfaces of the microbeads and microplastics collected by Mason from Lake Erie and learned that POPs including Silicones™ and Perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) were adsorbed to the surfaces.

Conclusions

The effects of concentrated and collected POPs being carried along the food chain are not fully understood yet. Nor is the extent of disruptions from microorganisms consuming so much plastic. In future work, the researchers plan to explore this question more fully. In addition, they want to explore a type of plastic referred to as PLGA, which is commonly used for drug delivery in medicine.

Mason hopes to prompt us to ask a bigger question: Knowing as we now do, how do we as a species change our relationship to plastic?

On YouTube: Be The Change

In the video clip above, "Be The Change," two students from the State University of New York (SUNY) at Fredonia introduce us to Mason and, Wigdahl-Perry, among others researching marine debris and microplastics. For more, see: "Plastics floating in the water: What are the risks?" and "On YouTube: Plastics - 'We're The Problem, But We're The Solution. Be The Change'"

More Info: New York Sea Grant

New York Sea Grant (NYSG), a cooperative program of Cornell University

and the State University of New York (SUNY), is one of 34 university-based

programs under the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s

National Sea Grant College Program.

Since 1971, NYSG has represented a statewide network of integrated

research, education and extension services promoting coastal community

economic vitality, environmental sustainability and citizen awareness

and understanding about the State’s marine and Great Lakes resources.

Through NYSG’s efforts, the combined talents of university scientists

and extension specialists help develop and transfer science-based

information to many coastal user groups—businesses and industries,

federal, state and local government decision-makers and agency managers,

educators, the media and the interested public.

The program maintains Great Lakes offices at Cornell University, SUNY

Buffalo, SUNY Oswego and the Wayne County Cooperative Extension office

in Newark. In the State's marine waters, NYSG has offices at Stony Brook

University in Long Island, Brooklyn College and Cornell Cooperative

Extension in NYC and Kingston in the Hudson Valley.

For updates on Sea Grant activities: www.nyseagrant.org has RSS, Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube links. NYSG offers a free e-list sign up via www.nyseagrant.org/nycoastlines for its flagship publication, NY Coastlines/Currents, which is published quarterly. Our program also produces an occasional e-newsletter,"NOAA Sea Grant's Social Media Review," via its blog, www.nyseagrant.org/blog.