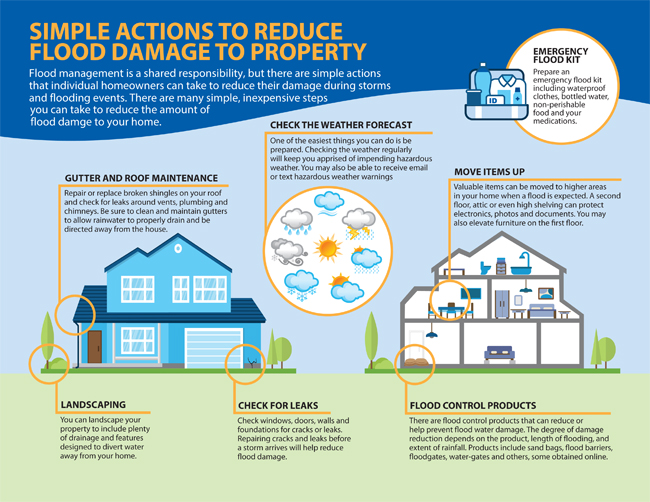

Being resilient before a coastal storm is key, which is why New York Sea Grant has produced a new fact sheet series that starts with "Simple Actions to Reduce Flood Damage to Property" (pdf) and continues with "Options to Reduce Flood Risk to Your Home" (pdf). There are also two companion one-pagers with Resources for Homeowners (pdf) as well as Resources for Municipalities (pdf).

Contacts:

Kathleen Fallon, NYSG Coastal Processes & Hazards Specialist, E: kmf228@cornell.edu, P: 631-632-8730

Babylon, NY, April 9, 2019 - Coastal weather hazards don’t disappear once the Hurricane Season ends. In mid-March, during the height of Nor'easter season, Kathleen Fallon, New York Sea Grant’s (NYSG) Coastal Processes and Hazards Specialist worked with Christie Pfoertner, DOS South Shore Estuary Reserve, and invited experts from the New York Department of State’s Office of Planning Development & Community Infrastructure, The Nature Conservancy, and Hofstra University to share resilience tips with Long Islanders. In the City Hall Board Room, residents of Babylon gathered to learn how to be storm-ready from the end of the winter weather season and beyond.

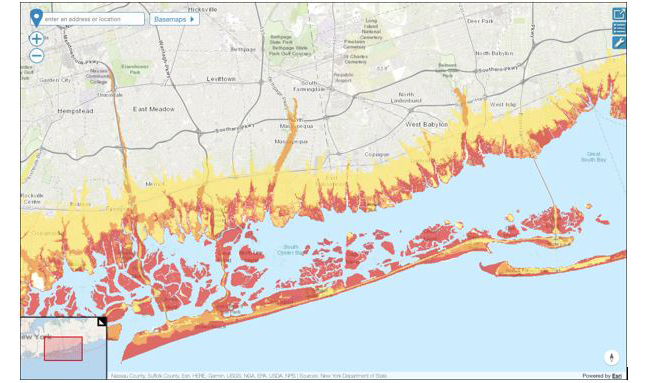

The Town of Babylon is located in the South Shore Estuary, home to about 1.5 million people. Its low elevation makes communities susceptible to flooding during high tide and storms. Credit: Ryan Strother/NYSG.

A gateway map showing current coastal risk areas near Babylon.

Setting the Stage: Risk Management

Carolyn Fraioli, Coastal Resources Specialist, Office of Planning, Development & Community Infrastructure at the NYS Department of State presented on risk assessment and management for homeowners on Long Island.

The New York Department of State uses several factors to evaluate risk, including the hazard, or magnitude and likelihood of a future storm event, exposure, or the local landscape attribute, and vulnerability, or the capacity of an asset to return to service after a storm event. Coastal risk area maps were created to classify risk in order to support planning efforts.

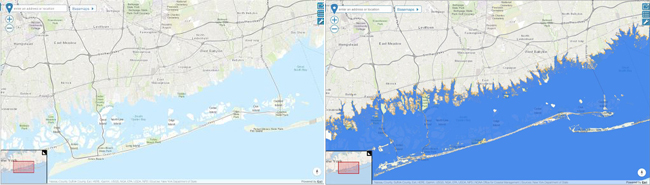

Maps at opdgig.dos.ny.gov, showing current sea level (left) and projections of mean high water inundation near Babylon at six feet of sea level rise (right), a possible scenario estimated for the year 2100.

When it comes to risk management and preparedness, flood risk management is a shared responsibility across various levels of government and individuals. All risk can’t be eliminated entirely, especially when living in a coastal area, but there are several options for risk mitigation. Outreach, natural storage (rain gardens), structural options (bulkheads, seawalls), non-structural (elevating your home), contingency plans, building codes, zoning, and insurance are all essential components of flood risk management.

But, when a storm approaches and accelerates risk, decision making at the individual level happens with or without community planning.

When evaluating acceptable levels of personal risk, it’s important to consider possible courses of action, and calculate which actions are in your best interest considering costs, family member's conditions, and timing. With all of that considered you’ll have more information to decide whether to take action.

“At the end of the day, you’re really deciding on an acceptable level of risk for you and your family,” said Fraioli.

Building Resilience in the Face of a Changing Coast

Dr. Alison Branco, Coastal Director of the Long Island Chapter of the Nature Conservancy discussed the changes coastal residents can expect with sea level rise. In the last century, mean sea levels have risen by a foot in New York. The steady rise of sea levels has recently increased, and “the acceleration of sea level rise is a lot more noticeable in our day to day lives,” said Branco.

“Sunny day” flooding is an expected outcome of sea level rise. Sometimes called “nuisance flooding,” a better term is chronic flooding, which sometimes occurs in coastal areas during high tide because of the moon-tide cycle and not a storm. Flooding like this causes problems for coastal communities. Queens, Hempstead, Babylon, Islip, Brookhaven, and Southampton are areas at highest risk for flood risk. By 2100, nearly 500,000 homes will be at risk in the state of New York, according to data provided by the Union of Concerned Scientists.

Mitigation and adaptation are both vital to resilience in the face of expected sea level rise by up to six feet by 2100. Credit: Ryan Strother/NYSG.

By the year 2100, 21-50 inches of sea level rise are expected, with a worst case scenario of six feet of sea level rise projected. This means that the relative location of coastal ecological infrastructure—namely beaches and marshes—will move significantly.

A mitigation strategy for sea level is embracing dynamic shorelines. Erosion is commonly thought of as a problem requiring a solution, but a better way to conceptualize erosion is as part of a dynamic system. Sand on familiar beaches all came from another location. Alarming as it may seem for beaches to move, sandy shorelines are actually very resilient. Sea level rise won’t get rid of Long Island’s beaches, but if coastal processes are given room they will move to the new shorelines.

So it goes for wetlands. Also very resilient coastal ecosystems, wetlands need room to move. Wetlands can grow vertically, and marsh migration is an expected phenomenon, if room is made. If human infrastructure remains in place and marshes aren’t given room to move, marshes will disappear, according to Branco.

Community is the ultimate driver of flood mitigation efforts, and people are part of the ecosystem on Long Island. “The long term goal as we face sea level rise, is to ensure communities are safe and thriving like how we want wetlands to thrive,” said Branco.

East Coast Winter Storms and Their Many Coastal Impacts

Dr. Jase Bernhardt, Assistant Professor in the Department of Geology, Environment and Sustainability, at Hofstra University shared insights on the impact of winter storms on New York’s Marine District.

East Coast Winter Storms (ECWS) are defined as storms occurring from October to April, most frequently in December, January, February and March. They typically present as closed low-pressure cyclone systems moving towards the Northeast coast. They can strengthen rapidly, and occasionally present as a “bomb” of precipitation when clashing with the Gulf Stream. When strong cold air masses clash with warm air from the south and Caribbean Sea, storm systems can strengthen a bit like a hurricane.

What does all of this look like for coastal communities? Heavy precipitation, freshwater flooding, coastal flooding and beach erosion.

To be prepared for an ECWS, there are three levels of warnings that are important to take note of.

A Winter Weather Warning means that more than six inches of snow and significant impacts from other winter precipitation is likely.

A Winter Storm Watch means that the above conditions are possible in the next 48 hours.

A Winter Weather Advisory means that more than three inches of snow, other types of precipitation are expected.

Rare, but possible for New York, is a Blizzard Warning, which means snow, winds of 35 mph or greater, and less than a quarter mile of visibility. Blizzards are particularly perilous for coastal communities, where several feet of storm surge can also result from the strongest Nor’easter storm system. The track of the storm, proximity to Long Island, speed intensity and track all play key roles in the storm’s impact.

Shoreline Management Options

Fallon and Pfoertner presented possible options for managing shorelines in a sensitive coastal area. When it comes to changing coastlines and homeownership, there are four possible courses of action: you can do nothing, conserve shoreline, raise your property, or relocate all together.

Doing nothing is appropriate if erosion is minimal, risk to structures is minimal, critical habitat and protective features and structures are set back. But, this could have unexpected results, like continued flooding, and possible loss of land.

Choosing to conserve is a low-cost management option that could mean planting grasses to protect dunes, installing fences, and staying on designated paths in sensitive areas. While this is a simple intervention, fences may restrict wildlife access, and dunes do not protect against long-term erosion or inlet migration.

As a more involved management option, raising your property can reduce damage from flood waters and debris. Using flow-through or pile foundations to elevate your home two feet higher than base flood elevation can reduce hazards and flood insurance premiums, but is expensive and requires checking with local zoning codes.

Relocation is the final option. You can reduce your risk of flooding by moving away from a flood zone, participating in a buyout program, and choose not to rebuild homes that are frequently flooded and allow nature to take back the flood-prone area. While this maintains natural processes, and greatly reduces the risk of flooding and erosion, relocating means losing historical ties and community connections in moving to a different area.

Gutter and roof maintenance, checking the weather forecast, and moving items up in your home are all practical ways to reduce potential damage to your property during storms and flooding events. Credit: Ryan Strother/NYSG.

If the best laid shoreline management plans still go awry, there are some things you can do during flooding events to protect your home, family, and property. Move items up in your house, put couches and other hard-to-move furniture on cinder blocks to elevate above the expected flood level. And of course, paying close attention to the weather forecast will ensure you can take preventive measures as early as possible.

Carolyn Fraioli introduces Babylon Residents to online resilience maps and tools. Credit: Ryan Strother/NYSG.

Interactive Community Engagement

The forum wrapped up with demonstrations of a variety of resiliency tools. Fraioli presented the NYS Department of State’s Geographic Information Gateway and Risk Areas Map. Branco, explained how to use the Naturally Resilient Communities Tool. Bernhardt presented a virtual reality tool, which simulates what it might look and sound like to stay in your coastal home during a hurricane. Inside the Virtual Reality headset, wind speeds break living room glass. Rain comes in through the roof of the house, and storm surge floods the living room knee-deep with water.

When deciding whether to stay or go in response to a severe storm, even a short experience in the VR headset may persuade someone to avoid experiencing the perils of storm surge in real life.

Fallon is planning additional NYSG resiliency events on Long Island in the near future, including one on June 12th at the Quogue Wildlife Refuge. Featured in the discussions on improving coastal property resilience are experts from The Nature Conservancy, the NYS Department of State and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)’s National Weather Service. Visit www.facebook.com/nyseagrant or www.twitter.com/nyseagrant for information on upcoming events.

More Info: New York Sea Grant

New York Sea Grant (NYSG), a cooperative program of Cornell University

and the State University of New York (SUNY), is one of 33 university-based

programs under the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s

National Sea Grant College Program.

Since 1971, NYSG has represented a statewide network of integrated

research, education and extension services promoting coastal community

economic vitality, environmental sustainability and citizen awareness

and understanding about the State’s marine and Great Lakes resources.

Through NYSG’s efforts, the combined talents of university scientists

and extension specialists help develop and transfer science-based

information to many coastal user groups—businesses and industries,

federal, state and local government decision-makers and agency managers,

educators, the media and the interested public.

The program maintains Great Lakes offices at Cornell University, SUNY

Buffalo, SUNY Oswego and the Wayne County Cooperative Extension office

in Newark. In the State's marine waters, NYSG has offices at Stony Brook

University in Long Island, Brooklyn College and Cornell Cooperative

Extension in NYC and Kingston in the Hudson Valley.

For updates on Sea Grant activities: www.nyseagrant.org has RSS, Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube links. NYSG offers a free e-list sign up via www.nyseagrant.org/nycoastlines for its flagship publication, NY Coastlines/Currents, which is published quarterly. Our program also produces an occasional e-newsletter,"NOAA Sea Grant's Social Media Review," via its blog, www.nyseagrant.org/blog.