Aerial view of the damage caused by Hurricane Sandy to Casino Pier on the New Jersey coast in October 2012. Credit: U.S. Air Force, Master Sgt. Mark C. Olsen.

— By Chris Gonzales, Freelance Science Writer, New York Sea Grant

New York, New York, March 21, 2019 – Experts are asking us to get our minds into the scenario of what to do should a severe storm come our way.

One such expert, Cara L. Cuite of Rutgers University, helps government officials improve emergency messages about coastal storms. Her studies on how residents respond to different types of warning messages and approaches to evacuation have been funded through, among other sources, the Coastal Storm Awareness Program (CSAP), a $1.8M National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration-funded suite of 10 social science projects administered by Sea Grant programs in New York, New Jersey and Connecticut. CSAP studies including the one Cuite was involved in were conducted to help better understand how people react to storm warnings and make the decision to stay or to go. These community-based investigations ran for 18-months beginning in early 2014 as a result of Superstorm Sandy’s impact on the region in late October 2012.

In her work, Cuite has examined questions such as this one: How do you get people most at risk to evacuate, without provoking “shadow” evacuation, that is, the flight of people at low risk, who thus place unnecessary demands on roads and shelters during an emergency?

She has published journal articles – including “Improving Coastal Storm Evacuation Messages,” which is targeted for emergency managers and was published by the American Meteorological Society’s (AMS) Weather Climate and Society in April 2017 – yet her work is also fascinating for the curious layperson.

“Our team has shed light on the effects of different types of evacuation messages, such as whether evacuations are considered voluntary or mandatory,” said Cuite. “We’ve also explored how different methods of identifying evacuation areas are likely to affect evacuation rates.”

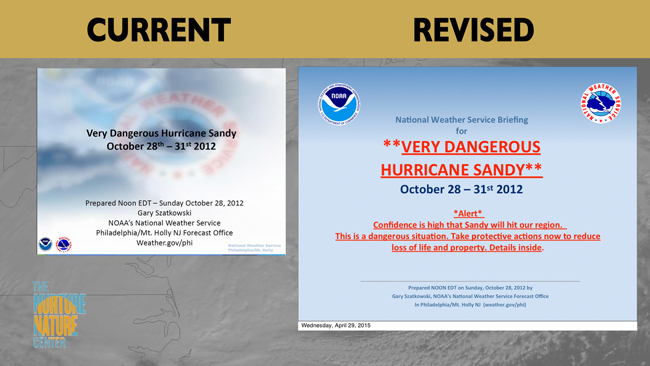

Before and After designs for briefing books produced by the National Weather Service. Credit: Nurture Nature Center.

Her team’s research gives us a sense of some of the challenges emergency managers face. For example, some of them are concerned about wearing the public down with false alarms, analogous to “crying wolf.” Or the fact that many residents are confused about whether they even live in a hurricane evacuation zone. Seventy percent of Connecticut residents who live in a hurricane evacuation zone say they either don’t live, or think they don’t live, in a danger zone. Furthermore, where people live and where they think they live can affect how they respond to warning messages.

After the storm in coastal New Jersey, cleanup was still underway. Credit: Nurture Nature Center.

Future outreach programs could serve to educate people about the risk zones they do or do not live in. Meanwhile, it’s very difficult to target messages to specific geographical areas, as messages travel by social media, word of mouth, traditional media, etc., without regard to flood zone maps.

Some municipalities in the U.S., in fact, are moving toward creating coastal evacuation zones, and Cuite and colleagues call for further research as these become established. Until then, we can hope residents will spend some time putting together their own emergency plans.

“The CSAP has resulted in many recommendations for the public about coastal storms,” said Cuite. “As a result, we are better prepared for the next large storm.”

Rachel Hogan Carr, director of the Nurture Nature Center, studies a report about hurricane risk in her office. Credit: Nurture Nature Center.

A little further inland, another researcher, Rachel Hogan Carr of the Nurture Nature Center in Easton, Pennsylvania, is working on an approach to emergency communication that could be summed up as “right message, right medium, right time, with clear directives.” The U.S. National Weather Service (NWS), which she notes has good predictive tools, has sought advice from her about how to deliver their warning messages optimally.

In her research, she organized five focus groups and led them through a scenario modeled after the seven days leading up to the landfall of 2012’s Sandy. The study took place in Monmouth and Ocean Counties, New Jersey, areas hard-hit by Sandy that are expected to be vulnerable in future storms.

She utilized briefing books produced by the NWS that gave technical information as well as warnings to laypeople about storm dangers.

An official with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) assesses damage in a New Jersey coastal neighborhood after Sandy. Credit: Nurture Nature Center.

Both residents and emergency managers liked the information packages. One resident, for example, mentioned liking the explanatory information that accompanied a graphic. Participants also liked the regional or local perspective of the graphics.

“We found that with careful attention to design and content, the emergency briefings issued by National Weather Service can be an effective tool for sharing forecast information,” said Hogan Carr. “This means including clear, actionable information that helps property owners and residents know how to prepare for impacts. Briefings allow forecasters to relay a tone of urgency about the need to prepare—something that standalone automated graphical products can’t always do.”

A video produced by the Nurture Nature Center describes their work to understand how people assess storm risk, as well as to support the National Weather Service as they optimize their warning messages. More on Nature Nurture Center's "Focus on Floods" project at focusonfloods.org/coastal-flooding. Credit: Nurture Nature Center.

In “Motivating Action under Uncertain Conditions: Enhancing Emergency Briefings during Coastal Storms,” a journal article published in AMS’ Weather Climate and Society in October 2016, Hogan Carr and her colleagues suggest that emergency managers might want to focus on how to translate meteorological details into “statements of meaningful and visible impacts.”

One resident put it this way: “Seventy-five mph [wind]…that’s going to do damage…you have to translate that: Your roof can blow off, secure things.”

An official with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) chats with workers as they contend with a torn-off deck in a coastal area hit by Sandy. Credit: Nurture Nature Center.

Emergency managers often wanted more detail, more information, while residents wanted brief, succinct messages. In short, the emergency briefing packages can be an effective tool for communicating risk to the public, allowing forecasters to give messages a personal tone and a sense of urgency.

“The CSAP has brought to the forefront the importance of understanding not only forecast technology, but the recipients of that technology—the very people who will receive information and need to act,” said Hogan Carr. “Through social science studies of how people understand risk, and what approaches will most help to motivate them to take protective actions, CSAP adds tremendous value to the suite of technological forecast capabilities already in place, maximizing their impact.”

Workers restore a home that was damaged during Sandy, elevating it with a flow-through foundation. Credit: Nancy Balcom, Connecticut Sea Grant Program, University of Connecticut.

Not only are more frequent storm events causing more frequent coastal flooding, but also more people are living in flood-prone areas.

People can take steps to avoid the risk of damage from flooding, but not everyone takes them. These steps include actions like constructing buildings on stilts, or installing flood vents—openings that allow water to pass through the foundation of a building. In the event preventative steps fail, one option for protecting property value is flood insurance.

In "Plans and Prospects for Coastal Flooding in Four Communities Affected by Sandy," a April 2017 journal article published by Gabrielle Wong-Parodi and colleagues in AMS’ Weather Climate and Society, they found that residents recognize risk and expect flooding to increase, though they underestimate by how much, when compared to expert assessments. Wong-Parodi did the research while at Carnegie Mellon University and is now at Stanford.

“Residents affected by extreme weather events such as Superstorm Sandy are aware of the risks of coastal flooding and are willing to undertake both personal and community actions, if convinced of their effectiveness, regardless of their acceptance of climate change,” said Wong-Parodi. “Those individuals with greater social support tend to report greater tolerance for flood risks and greater confidence in community adaptation measures. The role of personal connections in collective resilience is important, but complex—both keeping people in place and helping them to survive there.”

“In the aftermath of Superstorm Sandy, many people raised concerns about the tremendous loss of life, despite ‘spot-on’ predictions and extensive warnings,” said Nancy Balcom, associate director and program leader, Connecticut Sea Grant Program. “Researchers are trying to understand not only people’s experiences during Sandy, but how risk is communicated, with the aim to recommend ways to improve future warnings.”

This home is in the process of being raised, one-and-a-half years after Sandy. Many people were displaced by the storm. Even for those who were able to rebuild, like the family restoring this home, it took a long time. Many people faced the frustration of filing an insurance claim, maybe getting a payment, and in many cases, finding it wasn’t enough to rebuild. Yet people are rebuilding, perhaps in locations that are still vulnerable. Credit: Gabrielle Wong-Parodi.

Wong-Parodi’s research identified some of the actions residents have been taking to protect their lives and property. Some of these actions are taken individually, such as modifications to privately-owned buildings. Other actions are taken in the community, such as talking with neighbors and local officials about planning and preparedness steps one can take, independently or as a community.

Wong-Parodi and her colleagues conducted both in-depth interviews and structured surveys in the New Jersey’s Monmouth and Ocean counties, also where Hogan Carr’s team did their work.

Researchers spoke both with residents and emergency preparedness experts.

The investigators found that residents saw themselves at risk for flooding, with that risk increasing. As a rule, they expressed attachment to their choice of residence, even though they recognized the risk, and affirmed the kinds of social support—personal assistance, helping hands in time of need—they received in their local communities. Residents also saw themselves as primarily responsible for preparing, by taking preventative or adaptive action.

The investigators found a curious bias among residents who estimated risk in the past, present, and future. While residents tended to overestimate the annual probability of flooding 30 years ago, and correctly estimate that risk today, they tended to underestimate the risk looking 30 years ahead.

One interesting side note might suggest a shared, collective path forward: political ideology was unrelated to any other attitude reported in the study. Republican, Democrat, Independent, etc., did not matter. Acceptance of climate change and the need to adopt mitigation behaviors was even across the board.

“The CSAP has enabled social scientists to explore the impacts of extreme weather events such as Superstorm Sandy on people's lives, and has identified possible solutions for helping people adapt to change and build more resilient communities,” Wong-Parodi added.

More Info: NOAA Sea Grant’s Coastal Storm Awareness Program

VIDEO: NOAA Sea Grant documentary short on coastal storm awareness educates emergency managers, empowers coastal communities. Video also points to resources from NOAA's National Weather Service, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, NYC Office of Emergency Management and more. The 4-1/2 minute trailer for NOAA Sea Grant's Coastal Storm Awareness Program's 23-minute documentary, view-able on YouTube.

AUDIO: Theme Song: "Ask Yourself," Written and performed by Barbara A. Branca

Note: If you don't see the player above, it's because you're using a non-Flash device (eg, iPhone or iPad).

Superstorm Sandy in 2012 triggered a nationwide reassessment of coastal storm preparedness in the United States, including in the heavily impacted tri-state region (New Jersey, New York, Connecticut). Nearly 150 deaths and an estimated $50 billion in property damage were attributed to this storm.

Despite forecasts for the late October 2012 storm, too many coastal residents either failed to fully understand the severity of the storm and the dangerous conditions it would produce, or chose not to evacuate in spite of the serious risks of staying in their homes.

And so, the aim of the NOAA Sea Grant’s Coastal Storm Awareness Program (CSAP) was to help better understand through social science how people react to storm warnings and make the decision to stay or to go.

The suite of 10 studies, which was competitively funded at institutions from Yale University to Mississippi State University via Sandy Supplemental funds appropriated by Congress under the Disaster Relief Appropriations Act of 2013. This national competition drew on the decades of experience within NOAA and Sea Grant as well as the well-earned reputation for credibility and trust of the Sea Grant outreach communities in the tri-state region. By combining Sea Grant’s established relationship within local communities with current social science research, this effort helped to maximize awareness and understanding of the true severity of coastal hazards - even amongst hard to reach, isolated groups within communities.

Through research and outreach, both the quality of available information on coastal storm risks to humans, and understanding of factors influencing decisions by coastal residents in response to storm warnings was improved. Coastal storm communication professionals and emergency managers were the primary target audiences for CSAP outcomes. A Program Steering Committee of stakeholders helped guide the program and review the results.

Sea Grant staff and funded researchers shared results of the social science research at several key venues during this multi-year endeavor. Presentations were given at the Interagency Coordinating Committee on Hurricanes annual meeting in Fort Worth TX, at the National Hurricane Conference in New Orleans LA, at the NOAA National Hurricane Center in Miami, and at the Governor’s Hurricane Conference in West Palm Beach FL. Key audience members were local, state and federal officials involved in storm predictions, risk communication, storm preparation and emergency management and response. Numerous requests for additional information were met.

Research findings and related outreach efforts are detailed in a May 2016 comprehensive summary, "NOAA Sea Grant Coastal Storm Awareness Program Comes Ashore." Additionally, you can find a visual wrap-up of this research suite via a 23-minute short documentary and its companion four-and-a-half minute video trailer, which were also released that spring. Both point to resources from NOAA's National Weather Service, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, NYC Office of Emergency Management and more.

For more on NOAA Sea Grant's Coastal Storm Awareness Program see www.nyseagrant.org/csap. NYSG also offers additional resources on severe storms at www.nyseagrant.org/hurricane and www.nyseagrant.org/superstormsandy.

More Info: New York Sea Grant

New York Sea Grant (NYSG), a cooperative program of Cornell University

and the State University of New York (SUNY), is one of 33 university-based

programs under the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s

National Sea Grant College Program.

Since 1971, NYSG has represented a statewide network of integrated

research, education and extension services promoting coastal community

economic vitality, environmental sustainability and citizen awareness

and understanding about the State’s marine and Great Lakes resources.

Through NYSG’s efforts, the combined talents of university scientists

and extension specialists help develop and transfer science-based

information to many coastal user groups—businesses and industries,

federal, state and local government decision-makers and agency managers,

educators, the media and the interested public.

The program maintains Great Lakes offices at Cornell University, SUNY

Buffalo, SUNY Oswego and the Wayne County Cooperative Extension office

in Newark. In the State's marine waters, NYSG has offices at Stony Brook

University in Long Island, Brooklyn College and Cornell Cooperative

Extension in NYC and Kingston in the Hudson Valley.

For updates on Sea Grant activities: www.nyseagrant.org has RSS, Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube links. NYSG offers a free e-list sign up via www.nyseagrant.org/nycoastlines for its flagship publication, NY Coastlines/Currents, which is published quarterly. Our program also produces an occasional e-newsletter,"NOAA Sea Grant's Social Media Review," via its blog, www.nyseagrant.org/blog.