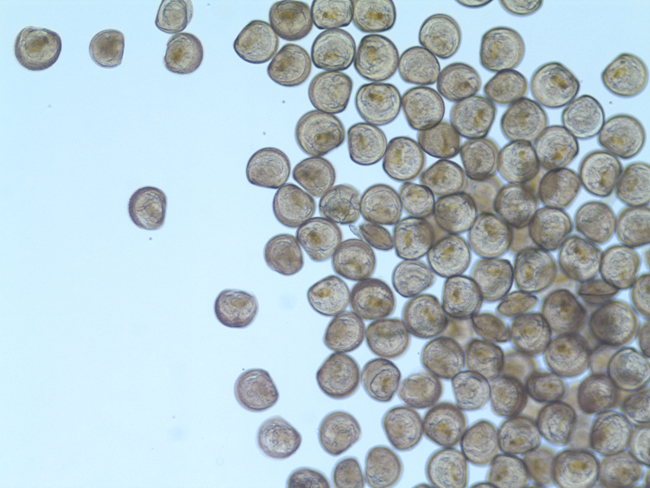

Larval oysters used in the study. Credit: Caroline Schwaner.

— By Chris Gonzales, Freelance Science Writer, New York Sea Grant

Stony Brook, NY, May 24, 2021 - Ocean acidification (OA) is a problem that makes it harder for shellfish such as clams, oysters, and mussels to survive. For example, shellfish grown under harsh OA conditions have a harder time forming shell material, making them more vulnerable to predators. Even if these bivalves can stay alive, it comes with a physiological cost, one we are only now beginning to understand.

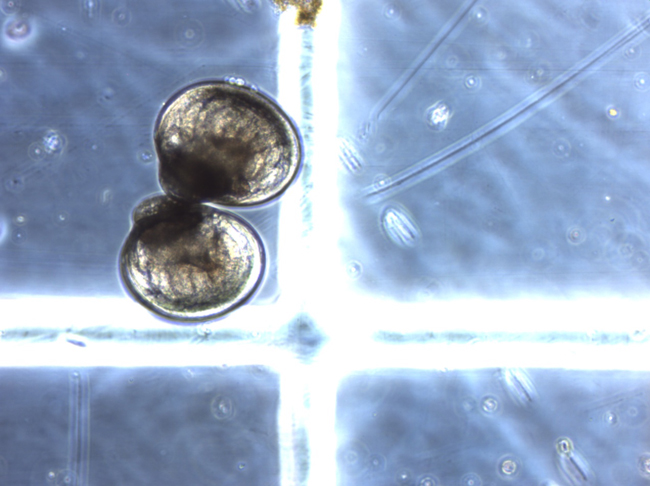

Scientists have recently developed a study to explore the physiological cost of resilience to acidification in the hard clam (Mercenaria mercenaria) and the eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica). Along the way, they identified genes and variants that appear to be important for organisms to develop resilience to acidified seawater.

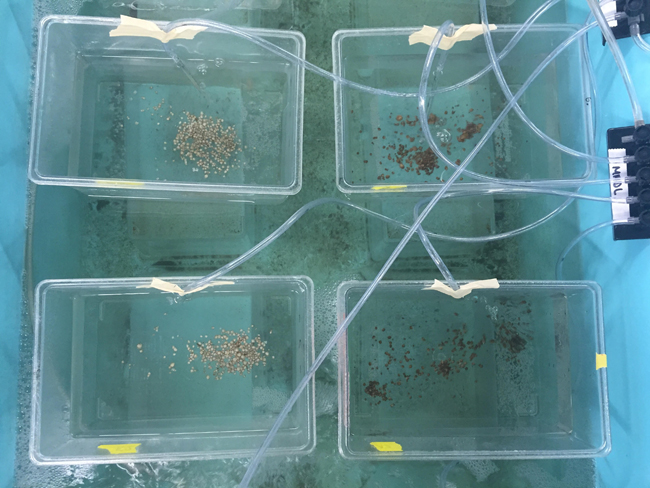

Juvenile clams in OA and normal conditions. The normal have a darker shell. Credit: Michelle Barbosa.

An Inconvenient Cost

“The overarching goal of this work is to better understand resilience to OA in the eastern oyster and hard clam,” said Caroline Schwaner, a Sea Grant fellow at Stony Brook University's (SBU) School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences (SoMAS), who worked on this project.

The research was headed by Bassem Allam, also of SBU SoMAS, and funded by New York Sea Grant.

“In our study, we’re especially taking into consideration the mechanisms of resilience and their associated physiological costs,” said Schwaner.

The effects of OA on bivalves remains unpredictable. The organisms raised in OA conditions tend to be smaller and are more susceptible to bacterial infections as their own immune responses are reduced. This is especially true for larvae and juvenile bivalves.

There are major physiological costs to survival under OA conditions. Increased carbon dioxide in the ocean will result in immunocompromised larvae and juveniles.

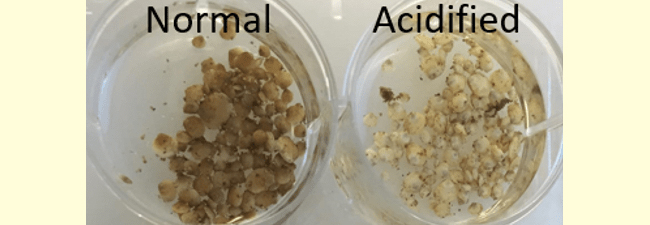

“While we did find species-specific responses (such as contrasting growth trends), we found many similarities between both of these bivalves, including an increased susceptibility to bacterial infection and negative impacts on shell formation,” said Schwaner. “We also sought to understand potential mechanisms of resilience. These included both physiological and molecular mechanisms, from alterations in energy to regulation of gene expression.”

Comparison between juvenile hard clams that were reared in normal versus acidified seawater and the resulting color change that occurred under OA. Credit: Marine Animal Disease Laboratory, Stony Brook University.

Detective Work

The team set out to identify genes and the shellfish organism’s responses—on the molecular level—to OA.

“We demonstrated that there was evident genetic variation between oysters surviving OA conditions and control bivalves, highlighting their potential for adaptation to future OA,” said Schwaner.

Most consistently regulated genes in OA survival response were those involved in the regulation of shell formation and calcium homeostasis.

This study shows us that while these organisms potentially resist OA, it can leave them vulnerable to bacterial infections due to reduced immunity, as well as reduce their growth. However, genes related to shell formation and calcium transport could be potential markers for OA resilience. This research shows the mechanisms by which these bivalves may adapt and survive in poor OA conditions.

Larval oysters used in the study. Credit: Caroline Schwaner.

For more on this project, see the story "RNA Reveals Numerous Viruses of Marine Mollusks."

Also, there was a second NYSG-funded research project supported in 2016 as part of NOAA’s Ocean Acidification Program. Awarded to Dianna Padilla, the study focused on mussels throughout their life cycles, across multiple generations, to assess their ability to adapt to acidic conditions.

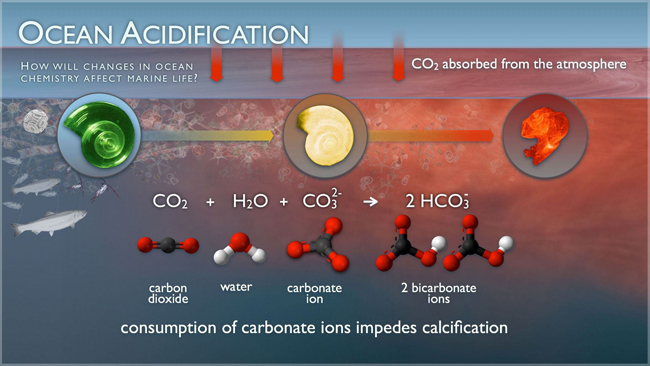

As humans have released carbon dioxide into the atmosphere over the past century, it has led to greenhouse gas accumulation and climate change. At the same time, the oceans have been absorbing about a third of this excess carbon dioxide, leading to a related problem known as ocean acidification (OA), the chemical reactions for which are detailed in the schematic above. The excess carbon in the ocean’s waters leads to heightened levels of acidity, harming marine life. OA is particularly a problem for shellfish such as oysters, clams, and mussels. Credit: NOAA.

More Info: New York Sea Grant

New York Sea Grant (NYSG), a cooperative program of Cornell University

and the State University of New York (SUNY), is one of 34 university-based

programs under the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s

National Sea Grant College Program.

Since 1971, NYSG has represented a statewide network of integrated

research, education and extension services promoting coastal community

economic vitality, environmental sustainability and citizen awareness

and understanding about the State’s marine and Great Lakes resources.

Through NYSG’s efforts, the combined talents of university scientists

and extension specialists help develop and transfer science-based

information to many coastal user groups—businesses and industries,

federal, state and local government decision-makers and agency managers,

educators, the media and the interested public.

The program maintains Great Lakes offices at Cornell University, SUNY

Buffalo, SUNY Oswego and the Wayne County Cooperative Extension office

in Newark. In the State's marine waters, NYSG has offices at Stony Brook

University in Long Island, Brooklyn College and Cornell Cooperative

Extension in NYC and Kingston in the Hudson Valley.

For updates on Sea Grant activities: www.nyseagrant.org has RSS, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube links. NYSG offers a free e-list sign up via www.nyseagrant.org/nycoastlines for its flagship publication, NY Coastlines/Currents, which is published quarterly.