Note: This is a Web extra for news item on PBS's "Protecting New York From Future Superstorms as Sea Levels Rise." Content for this Web extra - filed by reporter Rebecca Jacobson as part of PBS' series, "Coping with Climate Change" - was provided in part by Stony Brook University (SBU) oceanography professor and storm surge expert Dr. Malcolm Bowman and other investigators of SBU's Storm Surge Research Group. As seen below, these researchers detailed for PBS News Hour the four concepts for storm barriers proposed by engineering firms.

For the last decade, New York Sea Grant (NYSG) has provided principal funding to Bowman and SBU's Storm Surge Research Group to work on storm surge science, coastal defense systems and policy issues related to regional protection of New York City and Long Island. The Group was initially formed to develop coastal early warning system for emergency response against flooding in Metropolitan New York.

---

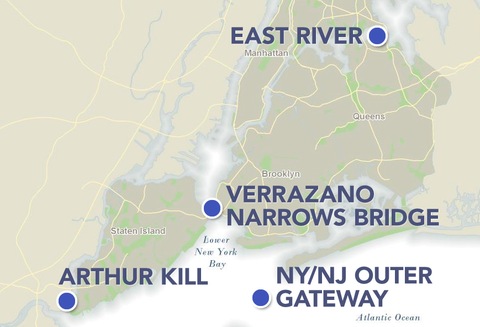

Possible sites for storm surge barriers to protect New York City. The four concepts were presented at an American Society of Civil Engineers conference in 2009.

New York, NY, November 20, 2012 - Superstorm Sandy pummeled New York City, leaving millions without power for days and destroying thousands of homes and businesses along the coast and the New York harbor.

But the lion's share of destruction came from the high storm surge that inundated the city's island boroughs, pushing ocean water into homes and businesses. Insurance claim adjusters and federal agencies are still tallying the cost of the damage, currently estimated at about $33 billion for New York state alone.

Three years ago, four firms proposed four unique designs to answer this very question.

It was at the American Society of Civil Engineers 2009 conference, that four engineering firms -- Parsons Brinckerhoff, ARCADIS, CDM Smith and CH2M (formerly Halcrow) -- were tasked with presenting conceptual designs, each for a specific location. The designs were intended to work together to protect the city against a Category 3 storm.

Here is how some of these designs would operate:

Rolling Gates at the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge (ARCADIS)

Animation by ARCADIS.

The engineering firm ARCADIS presented a rolling gates design just north of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. Under the bridge, the channel is deep, about 70 feet, with swift tides and heavy boat traffic, said ARCADIS engineer Piet Dircke. The $6.5 billion barrier proposed involved several types of gates, which could be closed during a storm to prevent rising storm surge from flooding Manhattan. A pair of curved rolling sector gates would span an 870-foot opening in the center, adjoined by 16 lifting gates with a span of 130 feet, and two lifting gates with a span of 165 feet.

The design would allow water to move through the channel, creating an easy ebb and flow of the tide while letting ships pass through the larger opening.

One word of caution: "A barrier is a safe solution but it's complicated," Dircke said. "There's always a certain impact, always risk of failure, and it's very costly."

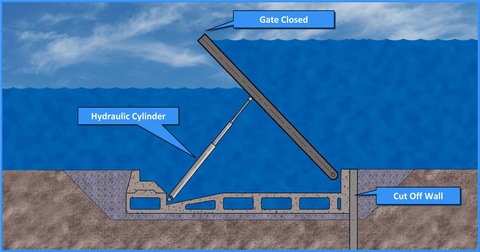

Flap Gates under the East River (Parsons Brinckerhoff)

Image by Parsons Brinckerhoff.

Michael Abrahams, principal engineer at the firm Parsons Brinckerhoff, proposed a flap-type barrier at the upper East River between Throgs Neck and the southern tip of Manhattan island. The barrier consists of a series of panels that normally rest flat on the river floor, but are raised when a surge is expected, creating a wall across the waterway, similar to designs currently in use for Venice. This would allow for the tugboats and barges that frequent the waterway, as well as the local marine life, to pass through completely unobstructed. But the gates would still be high enough to hold against a Category 3 storm surge, Abrahams said.

This type of barrier could be built off-site and then dropped into the river upon completion which would save costs and limit disruptions to traffic along the busy East River, Abrahams said. Overall, he said, the design has minimal impact on the river.

But if this plan were to be implemented, the surrounding neighborhoods would need drainage plans to deal with water flowing over the banks along the sides of the gates, Abrahams said.

Swing Gates and a Bridge at Arthur Kill (CDM Smith)

Animation by CDM Smith.

Larry Murphy of CDM Smith presented the idea for a storm surge barrier on the Arthur Kill, a busy waterway that runs between Staten Island and New Jersey, that relies on tide gates, parallel navigation locks, and a pedestrian drawbridge. Due to its heavy river traffic, he used a design similar to the one designed for the Marina Barrage dam in Singapore in 2008.

This design would actually serve two functions, Murphy said. The tide gates along the bridge could be closed in the event of a storm, stemming the influx of water up the Arthur Kill passageway. The bridge itself would allow pedestrians and cyclists another means of crossing from New Jersey to Staten Island, while drawbridge gates built into the bridge could be raised to allow tugboats, barges and other naval traffic through.

The tide gates would force the flow of the tide, generating enough energy to sustain hydraulic power generators. That could create another sustainable energy source for the region, Murphy said. He estimates that the bridge and gates would cost about $1.5 billion to build, but he believes it would be less expensive than other possible designs to maintain.

While this design is intended to stem the flow of water to lower Manhattan, the barrier could also have saved some of the New Jersey coastline and parts of Staten Island during Superstorm Sandy, Murphy believes.

But, Murphy said, it wouldn't have protected the Rockaways or Coney Island.

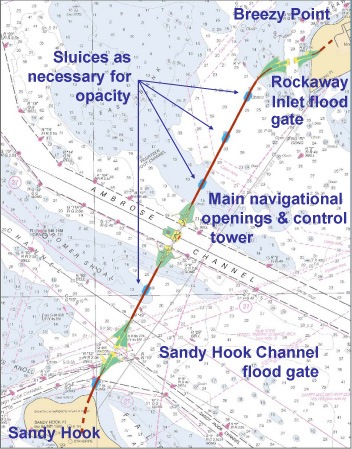

New York to New Jersey Outer Harbor Gateway (CH2M)

Image by CH2M.

The largest of the proposed storm barriers would create a five-mile long causeway with a series of underwater gates that would stretch from the Sandy Hook peninsula in New Jersey to the Rockaways at the mouth of the lower bay. The causeway could cost almost $6 billion for the gates and the five miles of beach dunes and berms at either end of the barrier. In one system, it would do what the designs for the Arthur Kill and the Verrazano-Narrows barriers would do combined.

The gates could be closed when needed to hold floodwater from entering the bay.

The concept leaves room for three major openings in the causeway to let ships and barges through -- one near the Sandy Hook, one near the Rockaways and one over the Ambrose Channel. The Sandy Hook and Rockaways openings would have 300-foot wide lifting gates, flat, solid barriers that would sink into the bay floor to let ships through, but could be raised in the event of a storm. Over the Ambrose Channel are a pair of radius axis sector gates, two pairs of curved gates that swing inwards to protect against flooding.

This design would potentially save the most coastline, but it would also be the largest of all four design concepts.

Right now, these are just concepts. In other words, none of these barrier plans are under official consideration by New York or New Jersey. And they are not without downsides. They are costly and mostly focus on protecting lower Manhattan, not smaller communities like the Rockaways, which was badly damaged during Superstorm Sandy.

And while these barriers could possibly provide complete protection from flooding during a storm, they come with environmental consequences, said Philip Orton, oceanographer at Stevens Institute of Technology. Changing the flow of water into New York estuaries could impact wildlife, a problem already seen today in the harbors. One environmentally-friendly option for dampening the impact of a future hurricane is to rebuild the harbor's salt marshes and oyster beds, which once softened the blow of storms to the islands.

Orton said New York also needs to think about "plugging all the holes" -- in other words, covering subway systems, tunnels, and the city's electrical infrastructure. And changing zoning codes for the area would move some of the at-risk population out of harm's way, he said.

The cost is daunting, Murphy said. Engineers could design a wall around the entire New York harbor, if the city asked for it, but it would be prohibitively expensive, he said.

City planners and officials must decide where and how much to spend on surge protection.

"It's a difficult decision," Murphy said.