New York, NY, September 15, 2012 - With a 520-mile-long coast lined largely by teeming roads and fragile infrastructure, New York City is gingerly facing up to the intertwined threats posed by rising seas and ever-more-severe storm flooding.

So began this past Tuesday's

New York Times feature article, "New York Is Lagging as Seas and Risks Rise, Critics Warn," which examines some of the climate change research being done in Metro NY.

As stated by

New York Times writer Mireya Navarro, "Even as city officials earn high marks for environmental awareness, critics say New York is moving too slowly to address the potential for flooding that could paralyze transportation, cripple the low-lying financial district and temporarily drive hundreds of thousands of people from their homes."

“They lack a sense of urgency about this,” said Douglas Hill, an engineer with Stony Brook University's (SBU)

Storm Surge Research Group. For the last decade, New York Sea Grant has provided principal funding this Group to work on storm surge science, coastal defense systems and policy issues related to regional protection of New York City and Long Island.

SBU Oceanography professor and storm surge expert Malcolm Bowman - also leader of the Research Group - reminds that much of New York's metropolitan area (about 100 square miles) lies just a few feet above sea level and millions of people live close to New York City’s 520 miles of coastline. Therefore, he and the other members of the Research Group warn that New York Metropolitan region is vulnerable to coastal flooding from hurricanes and nor'easters as well as related large-scale damage to city infrastructure, such as hospitals, airports, railroad and subway station entrances, highways, water treatment outfalls and combined sewer outfalls.

"2-3 million people in the outer boroughs of southern Brooklyn and Queens are at risk, with little chance for escape," says Bowman. "During Hurricane Irene last summer, both buses and subways were shut down well before the hurricane made landfall. So how are these people going to evacuate? Walk? Ever tried walking across Brooklyn? High ground is hard to find and a long way from the coast. It's very flat. If the surge makes it over the beaches, look out; it will spread rapidly through the outer boroughs. People are going to try to squash into the upper floors of tenement buildings and get crushed. What about the infants, children and elderly?"

Battery Park after Hurricane Irene, by then a tropical storm, hit a year ago. Low-lying areas of New York City are vulnerable to storms.

Photo Credit: Michael Appleton for The New York Times.

Rather than “planning to be flooded,” as Hill told the

New York Times, city, state and federal agencies should be investing in protection like sea gates that could close during a storm and block a surge from Long Island Sound and the Atlantic Ocean into the East River and New York Harbor.

As cited in a

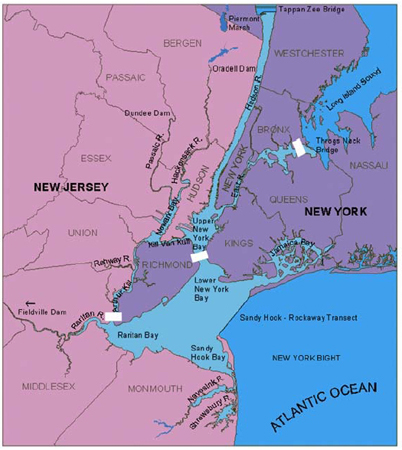

2004 study (pdf), Hill and other members of SBU's Storm Surge Research Group recommended installing movable barriers at the upper end of the East River, near the Throgs Neck Bridge; under the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge; and at the mouth of the Arthur Kill, between Staten Island and New Jersey.

NYSG funded one of the studies with the Research Group, which was summarized in both a Spring 2005

Coastlines article, "Closing the Doors on Storm Surges" (

pdf), as well as a 2007 impact statement, "Could Barriers Protect New York City From Storm Surges?" (

pdf).

During hurricanes and northeasters, closing the barriers would block a huge tide from flooding Manhattan and parts of the Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens, Staten Island and New Jersey, says members of the Research Group.

As explained in NYSG's Spring 2005

Coastlines, the Research Group created a scenario in which a storm generated wind speeds almost double that of September 1999's Hurricane Floyd (downgraded to a tropical storm by the time it reached NY). They dubbed this synthetic storm “Super Floyd.” Such a storm would lead to a peak water level of four feet above mean high tide at the Battery in lower Manhattan, somewhat higher than the three feet peak caused by Floyd.

With such anticipated high water levels, how well would the barriers work? If they had been closed at low tide before the approaching storm, the model predicted that the barriers would have been very effective at the three planned locations. With the barriers closed, water levels on the inside remained at normal levels during the period of the storm.

Bowman says that analogous barriers (those serving a similar function, but having a different structure) have been constructed in New England (Stamford CT, Providence RI, New Bedford MA), the UK (London's Thames River Barrier) and The Netherlands (protecting Amsterdam, Rotterdam). Nearing completion are storm surge barriers in Italy (Venice) and Russia (St Petersburg).

"These structures are, and will be effective, in providing protection against storm surge flooding. In these cases they were built following flooding disasters with loss of life. With careful planning and foresight, such a disaster could be avoided in New York. This project provides the first step.

Now several years later from when these studies were initially conducted, Bowman says that recent research shows that the

Verrazano barrier

location is not optimal. "Much better would be a five-mile levee and

ship

gates system stretching from Far Rockaway to Sandy Hook NJ," he says.

"This could

double as an interstate highway/rail bypass corridor between northern

New Jersey and southern Long Island. The depth of water is much

shallower across the Sandy Hook - Far Rockaway transect than the deep,

narrow Verrazano channel, where strong currents would make it very

difficult to stem the surge flow." Also, Bowman adds, the "outer

barrier" design would protect the 2-3 million people living in the

flood-prone plain of southern Brooklyn and Queens, JFK airport, northern

NJ and southern Staten Island.

According to this past Tuesday's

New York Times article, City officials say that sea barriers are among the options being studied, but others say such gates could interfere with aquatic ecosystems and with the flushing out of pollutants, and may eventually fail as sea levels keep rising. And then there is the cost. Installing barriers for New York could reach nearly $10 billion.

This past February, another NYSG-funded investigation by the Research

Group began. This study examines the combining of storm surge prediction

models from the National Weather Service, universities and technical

institutes. "Since each storm has its own peculiar characteristics and

behavior," said Bowman, "no one model is always the most accurate at

predicting surge events.” The team believes that a forecast obtained by

constructing an ensemble of models will produce the most reliable

predictor of storm event scenarios.

For more on Bowman's discussions on storm surge-related issues in New York City, see the links in the "Related Info" box on this page.

And for more on related projects, search

NYSG's Research Database - You can best find it by searching by Institution (Stony Brook University), or Investigator (Dr. Malcolm J. Bowman or Dr. Douglas Hill).

New York Sea Grant (NYSG), a statewide network of integrated research, education, and extension services promoting the coastal economic vitality, environmental sustainability and citizen awareness about the State’s marine and Great Lakes resources, has been “Bringing Science to the Shore” for over 40 years. NYSG, one of 32 university-based programs under the National Sea Grant College Program of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), is a cooperative program of the State University of New York and Cornell University. The National Sea Grant College Program engages this network of the nation’s top universities in conducting scientific research, education, training, and extension projects designed to foster science-based decisions about the use and conservation of our aquatic resources.

Raised ventilation grates, like these in Lower Manhattan, are intended to deal with flooding in the subway system during severe storms.

Photo Credit: Michael Appleton for The New York Times.

Battery Park after Hurricane Irene, by then a tropical storm, hit a year ago. Low-lying areas of New York City are vulnerable to storms.

Photo Credit: Michael Appleton for The New York Times.