To the casual observer, harmful algal blooms (HABs) first appear as a mysterious, unusual color in the water: red, brown, green, or sometimes blue-green. However, the colorful displays wreak havoc in marine habitats, as blooms can be a nuisance or set off damage in ecosystems. Algae can also make the family dog sick, or cause death, just as it may cause illness or even death in humans. For an ABCs on HABs as well as a snapshot of the 2017 and 2018 snapshot on water quality in Long Island's waters, see "State of the Bays: Water Is at the Core of the Long Island Existence." Credit: Chris Gobler.

—Chris Gonzales, Freelance Science Writer, New York Sea Grant

Stony Brook, NY, September 9, 2019 - Christopher Gobler spent an evening this past spring delivering a carefully-prepared lecture explaining the various urgent challenges affecting Long Island’s water quality. Then, as he outlined numerous efforts underway to protect coastal areas, he repeated, often, “but there is hope.”

Of the initiatives at the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences at Stony Brook University, many are sponsored by New York Sea Grant, which has funded a dozen projects led by Gobler since 2014. The most recent “State of the Bays” lecture, which has become a noted annual event, took place on April 5th.

There is urgency to the topic, Gobler explained, because Long Island’s watersheds make up the region’s sole aquifer—in other words, there is no other source of clean drinking water for the region’s approximately 1.5 million inhabitants—counting Suffolk County, New York alone.

But threats to the aquifer, such as high nitrogen levels, are also a threat to the bays and can lead to harmful algal blooms (HABs), oxygen deprivation, and acidification, as well as higher temperatures due to climate change.

Excessive nitrogen is a key ingredient in more potent (and potentially toxic) algal blooms. The Suffolk County HABs Action Plan calls for, among other things, regulating the use of fertilizers, which SBU researcher Chris Gobler said accounts for 10-12% of nitrogen load into LI waters. For more, see "On YouTube: Sea Grant Leads Suffolk County Effort for Harmful Algal Bloom Mitigation Planning." Credit: Chris Gobler.

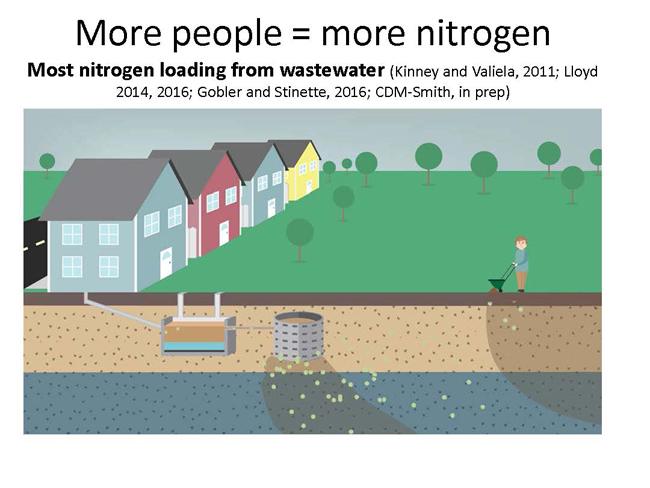

Population and nitrogen explosion

With the region’s population growth in the 20th century has come increased nitrogen levels in the groundwater. Nitrogen-related water-quality issues such as HABs have become more widespread since the mid-1980s.

For example, red tides caused by the Alexandrium dinoflagellate produce saxitoxin, a poisonous molecule one thousand times more potent than cyanide.

“It’s a nitrogen-rich compound,” Gobler explained. “Not only does nitrogen fuel the growth of this organism, but it makes it more toxic.”

Paralytic shellfish poisoning, or PSP, is fatal not only to humans but also to dogs that have eaten contaminated shellfish. The year 2018 saw the fifth closure in seven years of Long Island’s Shinnecock Bay due to the toxic conditions caused by HABs. Fishery closures due to HABs “are becoming an annual occurrence,” Gobler said.

Meanwhile, the Great South Bay has become clearer due to a new inlet, but even so, it has not been immune to brown tides, especially at locations more than ten kilometers away from the new inlet.

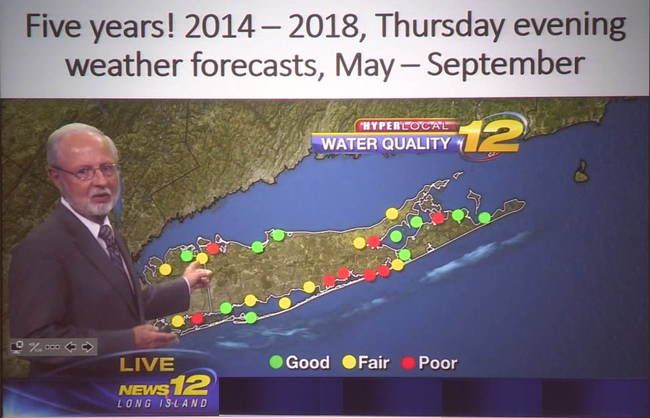

As Gobler shared with Newsday in mid-June, a weekly score card on local waters called the "Long Island Water Quality Index Report" is conducted from Memorial Day to Labor Day by him and his team of more than 20 students and scientists. The prime driver of the project is to provide regular snapshots of ecosystem health, with an eye to how well locations are supporting — or not supporting — robust fishing and shellfishing activity.

Since the water quality project launched in 2014, the team has picked up on how good water quality early in the season tends to morph into poor reports later on. That means we shouldn’t necessarily get too attached to all these good scores so soon in the season, as, over the years, “we've learned that oxygen levels are high and good in June, but declined through July and August, sometimes to levels dangerously low for marine life,” Gobler said.

As seen above in this late August clip, Gobler discussed the issue of HABs at Agawam Park in the village of Southampton, where the lake there resembled pea soup. He said to News 12 Long Island that the algae blooms "can make toxins that are a human health threat. It can also be harmful to animals, specifically pets."

For more information, including additional video clips, see NYSG's early September news item, "In Media, On YouTube: Protect Your Dog From Harmful Algal Blooms."

First nitrogen, now oxygen

Things start to seem even more suffocating when we talk about oxygen, or the lack of it. On the bright side—or perhaps as an indicator of the seriousness of the threat—continuous oxygen monitoring is taking place throughout the Long Island region, done by the Gobler Laboratory’s set of more than 30 sensors across Long Island.

Oxygen deprivation, or hypoxia, can become a problem, for example, as phytoplankton decay, as carbon dioxide is produced and oxygen is consumed.

Gobler talked about widely-publicized fish kills from years past; last year, however, while there were some, and not as extreme, they are still an ongoing issue.

He also expressed concern about climate change, a very real problem, as scientists observe warmer sea temperatures. Since 1982 the planet has warmed about one degree Celsius. This can lead to further consequences of hotter temperatures, such as the rust tide bloom season now being approximately forty days longer. In addition, heavy, intense downpours have seen a 71% increase in the Northeastern United States, more than in any other US region. Scientists, including Gobler, expect nitrogen loading into the sea to increase due to climate change and hypoxia.

Gobler's laboratory provides data that the public can use on continuous water quality monitoring throughout Long Island's waters.

But there is hope, Gobler says

Thanks in part to coordinated governmental efforts, there have been many positive changes. The Long Island region has benefited from a 60% reduction in nitrogen loading into Long Island Sound since 2000. There has also been a reduction of hypoxic areas of the Sound.

Gobler described a project in which nitrogen-reducing wastewater treatment systems are now being tested. The scientists’ goal is to produce a system that will reduce nitrogen release below a threshold of 10 mg/L, cost less than $10,000, and last 30 years. He illustrated several systems, including one that meets two of the performance objectives, but at its current cost of about $25,000 is not quite at the goal.

These include systems such as one called a “permeable reactive barrier” that could remove most nitrogen from the groundwater before it seeps into the bay and out to sea.

Another option to reduce nitrogen harm is modeled after nature’s own inner workings: bivalves, such as hard clams, can improve water quality. Gobler gave an example of growing clams together with seaweeds, in an aquaculture setting, to improve water quality for both. He also showed pictures from a demonstration project where experts are growing “kelp lines,” strands of kelp attached to a submerged rope, aiding water quality throughout the winter months. Kelp removes carbon dioxide, as a natural part of photosynthesis, and releases oxygen. This oxygen helps the clams, which then improve the water quality.

Another promising idea: turn unwanted seaweed into liquid fertilizer, and use it locally for the Long Island region, thus keeping the local nitrogen balance in check, rather than importing tons of nitrogen-based fertilizers onto the island.

(At left) Long Island’s Great South Bay became clearer due to a new inlet, but is not immune to brown tides, especially more than ten kilometers away from the new inlet; Growing “kelp lines,” strands of kelp attached to a submerged rope, throughout the winter months can aid in improving water quality. Credits: Chris Gobler.

In conclusion, Gobler said, mishandling of resources and pollutants has harmed our groundwater. In addition, excessive nitrogen threatens the environment, the health of humans and animals, and our economy. However, nitrogen reductions are leading to significant improvements in certain areas of Long Island. "Continued efforts are needed to restore Long Island's coastal waters," he said. "It's up to us to leave the environment in better shape than when we found it."

More Info: New York Sea Grant

New York Sea Grant (NYSG), a cooperative program of Cornell University

and the State University of New York (SUNY), is one of 33 university-based

programs under the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s

National Sea Grant College Program.

Since 1971, NYSG has represented a statewide network of integrated

research, education and extension services promoting coastal community

economic vitality, environmental sustainability and citizen awareness

and understanding about the State’s marine and Great Lakes resources.

Through NYSG’s efforts, the combined talents of university scientists

and extension specialists help develop and transfer science-based

information to many coastal user groups—businesses and industries,

federal, state and local government decision-makers and agency managers,

educators, the media and the interested public.

The program maintains Great Lakes offices at Cornell University, SUNY

Buffalo, SUNY Oswego and the Wayne County Cooperative Extension office

in Newark. In the State's marine waters, NYSG has offices at Stony Brook

University in Long Island, Brooklyn College and Cornell Cooperative

Extension in NYC and Kingston in the Hudson Valley.

For updates on Sea Grant activities: www.nyseagrant.org has RSS, Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube links. NYSG offers a free e-list sign up via www.nyseagrant.org/nycoastlines for its flagship publication, NY Coastlines/Currents, which is published quarterly. Our program also produces an occasional e-newsletter,"NOAA Sea Grant's Social Media Review," via its blog, www.nyseagrant.org/blog.