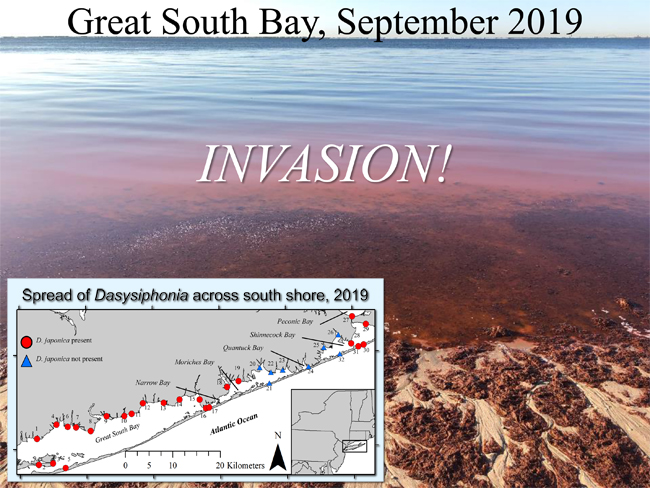

A type of macroalgae, Dasysiphonia japonica, forms in clumps on a beach. As it decays, it releases gases that can irritate the lungs and cause respiratory harm. Credit: Christopher Gobler, SBU SoMAS

—Chris Gonzales, Freelance Science Writer, New York Sea Grant

NOTE: A post-season analysis of Long Island's water quality for 2020 is offered by the Gobler Laboratory in a section at the end of this article.

Stony Brook, NY, August 25, 2020 — A new aggressively-spreading species, Dasysiphonia japonica, a seaweed native to Japan, poses a threat to Long Island shores. Meanwhile, new studies link nitrates in the water to particular health problems.

This according to 2020’s “State of the Bays,” an annual report on the condition of Long Island’s waters. Presented just after Memorial Day, this year’s distinguished lecture was via Zoom (due to COVID-19 precautions) rather than as a traditional gathering at Stony Brook Southampton with community members, graduate and undergraduate students and research technicians from the Gobler Lab.

“Two of the newest findings are that wastewater from septic systems stimulates this aggressive seaweed and high nitrate in drinking water causes negative health effects,” said Dr. Christopher Gobler, a coastal ecologist at Stony Brook University’s (SBU) School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences (SoMAS).

Dasysiphonia seaweed spread in Europe in the 1980s and has been in North American waters for the last decade and a half or so.

“In 2019, we saw a bad outbreak of it spreading on the south shore of Long Island,” said Gobler. “When the seaweed die back, they emit a strong smell of sulfur. But it’s more than a nuisance smell: reports from other countries indicate the gas emitted when it decays can cause health problems including serious lung irritation. Some people affected had to be admitted to hospital intensive care units.”

The spread of this seaweed is propelled by high nitrogen levels.

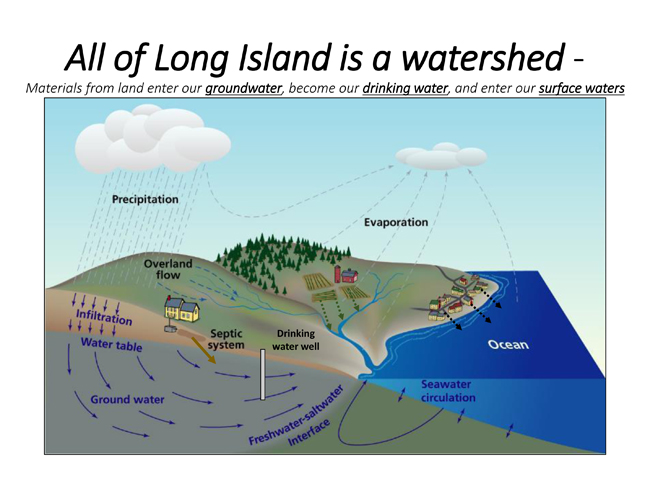

“All of Long Island is a watershed,” said Gobler. “The groundwater is our drinking water. Any activity—agricultural, industrial, household—on land affects our drinking water.”

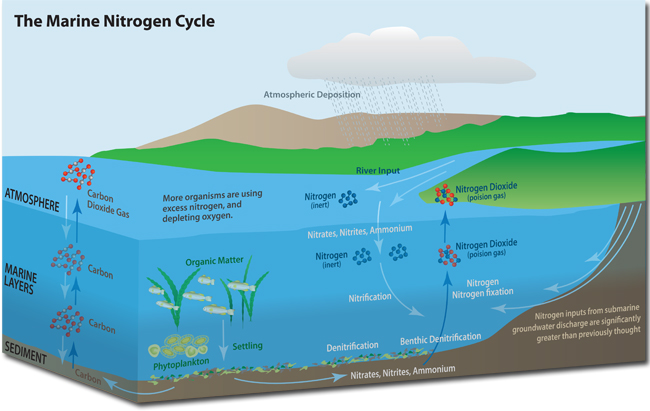

The marine nitrogen cycle: Before nitrogen can serve its vital purpose for plants and animals, it must be fixed via the nitrogen cycle into reactive nitrogen. Nitrogen fixation occurs when microorganisms convert nitrogen gas into usable nitrates. This reactive nitrogen is primarily produced for the agricultural industry and used domestically as fertilizer. When excess reactive nitrogen runs off into waterways, it can cause algal blooms, fish and turtle kills, eutrophication (excess nutrients causing a dense growth of plant life and death of animal life from lack of oxygen) and have impacts for groundwater and threaten the drinking water supply. Credit: Loriann Cody

Nitrate in the groundwater has been increasing. More people living on the land means more nitrogen. Nutrients, such as nitrogen from wastewater emanating from antiquated septic systems that are not designed to remove nitrogen, flow into our coastal waters, leading to harmful algal blooms (HABs), releasing biotoxins that threaten humans, livestock, and even pets. HABs become more intense and more toxic with increased nitrogen.

“HABs have been present in Suffolk County waters at least since the mid-1930s,” said Michael Jensen, principal public health sanitarian at the Suffolk County Department of Health Services. “Their frequency and diversity are increasing. Several marine HABs synthesize biotoxins which can pose serious public health threats while others are ecologically destructive.”

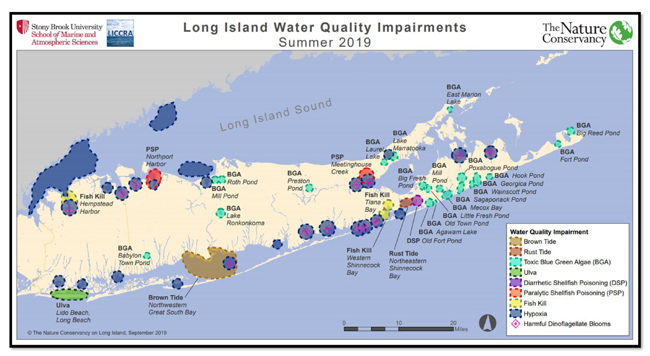

“Meanwhile, we’ve seen mahogany tides across Long Island in May 2020,” continued Gobler.

The alga causing these tides, Prorocentrum minimum, is also propagated by increased nitrogen.

Nitrogen pollution has become a serious, recurring problem in recent years. In an effort to aid the public in warning of HABs, New York Sea Grant (NYSG) and Suffolk County Department of Health Services (SCDoHS) announced the release of the “Suspicious Marine HAB reporting form,” nyseagrant.org/reportHABs. To report suspicious algal blooms in NY’s freshwaters, though, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation asks that the public continue to use on.ny.gov/habform.

There are some key pieces of information being sought when reporting a harmful algal bloom in New York’s marine waters via a new online form. These include: (1) contact information; (2) location of HAB event (you can pinpoint HAB location via an interactive map on the online form); (3) general descriptive information about the HAB; (4) color, odor, incidental fishkills, coverage; (5) uploading photographs is optional. Data collected will be used to: help to guide decisions about monitoring staff deployment, expand the Suffolk County seasonal HAB mapping effort, and move closer to facilitating public access to ‘real time’ information (which was a recommendation in the 2017 Suffolk County HAB Action Plan). Credit: Christopher Gobler, SBU SoMAS

“We are urging anglers, boaters, beach users, and other people who visit the coast to report suspicious algae, such as the new invasive seaweed (see picture) which degrades water quality as it decays, and blooms that are observed in the marine environment, by using the online reporting tool,” said Antoinette Clemetson, fisheries specialist with New York Sea Grant.

“These events have stimulated a need for action to protect our local waters and disseminate information about HABs,” said Jensen. “The information shared in this forum will be useful for all those involved in marine water recreation and establishes a mechanism by which the public can access current information on all marine HABs in Suffolk County and report unusual environmental conditions that might be associated with an emergent HAB.”

Last year, 2019, also saw the demise of the Peconic Bay scallop fishery due to the die-off of adult scallops. Researchers aren’t sure why it collapsed, as algae levels were no different. However, it was the hottest year since 2014, leading to low dissolved oxygen in the water. A parasite of scallops also may have contributed to the die-off. More on Gobler’s related research in “Refuge Areas Could Protect Prized Fisheries in a Changing Climate.”

Gobler covered a series of epidemiological studies by the National Institutes of Health and other organizations during the last decade that have reported an elevated incident of certain forms of cancer with nitrate levels exceeding 3 mg/L in drinking water, a level commonly found in Suffolk County.

The ecologist also highlighted a half-dozen provisionally-approved innovative or advanced onsite wastewater treatment systems that reduce nitrogen in wastewater. He also mentioned nitrogen-removing biofilters that were designed by the New York State Center for Clean Water Technology at Stony Brook University that reduce nitrogen in wastewater to less than 10 mg/L and take out a number of prescription drugs and other substances including personal care products. The lab has gotten the price down on a new residential filter installation to about $20-25K, moving closer to their desired range of $10K.

The ABCs of HABs

To the casual observer, HABs first appear as a mysterious, unusual color in the water: red, brown, green, or sometimes blue-green. However, the colorful displays wreak havoc in marine habitats, as blooms can be a nuisance or set off damage in ecosystems. Algae can also make the family dog sick, or cause death, just as it may cause illness or even death in humans.

While the color gives rise to common names such as red tide or brown tide, scientists use the technical term “HABs” to denote several types of “harmful algal blooms,” which are defined as conditions when a subset of algal species—tiny aquatic plants—produce toxins or grow excessively, harming humans, other animals and the environment.

As murky, algae-filled water washes up on shores, several major types of threats could be present. One class of HABs is harmful to marine life. This includes the microscopic alga Aureococcus anophagefferens, which may bloom in such densities that the water turns dark brown, a condition known as “brown tide.” Brown tides are known for blocking light, knocking down the eel grass that fish and shellfish rely on for habitat.

Another group of HABs on Long Island can cause illnesses such as paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP) if people consume shellfish that have been feeding in the affected area. The most common of these HABs is the dinoflagellate Alexandrium. Some symptoms can range from nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and cramps. In severe cases, people can be afflicted with dizziness, headache, seizures, disorientation, short-term memory loss, respiratory difficulty and even coma.

In Photos, On YouTube: 2020 State of the Bays back to top

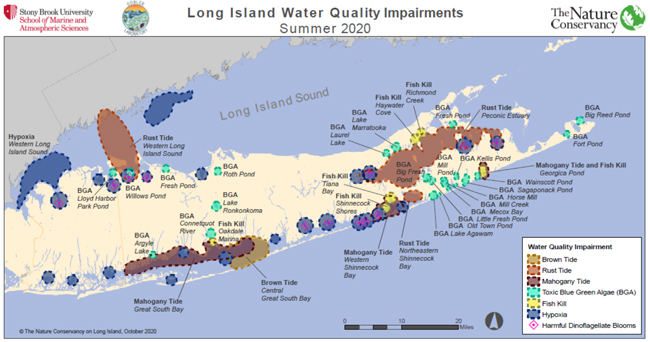

The map above, generated by the Gobler Laboratory, shows precisely where on Long Island various algal blooms and low-oxygen zones developed during the summer of 2020. Events depicted include algal blooms caused by Prorocentrum minimum causing harmful mahogany tides, rust tides caused by the algae Cochlodinium, brown tides caused by Aureococcus, and toxic blue green algae blooms commonly caused by Microcystis. The map also depicts hypoxic or low-oxygen zones which are dangerous to marine life across Long Island Sound and more than two dozen other locations across Long Island. Credit: Chris Gobler, SBU SoMAS

Stony Brook, NY, October 14, 2020 - During the months of June through October, every major bay and estuary across Long Island was afflicted with toxic algae blooms or oxygen starved waters or both. Heavy loads of nitrogen from sewage and fertilizers are the ultimate cause of these disturbing events.

“The summer began, in June, with mahogany and brown tides and ended with a harmful rust tide that continues today across Long Island Sound,” said Dr. Christopher Gobler, Professor of Coastal Ecology and Conservation at Stony Brook University. “In between, a record-setting 24 lakes and ponds across Long Island were afflicted with toxic blue-green algae; oxygen-depleted waters found at more than two dozen locations from Great Neck to East Hampton; and fish kills occurred across another half-dozen sites. The confluence of all of these events in all these places across all of Long Island in a single season is a troubling occurrence.”

The widespread nature of dead (hypoxic) zones (regions of low or no dissolved oxygen) across Long Island is of particular concern, as they threaten the health of fish. Equally alarming was the large number of water bodies with toxic blue-green algal blooms. For the past five years, Suffolk County has had more lakes with blue-green algal blooms than any other of the 64 counties in New York State, a distinction that is likely to be repeated in 2020. Blue-green algae make toxins that can be harmful to humans and animals and have been linked to dog illnesses and a dog death on Long Island.

Almost all of these events can be traced back to rising levels of nitrogen coming from household sewage that seeps into groundwater and, ultimately, into bays, harbors, and estuaries.

To the casual observer, harmful algal blooms (HABs) first appear as a mysterious, unusual color in the water: red, brown, green, or sometimes blue-green. However, the colorful displays wreak havoc in marine habitats, as blooms can be a nuisance or set off damage in ecosystems. Algae can also make the family dog sick, or cause death, just as it may cause illness or even death in humans. For an ABCs on HABs as well as a snapshot of the 2018 and 2019 snapshot on water quality in Long Island's waters, see "State of the Bays: "But There Is Hope." Credit: Chris Gobler, SBU SoMAS

A weekly scorecard on local waters called the "Long Island Water Quality Index Report" is conducted from Memorial Day to Labor Day by Dr. Chris Gobler and his team of students and scientists. The prime driver of the project is to provide regular snapshots of ecosystem health, with an eye to how well locations are supporting — or not supporting — robust fishing and shellfishing activity.

Since the water quality project launched in 2014, the team has picked up on how good water quality early in the season tends to morph into poor reports later on. That means we shouldn’t necessarily get too attached to all these good scores so soon in the season, as, over the years, “we've learned that oxygen levels are high and good in June, but declined through July and August, sometimes to levels dangerously low for marine life,” Gobler said.

Algae blooms "can make toxins that are a human health threat. It can also be harmful to animals, specifically pets," says SBU SoMAS' Dr. Chris Gobler. For more information, including additional video clips, see NYSG's early September news item, "In Media, On YouTube: Protect Your Dog From Harmful Algal Blooms."

All of Long Island is a watershed. Materials from land enter our groundwater, become our drinking water, and enter our surface waters. Credit: Christopher Gobler, SBU SoMAS; Jack Cook/WHOI.

All of Long Island is a watershed. Materials from land enter our groundwater, become our drinking water, and enter our surface waters. Credit: Christopher Gobler, SBU SoMAS; Jack Cook/WHOI.

More Info: New York Sea Grant

New York Sea Grant (NYSG), a cooperative program of Cornell University

and the State University of New York (SUNY), is one of 34 university-based

programs under the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s

National Sea Grant College Program.

Since 1971, NYSG has represented a statewide network of integrated

research, education and extension services promoting coastal community

economic vitality, environmental sustainability and citizen awareness

and understanding about the State’s marine and Great Lakes resources.

Through NYSG’s efforts, the combined talents of university scientists

and extension specialists help develop and transfer science-based

information to many coastal user groups—businesses and industries,

federal, state and local government decision-makers and agency managers,

educators, the media and the interested public.

The program maintains Great Lakes offices at Cornell University, University at Buffalo, SUNY Oswego and the Wayne County Cooperative Extension office

in Newark. In the State's marine waters, NYSG has offices at Stony Brook

University in Long Island, Brooklyn College and Cornell Cooperative

Extension in NYC and Kingston in the Hudson Valley.

For updates on Sea Grant activities: www.nyseagrant.org has RSS, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube links. NYSG offers a free e-list sign up via www.nyseagrant.org/nycoastlines for its flagship publication, NY Coastlines/Currents, which is published quarterly. Our program also produces an occasional e-newsletter,"NOAA Sea Grant's Social Media Review," via its blog, www.nyseagrant.org/blog.