Graduate student Tyler Abruzzo and research technician Josh Zacharias picking through a heavily-vegetated trawl during a field sample. Credit: Michael Frisk

— By Barbara A. Branca

Stony Brook, NY, January 10, 2017 - When Superstorm Sandy tore a breach in the barrier island that protects Long Island’s Great South Bay, how was the Bay’s ecosystem affected? This complex question was answered in part by a NYSG research project: “Effects of a storm-induced barrier breach on community assemblages and ecosystem structure within a temperate lagoonal estuary.”

The interdisciplinary research team, led by Michael Frisk of Stony Brook University’s School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences (SoMAS), included invertebrate scientists Robert Cerrato (SoMAS) and Matthew Sclafani (Cornell University Cooperative Extension), fisheries biologist, Janet Nye (SoMAS), coastal engineer Charles Flagg (SoMAS), finfish specialist Skylar Sagarese (The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Marine Fisheries Service) and SBU post-doctoral researcher Jill Olin.

The funding from New York Sea Grant supported the spring, summer and fall field surveys conducted during 2013, the year following Sandy, and made comparisons with pre-Sandy surveys conducted by the NYSDEC in 2007. This 2013 trawl determined the spatial distribution and habitat preferences (salinity and temperature) of finfish and invertebrate species over a region stretching from Fire Island Inlet in the western portion of Great South Bay to Bellport Bay in the eastern portion of the Bay. In 2014 similar surveys were funded by NYSDEC and in 2015 by the National Park Service.

Says post-doc Olin, “The biggest challenge in coordinating this research was being ready to sample the Great South Bay just six months after Sandy…this was a huge effort and really required all scientists to pitch in to go out in the field and perform the trawl survey. That first year we really had to drop everything and make it happen. We were lucky that we had the necessary gear and expertise to conduct those first surveys.”

During a field sample, (left photo) researcher Janet Nye and graduate student Irvin Huang clean the otter trawl net. (right photo) Graduate student Kellie McCartin holds a spiny dogfish. Credit: Michael Frisk

Uptick in salinity brings on species shift

The migration of the breach in Fire Island caused by the superstorm in late 2012 has been captured in a series of dramatic flyover photographs made by Charlie Flagg of SoMAS. [Go to SoMAS links of the migration of the breach wherever logical.] Over time, the biggest change in the chemistry of Great South Bay following the breach was an increase in salinity. Researchers observed that in 2015 salinity was on average about 4 parts per thousand higher than it was in 2007.

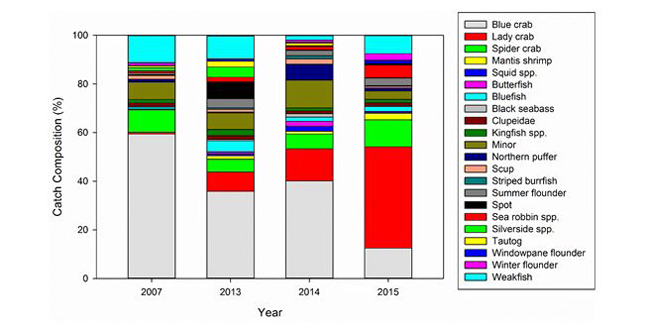

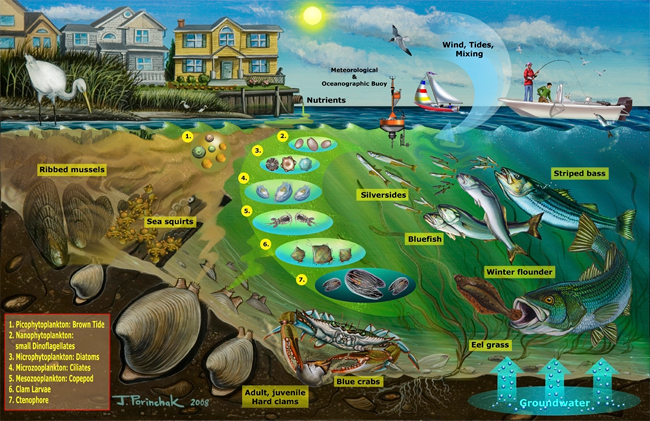

From a biological perspective there was a clear increase in the overall number of species collected in trawl surveys of Great South Bay following the breach. The research team’s collection efforts over time have been summarized in the grid below. The numbers show a shift in the dominant species. Most noticeably within the invertebrate assemblage, blue crabs have been replaced by lady crabs. Finfish populations show changes and even the marine mammal population changed as pennipeds (members of the seal family) have been spotted in the Bay

since the breach.

The biggest change in Great South Bay following the breach has been a shift in salinity. From a biological perspective, Frisk and his team of researchers observed that there is a clear increase in the number of species collected in their trawl surveys in the years following the breach. Also, there is a shift in the dominant species collected in each following the breach, as seen in the "Species composition in Great South Bay" figure above. The most notable change has been the decrease in blue crab abundance and increase in lady crab abundance. Credit: Jill Olin

A 120 year history of ecosystem structure and maturity of Great South Bay, New York. Credit: Nuttall, M.A, A. Jordaan, R.M. Cerrato, M.G. Frisk

Old Inlet Bay, as seen in a flyover on August 5, 2016 Credit: Michael Frisk

The breach influences algal blooms

Pertinent to the biological changes, Flagg’s aerial photos have been used to identify recent changes in the algal component of the ecosystem. According to Flagg, the chlorophyll records for 2015 and 2016 are quite different. In 2015 there was a short-lived brown tide bloom starting in early June, which gave way in Bellport Bay to a stronger and longer lasting endemic green algal bloom that gradually tapered off by September. But 2016 brought on a different story. There was a very intense but short-lived mahogany algal bloom in May, after which the waters in the Bay were clear until July when a lesser green algal bloom started. Although the cause for the differences between the years is not clear at this time, the winter of 2016 was noticeably warmer through March than the previous year. This plus the relatively dry spring and summer, which probably reduced the supply of nutrients from streams and ground water, may have set conditions against the brown tide and allowed the mahogany algae to flourish.

With changes in salinity, temperature, algal bloom trends, invertebrate and vertebrate species, there has been a richness of biodiversity introduced to the ecosystem. After the 2016 data sets are analyzed, the Frisk Lab will prepare a complete report on the storm-induced effects on the ecosystem of Great South Bay.

More Info: New York Sea Grant

New York Sea Grant (NYSG), a cooperative program of Cornell University

and the State University of New York, is one of 33 university-based

programs under the National Sea Grant College Program (NSGCP) of the

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The NSGCP

engages this network of the nation’s top universities in conducting

scientific research, education, training and extension projects designed

to foster science-based decisions about the use and conservation of our

aquatic resources. Through its statewide network of integrated

services, NYSG has been promoting coastal vitality, environmental

sustainability, and citizen awareness about the State’s marine and Great

Lakes resources since 1971.

New York Sea Grant maintains Great Lakes offices at SUNY Buffalo, the

Wayne County Cooperative Extension office in Newark and at SUNY Oswego.

In the State's marine waters, NYSG has offices at Stony Brook University

and Stony Brook Manhattan, in the Hudson Valley through Cooperative

Extension in Kingston and at Brooklyn College.

For updates on Sea Grant activities: www.nyseagrant.org has RSS, Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube links. NYSG produces a monthly e-newsletter, "NOAA Sea Grant's Social Media Review," via its blog, www.nyseagrant.org/blog. Our program also offers a free e-list sign up via www.nyseagrant.org/coastlines for its flagship publication, NY Coastlines/Currents, which is published 1-2 times a year.