— By Chris Gonzales, Freelance Science Writer, New York Sea Grant

New York, NY, December 23, 2020 - New York City coastal waters once were the center of a booming oyster fishery. Our native eastern oysters (Crassostrea virginica) were once so abundant they were dredged, canned, and shipped by steamboat around the world. But now we have almost none.

In a November 2018 PLoS ONE journal article1, Katherine McFarland and coauthors investigated an extensive surviving population of the oyster that was recently found in the Hudson/Raritan Estuary (HRE)—a system of bays and waterways where coastal rivers meet the ocean—near Tarrytown, NY. Their findings about the robustness of this population have big implications for ecological restoration efforts.

The reefs of the eastern oyster provide habitat for many other species and its filter feeding clarifies the water. Thus this bivalve plays a key role in the ecology of coastal waters.

The study cited in the journal article was funded in part by New York Sea Grant (NYSG) and led by article co-author Matthew Hare, an ecological geneticist at Cornell University.

In the investigation, Hare and his colleagues produced oysters in a hatchery from wild broodstock—adult oysters, 2-3 years old, used to make baby oysters—then placed them in experimental cages in multiple parts of the estuary. Over two years McFarland monitored the growth, survival, and body condition of the oysters, and compared them across diverse environments. Their study sites included locations in Jamaica Bay, New York City Harbor, the East River northeast of Manhattan, and further north in the vicinity of the Governor Mario M. Cuomo Bridge (near the former Tappan Zee Bridge).

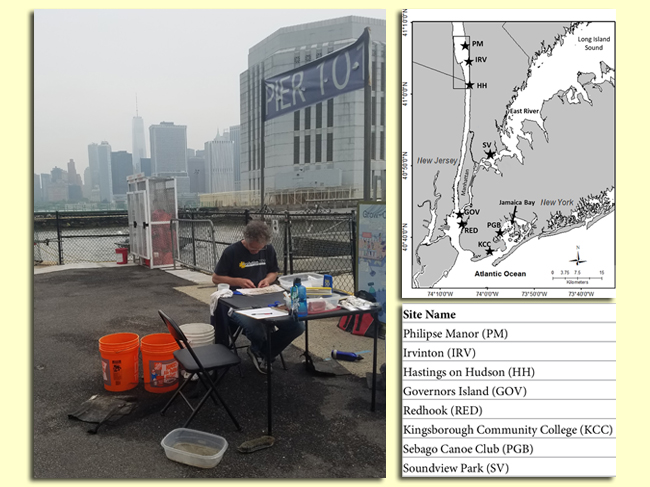

(At left) Matt Hare counts spat at the Governor's Island field site. You can see just how close the team is to the southern tip of Manhattan, with a view of the World Trade Center in the background; (At right) A map of the study’s sample site areas (including around Governor's Island) within the Hudson/Raritan Estuary. Credit: Katherine McFarland, NOAA Federal.

Scientists knew that the HRE might have sites with a range of suitability for oyster growth and survival and wanted to understand this diversity better. Knowledge of heterogeneity in the HRE would be important for restoration planning. Furthermore, the discovery of the Tappan Zee–Haverstraw Bay (TZ-HB) population, which they believe might be capable of reseeding other parts of the estuary, is motivating further studies.

“Restoration of the oyster—this keystone species—is motivated by a desire to bring ecological functionality back to degraded habitats,” said Hare.

Protect shorelines

Estuaries provide essential habitat to hundreds of species, and it’s likely that humans choose to settle in these places—think coastal cities—because of their rich natural resources.

Some scientists are now saying we have a responsibility to restore and protect these coastal estuaries because of the significant impact large human cities are having on them.

These ecosystems are fragile to begin with, yet humans continue to “harden” the shorelines with human-made structures in order to control the river.

Enter the oyster, a creature that can play an outsized role in shoreline restoration. These creatures not only clarify the water by filtering out microalgae for food, they protect shorelines, making them more resilient. Specifically, Hare says, the three-dimensional reef structure of oyster beds can dissipate energy in a storm surge, the rise of water driven toward shore by storm winds, over and above predicted tide levels.

“Yet restoring ecological function to degraded habitats is extremely challenging. Doing so meaningfully, and sustainably, in an urban estuary is like using our experience gained from going to the moon to plan a trip to Mars,” said Hare.

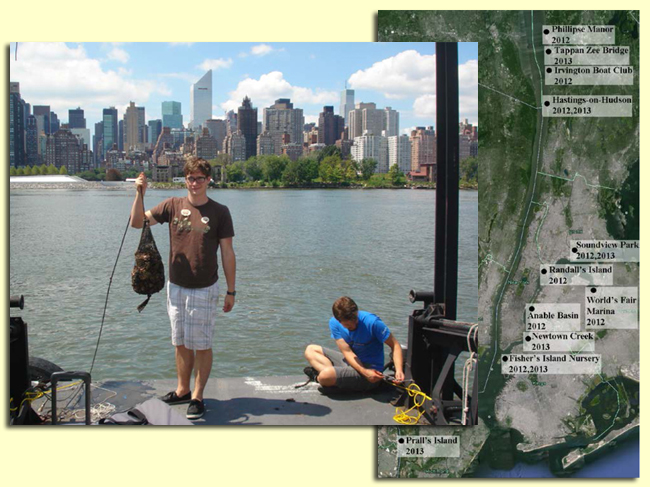

Matt Hare and Harmony Borchardt-Wier anchoring a cage of experimental oysters at the Soundview site, East River, NYC in 2012. Credit: Sarah Crestol.

Perfect homes

For oyster restoration efforts to be successful, scientists need to know how to prioritize—where to concentrate their efforts for maximum restoration efficacy. Once suitable intervention locations are chosen, there’s the weather: changes in precipitation and warming water temperatures. Also, there’s the urbanization of coastlines, which can bring about changes in salinity, spread disease, and disrupt habitat connectivity. Meanwhile, devastating diseases of shellfish are expanding their range.

Scientists may not be able to find the perfect “fixed habitat,” but rather find habitats with beneficial ranges of variability—ideal variations in salinity and temperature, for example.

“Since baby oysters disperse from their home reef, a restoration strategy that includes multiple sites within an estuary provides the greatest chance for success,” said Hare.

This study measured various HRE habitats at seven monitoring sites, in terms of temperature, salinity, and depth. At four of the sites, they measured dissolved oxygen.

The researchers wanted to know if experimental oysters would struggle more to survive or grow in areas with high-density human presence—likely associated with, for example, greater pollution, or water turbulence from boat wakes. Or would the experimental oysters generally fare well everywhere, showing broad flexibility and resilience?

“Our study contributes basic information on oyster survival, growth, reproduction and disease across the potentially suitable habitats in the Hudson River Estuary,” said Hare. “Interestingly, less disturbed estuaries typically have the highest oyster population density and strongest average oyster performance in the middle, moderate salinities zone, and show diminishing survivorship or growth near fresh water at the top of the estuary and oceanic water near the bottom.” In the HRE it is the middle zone where human population density is highest.

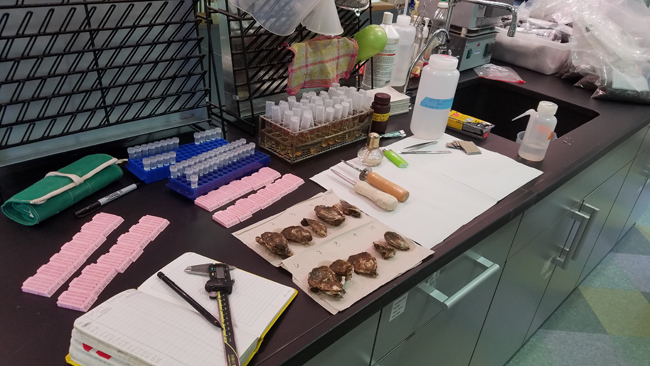

Each individual oyster was measured using calipers (length, width, height) before being dissected. Tissue sections were cut for histological analysis (pink cassettes), sampled for dermo disease analysis (tall tubes), and a tissue section archived for genetic analysis (small tubes in blue racks). Credit: Katherine McFarland, NOAA Federal.

Hero cousins

The study ran from late August 2015 until August 2017. At the end of each phase of the research, some of the oysters from each of the seven sites were sacrificed in order to measure their overall body condition. A second sample was taken, and again sacrificed, to measure the presence of P. marinus, the pathogen that causes a common ailment of oysters called dermo disease. A third sample was taken to assess reproductive maturity at two years of age.

After analyzing their results, Hare is optimistic about the suitability of this urban estuary for oyster restoration. He also believes, as shown through further studies, that the Tappan Zee–Haverstraw Bay remnant wild oysters in particular are a potential “super-hero” population that could be leveraged to restore the rest of the estuary.

Scientists, including Hare, caution that not every habitat can be restored. However, this wild TZ-HB population can do well in both low and moderate salinity conditions, a promising sign.

Undergraduate interns are hard at work measuring growth of oyster spat at the Sebago Canoe Club field site in Brooklyn, NY. From left to right: Nicole Tu-Maung, Adam High, and Cory Snyder. Credit: Katherine McFarland, NOAA Federal.

Comeback hopes

To quickly promote population recovery of oysters in the HRE, one could follow two strategies: (1) improve habitat and (2) seed restored habitat with wild transplants or hatchery-produced oysters or their young.

Scientists believe high genetic diversity of these populations would be necessary to enable such oyster comebacks, because with a more diverse genetic “hand of cards,” so to speak, the better the chances of adapting through natural selection to climate change.

Yet restoration efforts to date routinely use oysters of similar genetic stock, mostly from hatcheries.

The authors believe their work lays the groundwork for future studies, which can provide compelling quantitative data on the phenotypic and population fitness effects when oysters habituated and maybe even adapted to one environment, like low salinity, are placed in a very distinct environment. This is an unconventional approach to restoration, but could promote maintenance of native genetic diversity.

Other restoration constraints may include vulnerabilities experienced by the larval dispersal stage of oysters. For restoration to be sustainable the environment needs to support every part of the oyster life cycle. “Even if growth and survival of oyster juveniles is excellent, population recovery is impossible if the dispersing larvae—in the water column for 2-3 weeks—are choking on pollution or on the abundant suspended sediment caused by upstream erosion,” cautioned Hare.

“In our current research, including work funded by a recent New York Sea Grant award, we want to understand why larval production by the TZ-HB remnant oyster population is not generating more downstream settlement, closer to the city, even when attractive settlement substrates are provided,” said Hare.

The researchers stressed that the adaptive capacity provided by high genetic diversity is important in the dynamic estuarine environment. Given climate change projections for an increased frequency of intense storms that dramatically change the salinity conditions, it will be important during restoration efforts to make sure genetic diversity is maintained.

Overall, this study not only identifies several areas of favorable habitat for oyster comebacks across the HRE, it motivates and informs new ways to approach HRE oyster restoration in the future.

(At left) Nils Wendel (a summer student assistant) and Chaz Hyseni (former Sea Grant Scholar) checking for spat (juvenile oysters) in shell bags at NYC’s Anable Basin site, July 2013; (At right) A timeline mapping out when and exactly where samples were taken from throughout the Hudson/Raritan Estuary during the study. Credit: Matthew Hare.

References

1 McFarland K, Hare MP (2018) Restoring oysters to urban estuaries: Redefining habitat quality for eastern oyster performance near New York City. PLoS ONE 13(11): e0207368. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0207368 PMID: 30444890

More Info: New York Sea Grant

New York Sea Grant (NYSG), a cooperative program of Cornell University

and the State University of New York (SUNY), is one of 34 university-based

programs under the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s

National Sea Grant College Program.

Since 1971, NYSG has represented a statewide network of integrated

research, education and extension services promoting coastal community

economic vitality, environmental sustainability and citizen awareness

and understanding about the State’s marine and Great Lakes resources.

Through NYSG’s efforts, the combined talents of university scientists

and extension specialists help develop and transfer science-based

information to many coastal user groups—businesses and industries,

federal, state and local government decision-makers and agency managers,

educators, the media and the interested public.

The program maintains Great Lakes offices at Cornell University, SUNY

Buffalo, SUNY Oswego and the Wayne County Cooperative Extension office

in Newark. In the State's marine waters, NYSG has offices at Stony Brook

University in Long Island, Brooklyn College and Cornell Cooperative

Extension in NYC and Kingston in the Hudson Valley.

For updates on Sea Grant activities: www.nyseagrant.org has RSS, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube links. NYSG offers a free e-list sign up via www.nyseagrant.org/nycoastlines for its flagship publication, NY Coastlines/Currents, which is published quarterly. Our program also produces an occasional e-newsletter,"NOAA Sea Grant's Social Media Review," via its blog, www.nyseagrant.org/blog.