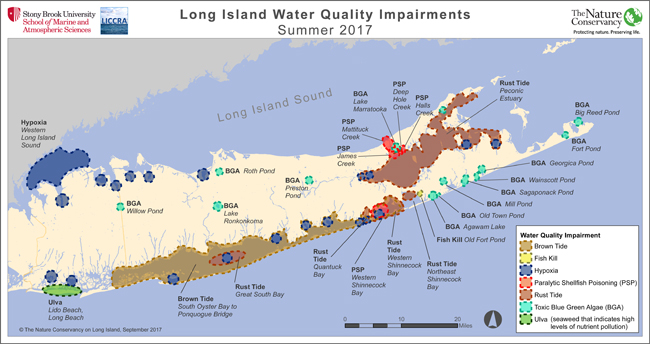

In addition to hypoxia (a deficiency of dissolved oxygen) and blue-green algae, some of the problems found in 2017’s water quality assessment were brown tides on the South Shore, rust tide in the Peconic bays and paralytic shellfish poisoning on the East End — all of which are also nitrogen and/or phosphorous level issues that can be traced back to cesspool sewage and fertilizers. The good news, said Dr. Christopher Gobler at the "State of the Bays" address in early April 2017 at Stony Brook Southampton, is that “politicians are owning the issue,” acknowledging that sub-standard septic systems are responsible for about 2/3 of the nitrogen entering the bays. For more on Long Island's 2017 water quality concerns, see "State of the Bays: Communities Respond to Colorful Tides that Could Signal Harm." Credit: Chris Gobler.

— By Chris Gonzales, Freelance Science Writer, New York Sea Grant

Stony Brook, NY, June 21, 2018 -- 2017 was one of the worst years for brown and red tides, both considered harmful algal blooms (HABs), in Long Island’s waters.

For the 2018 season, “since nutrient loads have not changed, [we can expect] more of the same,” notes Dr. Christopher Gobler, an expert in the region’s water quality issues.

Last summer, Long Island’s waters experienced a 10-week-long brown tide. It was not only one of the longest, it was one of the most intense on record.

For nearly two decades, Gobler – the Associate Dean for Research and a professor at Stony Brook University’s (SBU) School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences (SoMAS) –has received support from New York Sea Grant (NYSG) to raise awareness about HABs through research and outreach efforts.

On Friday, May 4th , Gobler gave his annual “State of the Bays” talk SBU’s Southampton campus. The speech has become a noted annual event, where the scientist talks about the environment, water quality, and what folks can do who are heading out to enjoy recreation on Long Island’s bays and beaches.

“Water is at the core of the Long Island existence. We rely on groundwater to drink. That same groundwater is the primary source of freshwater and nitrogen to our coastal ecosystems,” Gobler said.

“We are surrounded by water within which we swim, boat, and recreate,” he continued. And so, with recent trends in water quality on Long Island having been troublesome, there’s an increasing cause for concern.

“Toxic chemicals are contaminating drinking water supplies,” says Gobler. “Nitrogen levels in groundwater have risen by more than 60% in recent decades and coastal ecosystems have suffered.” Much of the nitrogen that ends up in Long Island’s waterways, where it fuels algae and the blooms they form, is from untreated wastewater, an issue that local government is trying to address. For example, Suffolk County’s HABs Action Plan, which was released in late September 2017, lays out a strategy for monitoring, research, and management. It includes proposals for limiting nitrogen, such as upgrading septic systems; deploying seaweed farms and shellfish aquaculture facilities; and monitoring for toxins. For more on this plan, which NYSG and Gobler helped prepare, see "State of the Bays: Action Plan Released on Harmful Algal Blooms."

“Since the late 20th Century,” Gobler continues, “aerial coverage of critical marine habitats on Long Island such as eelgrass and salt marshes have declined by up to 80% and Long Island’s top shellfisheries have declined by up to 90%.” For more on the water quality connection with both the steep drop in habitat and shellfish, see results from a related NYSG-funded research study in “Changes in the Ocean Affect Economically Important Shellfish.”

For this project, Gobler collected water samples from around Long Island, in particular from its South Shore Estuary Reserve (SSER) waters from Shinnecock Bay through Great South Bay. The purpose of this effort was to gather information that could foretell the fate of New York’s three most valuable bivalve fishery species: hard clams (Mercenaria mercenaria), eastern oysters (Crassostrea virginica) and bay scallops (Argopecten irradians). These bivalves are not only delicacies; they filter and clean the water, and thus may be part of the HAB solution.

“Many of New York’s estuaries already face seasonal acidification and hypoxia,” says Gobler, the latter of which signifies low levels of dissolved oxygen in those waters. “These conditions will intensify with near-term climate change. It is important that regions and species of bivalves least susceptible to these conditions be identified now in order to maximize the resilience of New York’s bivalve populations and seafood supply for the future.”

Through some of Gobler’s other NYSG-funded work the investigator hosts workshops on water quality in Long Island estuaries. Additionally, he is studying concentrations and exchanges of nitrogen (a growth nutrient for various algal blooms) between estuarine sediments and the overlying waters.

“In our recent [NYSG-funded] research, we are tracking nutrient inputs from sediments and how they related to HABs,” says Gobler.

HABs degrade water quality, and can lead to hypoxia (oxygen-depleted waters), acidification (a process by which absorption of carbon dioxide gas produces a pH imbalance in these waters, making them more acidic), fish kills, and decline in valuable bivalve species.

August 1, 2017 marked the end of one of the longest and most intense brown tides on Long Island on record (10 weeks). "What began at an ominously early time (early May) and in a strangely uncommon place (South Oyster Bay), spread to cover the entire south shore of Long Island by early June and persisted in Great South Bay [pictured above; Credit: Chris Gobler] through late July, marking one of the longest brown tide on record. It was the most intense brown tide ever, reaching peak intensity of 2.3 million cells per milliliter in Bay Shore in early July."

The ABCs of HABs

To the casual observer, HABs first appear as a mysterious, unusual color in the water: red, brown, green, or sometimes blue-green. However, the colorful displays wreak havoc in marine habitats, as blooms can be a nuisance or set off damage in ecosystems. Algae can also make the family dog sick, or cause death, just as it may cause illness or even death in humans.

While the color gives rise to common names such as red tide or brown tide, scientists use the technical term “HABs” to denote several types of “harmful algal blooms,” which are defined as conditions when a subset of algal species—tiny aquatic plants—produce toxins or grow excessively, harming humans, other animals and the environment.

As murky, algae-filled water washes up on shores, several major types of threats could be present. One class of HABs is harmful to marine life. This includes the microscopic alga Aureococcus anophagefferens, which may bloom in such densities that the water turns dark brown, a condition known as “brown tide.” Brown tides are known for blocking light, knocking down the eel grass that fish and shellfish rely on for habitat.

Another group of HABs on Long Island can cause illnesses such as paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP) if people consume shellfish that have been feeding in the affected area. The most common of these HABs is the dinoflagellate Alexandrium. Some symptoms can range from nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and cramps. In severe cases, people can be afflicted with dizziness, headache, seizures, disorientation, short-term memory loss, respiratory difficulty and even coma.

When asked what folks can do to help, Gobler says, “Be aware of current conditions, and take steps to reduce your nitrogen footprint.” For example, follow media reports about water conditions, make sure your residential septic system is functioning properly, and avoid situations where residential nitrogen application could run off into local tributaries.

In addition, when folks head out to enjoy recreation this summer, look for “clean, well-flushed waters,” says Gobler. This means the water has been moving, not stagnant, and looks clear and bright.

More Info: New York Sea Grant

New York Sea Grant (NYSG), a cooperative program of Cornell University

and the State University of New York (SUNY), is one of 33 university-based

programs under the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s

National Sea Grant College Program.

Since 1971, NYSG has represented a statewide network of integrated

research, education and extension services promoting coastal community

economic vitality, environmental sustainability and citizen awareness

and understanding about the State’s marine and Great Lakes resources.

Through NYSG’s efforts, the combined talents of university scientists

and extension specialists help develop and transfer science-based

information to many coastal user groups—businesses and industries,

federal, state and local government decision-makers and agency managers,

educators, the media and the interested public.

The program maintains Great Lakes offices at Cornell University, SUNY

Buffalo, SUNY Oswego and the Wayne County Cooperative Extension office

in Newark. In the State's marine waters, NYSG has offices at Stony Brook

University in Long Island, Brooklyn College and Cornell Cooperative

Extension in NYC and Kingston in the Hudson Valley.

For updates on Sea Grant activities: www.nyseagrant.org has RSS, Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube links. NYSG offers a free e-list sign up via www.nyseagrant.org/nycoastlines for its flagship publication, NY Coastlines/Currents, which is published quarterly. Our program also produces an occasional e-newsletter,"NOAA Sea Grant's Social Media Review," via its blog, www.nyseagrant.org/blog.