Hurricane Harvey Reaches Peak Intensity on August 25, 2017. Credit: NOAA.

Examining Public Responses to Severe Storm Threats and Empowering Preparedness

New York, NY, September 10, 2018 - How will you and your loved ones stay safe when a severe storm hits?

Each year, "Hurricane Preparedness Week" (March) and "National Preparedness Month" (September) serve as reminders that planning is important.

The most effective way is to have a plan in place. It's easy to panic during an emergency; being mentally and physically prepared can help to minimize that feeling of panic and enable you to keep your family calm, cool, collected, and most importantly, safe.

Four questions that can help you begin to develop an emergency plan:

- How will I receive emergency alerts and warnings?

- What is my shelter plan?

- What is my evacuation route?

- What is my family/household communication plan?

In late October 2012 as Superstorm Sandy battered the U.S. East Coast, residents in communities along the Connecticut shore received “mandatory” evacuation orders, but most people didn’t leave.

Was this an example of poor planning or a smart precautionary decision?

According to findings from a post-Sandy study led by Yale University's Jennifer Marlon, a survey of 1,130 people living along the state’s coastline offered some insights into why some people decide to evacuate in the face of a weather emergency and why others try to ride out the storm.

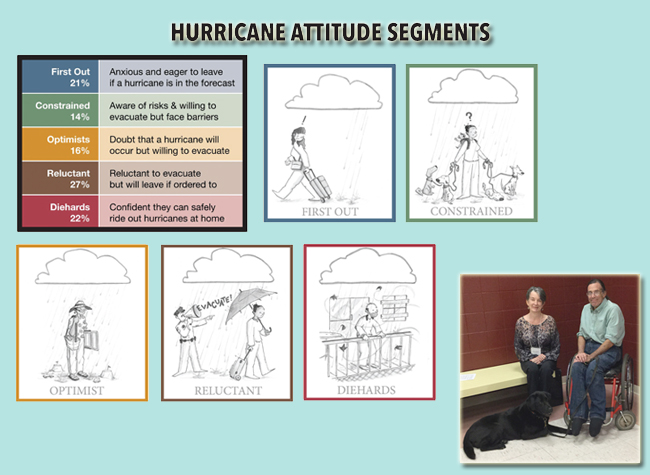

The study, conducted by the Yale Project on Climate Change Communication as part of the NOAA Sea Grant Coastal Storm Awareness Program (CSAP) administered by Connecticut, New Jersey and New York Sea Grant, identified five different types of people based on how they respond to hurricanes. They are:

- The First Out (21%) will evacuate for any hurricane.

- The Constrained (14%) would like to evacuate, but face barriers to leaving.

- The Optimists (16%) are doubtful that a hurricane will ever hit them, but will evacuate if needed.

- The Reluctant (27%) will leave only if ordered to.

- The Diehards (22%) are confident they can ride out the storm and won’t evacuate.

When it comes to facing severe coastal storms, there are a variety of roles that residents can play. Yale University's Jen Marlon (not pictured above) used a survey analysis to group respondents from the Connecticut coastal flood zone in five groups of attitudes and behaviors (which are depicted above). One strong message from a related study (by SUNY ESF investigators Sharon Moran and William Peace, pictured above, at bottom right) was that the rights of disabled persons (those in the "constrained" group) and service animals need to be addressed in evacuation planning. Credit: Peg Van Patten/CTSG; Illustration: ©Chris Cater / From J. Marlon et al., 2015, Yale University.

- The First Out perceive the greatest risk from hurricanes and are likely to evacuate if one is forecast to make landfall nearby. Of the First Out residents who experienced Superstorm Sandy, 55% evacuated.

- The Constrained understand the risks of staying home during a hurricane, but feel they would have trouble evacuating if they wanted (or needed) to due to age (elderly), poor health/disability, pets, or lack of money. 22% of the Constrained evacuated during Superstorm Sandy – the highest proportion aside from the First Out.

- Optimists have the lowest expectations of all the groups that a hurricane of any strength will occur in the next 50 years, although they say they would evacuate if one did occur. Perhaps because they think hurricanes are so unlikely, Optimists are the least prepared and most likely of all the groups to perceive significant barriers to evacuating, such as health/disability issues, lack of money, and lack of know-how.

- The Reluctant are less afraid of hurricanes than average and tend to live farther from the coast than the other groups. However, Reluctant individuals would evacuate if told to do so by a relevant authority – especially local police or fire departments, another local government official, or the Governor’s Office. Like the First Out, the Reluctant do not perceive significant barriers to their evacuation, and with an evacuation order, they are likely to evacuate at levels similar to the First Out.

- Diehards have the lowest hurricane risk perceptions of all the groups and are the least likely to evacuate. Diehards feel self-reliant and confident that they can protect themselves; they also believe it is safer to stay home than to evacuate so they can protect their property. Pets are an important barrier to leaving for 25% of the Diehards. Of the Diehards who experienced Superstorm Sandy, only 6% evacuated.

All of the segments are most likely to evacuate if they receive an evacuation order from local officials, whether police, fire, or other government workers (as compared with announcements from weather broadcasters or other sources on the TV or radio).

The unique perceptions and needs of coastal Connecticut residents in the event of a hurricane underscores the importance of tailoring messages about storm preparedness, the nature of storm hazards and the likelihood of different damages, as well as evacuation resources. Some groups understand the risks and need minimal information in order to respond appropriately, whereas others understand the risks but need assistance. Still others misunderstand the risks and thus require education and outreach efforts well before a hurricane makes landfall.

Before The Storm: Hurricane Preparedness

Hurricanes are among nature’s most powerful and destructive phenomena.

Hurricanes are most common during June 1 to November 30. Strong winds,

waves, storm surge, flooding are a few of the many hazards that are

associated with hurricanes.

New York City has experienced hurricanes and we have learned to increase our preparedness to these hazards.

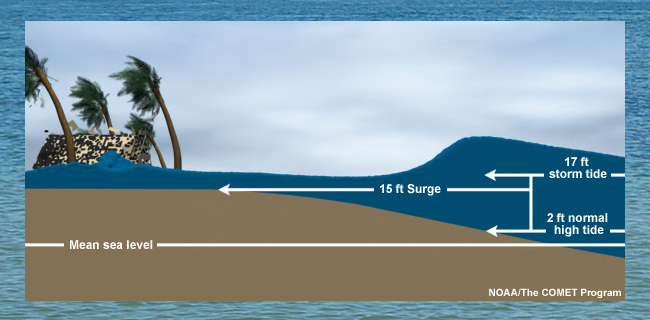

One of the biggest concerns linked to severe storms: Storm Surge,

which is flooding from water that is pushed onto land from the ocean as

a hurricane approaches the shore. It can cause significant damage and

threaten life and safety.

When a hurricane threatens a community, it is important for coastal

residents to understand the risks from storm surge and know what to do

to be safe. However, communicating storm surge risk is difficult because

of the complex interactions between storms, coastlines, and

communities.

- Storm surge is caused primarily by the strong winds in a hurricane or a strong storm.

- Storm surge is an abnormal rise of water generated by a storm, over and above the predicted astronomical tide.

- Storm tide is the water level rise during a storm due to the combination of storm surge and the astronomical tide.

Here are some tips to keep you and those in your life safe ...

First, FEMA encourages you to be aware ...

Second, Sea Gran offers you some recommendations on preparation ...

- Keep a battery-operated AM/FM radio tuned to a local station and follow emergency instructions.

If it is safe to evacuate, take your Go Bag with you.

- If you're caught inside by rising

waters, move to a higher floor. Take warm clothing, a flashlight, and

portable radio with you. Wait for help. Do NOT try to swim to safety.

- When outside, avoid walking and

driving through flooded areas. As few as six inches of moving water can

knock a person over. Six inches of water will reach the bottom of most

passenger cars, causing loss of control and possible stalling. One or

two feet of water can carry away a vehicle.

- If you have to walk in water, walk

where the water is not moving or use a stick to check the firmness of

the ground in front of you.

- Stay out of any building if it is surrounded by floodwaters.

If time permits:

- Turn off all utilities at the main power switch and close the main gas valve if evacuation appears necessary.

- Do not touch any electrical equipment

unless it is in a dry area, or you are standing on a piece of dry wood

while wearing rubber-soled shoes or boots and rubber gloves.

- Fill bathtubs, sinks, and jugs with

clean water in case regular supplies are contaminated (you can sanitize

these items by first rinsing with bleach).

- Board up windows or protect them with storm shutters or tape (to prevent flying glass).

- Bring outdoor objects, such as lawn furniture, garbage cans and other loose items, inside the house or tie them down securely.

Visit New York City Emergency Management Web site for more information.

Severe Storms: Sea Grant on Lessons Learned from Superstorm Sandy

The 4-1/2 minute trailer for NOAA Sea Grant's Coastal Storm Awareness Program's 23-minute documentary, view-able on YouTube.

The key to CSAP, a $1.8M suite of 10 social science projects

administered by Sea Grant programs in New York, New Jersey and

Connecticut, is to help better understand how people respond to coastal

storm warnings. "These storms will not go away," said NYSG former Director Bill Wise (retired). "They are likely to increase and, perhaps, become even more severe on average with global warming."

Findings from these 18-month community-based investigations are detailed in the news item "NOAA Sea Grant Coastal Storm Awareness Program Comes Ashore."

For more on NOAA Sea Grant's Coastal Storm Awareness Program see www.nyseagrant.org/csap.

More Info: New York Sea Grant

New York Sea Grant (NYSG), a cooperative program of Cornell University

and the State University of New York (SUNY), is one of 33 university-based

programs under the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s

National Sea Grant College Program.

Since 1971, NYSG has represented a statewide network of integrated

research, education and extension services promoting coastal community

economic vitality, environmental sustainability and citizen awareness

and understanding about the State’s marine and Great Lakes resources.

Through NYSG’s efforts, the combined talents of university scientists

and extension specialists help develop and transfer science-based

information to many coastal user groups—businesses and industries,

federal, state and local government decision-makers and agency managers,

educators, the media and the interested public.

The program maintains Great Lakes offices at Cornell University, SUNY

Buffalo, SUNY Oswego and the Wayne County Cooperative Extension office

in Newark. In the State's marine waters, NYSG has offices at Stony Brook

University in Long Island, Brooklyn College and Cornell Cooperative

Extension in NYC and Kingston in the Hudson Valley.

For updates on Sea Grant activities: www.nyseagrant.org has RSS, Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube links. NYSG offers a free e-list sign up via www.nyseagrant.org/nycoastlines for its flagship publication, NY Coastlines/Currents, which is published quarterly. Our program also produces an occasional e-newsletter,"NOAA Sea Grant's Social Media Review," via its blog, www.nyseagrant.org/blog.