NOTE: All content below can be found in the poster version of "The Great Lakes Basin" (pdf)

Funding for the printing of this document was provided by the New York State Environmental Protection Fund under the authority of the New York Ocean and Great Lakes Ecosystem Conservation Act.

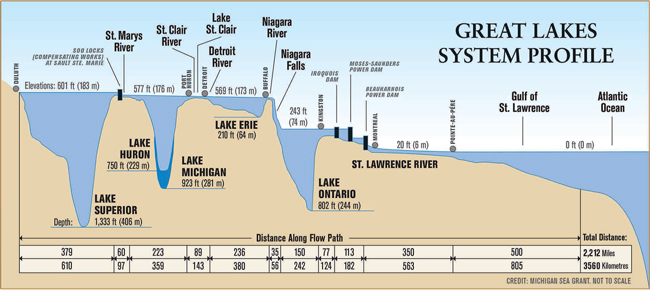

Buffalo, NY, June 24, 2016 - The Great Lakes — Superior, Michigan, Huron, Erie and Ontario — contain 20% of the world’s fresh surface water and provide the water necessary for the basin’s agriculture, industry, hydroelectric power and recreational activities like fishing and boating. The 6 quadrillion gallons of fresh water in the Great Lakes can be used for drinking water for millions of people living nearby in the United States and Canada. The Great Lakes were called the “Sweetwater Seas” by sailors, and they are so large in size, their outline can be seen from the moon.

The large surface area of the Great Lakes can influence local climate, create a thermal lag by keeping shoreline areas cooler in the summer and help moderate winter temperatures around the basin. Lake-effect rain and snowstorms impact communities and provide impressive snow records in many winters. The coastal regions of the Great Lakes contain microclimate areas that are less prone to late spring and early fall frosts, which is ideal for the many fruit orchards and vineyards that add to the economy of the basin.

The Great Lakes are an incredible resource that influences the lives, economies and communities that ring their shoreline. From tourism that brings millions of visitors to parks and beaches, to shipping that utilizes this “Highway H2O” to move cargo, the Great Lakes serve as an economic driver to North America. The importance of the Great Lakes is not only counted in dollars and cents, but also the intrinsic value of their beauty and majesty by those who take in their scenic views and natural lands.

Geology

The Great Lakes were formed by the advancing and retreating of glaciers that gouged and shaped the basin over thousands of years from the Great Ice Age to approximately 10,000 years ago, when the lakes took on their present shape. Over several different glacial periods, ancient riverbeds provided the beginnings of some of the Great Lakes. The east-west fetch of Lake Erie followed one of these ancient rivers and became wider and deeper over time, until it reached its present size and shape. Like giant bulldozers, the glaciers moved the resistant bedrock and easily scoured the softer sandstone and shale. As the glaciers moved over the area, they created the Niagara Escarpment that covers parts of Ontario, New York, Michigan, Illinois and Wisconsin, and formed the mighty Niagara Falls. These glaciers were more than a mile thick and left behind huge boulders and unusual rock formations that can be seen today as the “flowerpots” on Bruce Peninsula in Ontario, Canada.

Millions of years before the glaciers carved out the Great Lakes, the area where the basin lies was once covered by a shallow, tropical sea. The sands, salts and minerals of that sea can be found beneath the Great Lakes as deposits of halite, gypsum, oil and gases. Even today, fossils from prehistoric sea creatures like clams and crinoids, corals and large trilobites can be unearthed around the basin.

Early History

The Paleo-Indians were the first people to occupy the area we know as the Great Lakes Basin. These hunters depended on mammals like bear, beaver and elk for survival. The Paleo-Indians were followed by early settlers who were able to use copper to form tools and weapons. Over time, early Native Americans in the region included Ojibwe (Chippewa), Fox, Iroquois, Ottawa, Potawatomi and other tribes.

Early European settlers are given credit for “discovering” the Great Lakes. These settlers came in search of a new passage to the Orient through the Northwest Passage. Instead, with the help of the Native Americans, they established settlements and survived in the harsh conditions. The French continued to settle the basin as trade in furs, especially beaver pelts, became an important commodity. The British soon realized the resources available from the Great Lakes region and European settlement steadily increased. The opening of the Erie Canal in 1825, brought a new way to ship the white pine and other lumber of the Great Lakes to the eastern shores of America. The Erie Canal also provided a way to move people and goods to the expanding regions around the Great Lakes and the Midwest. Soon, towns and cities spread out across the basin as people cleared the land for agriculture and relied on the natural resources like fish and animals from the region. The Great Lakes and their boundless resources played an important role in helping young, fledgling America become a world leader

Modern Great Lakes

As cities grew, so did the inevitable toll on the natural resources of the Great Lakes. Commercial fishing played an important role in the early economy, but the excessive fishing pressure on stocks, improved methods and efficient equipment like steam-powered gill boats, soon resulted in overfishing and declines of important species like whitefish and Atlantic salmon. Early settlements built dams to harness water power for lumber and gristmills, further impacting the fishery as they stopped important spawning runs for many fish species. Even before 1900, the commercial fishery in the Great Lakes was in need of management and regulation. In 1955, the Great Lakes Fishery Commission was established by the Canadian-U.S. Convention on Great Lakes Fisheries. The Fishery Commission coordinates fisheries research, facilitates cooperative fishery management among the state, provincial, tribal, and federal management agencies, and is responsible for controlling the invasive sea lamprey.

Pollution soon became a problem around the Great Lakes, as more and more people crowded cities in search of jobs and a better life than they left in Europe. Human and industrial wastes found their way to the once pristine waters of the Great Lakes as contaminants, heavy metals and industrial by-products created water quality issues. Phosphorus level increased and brought about a growth of nuisance algae. Areas of low oxygen levels (anoxia) caused fish die offs and in the late 1960’s Lake Erie was considered “dead.” An outcry from concerned citizens soon brought about a ban on detergents that contained phosphorus and other efforts to improve the water quality of the Great Lakes. These early environmental efforts helped to pass the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement between Canada and the U.S. in 1972. The Agreement was amended in 1987, and most recently in 2012, when provisions were added to address aquatic invasive species, habitat degradation, and the effects of climate change.

Today's Stressors

Invasive species, harmful algal blooms, habitat destruction, altered land use, and non-point source pollution are some of the stressors that impact the Great Lakes today. The impact of future climate change has the potential to bring additional ecosystem impacts, along with the economic and the human toll of increased and more severe storms.

Invasive Species

From the spread of the sea lamprey with the opening of the Erie and

Welland Canals in the early 1980’s, invasive species have impacted the

environment of the Great Lakes. Today, more than 180 invasive species,

from the alewife to zebra mussels, make their home in the Great Lakes.

The invaders compete for food and habitat, alter food webs and have

caused the extinction of some native species.

Zebra and quagga mussels have had a profound impact on the Great Lakes

since their arrival in ships’ ballast water in the late 1980s. The

original zebra mussel (Dreissena polymorpha) and the related quagga

mussel (Dreissena rostriformis bugensis) that arrived a few years later,

are responsible for changes in the food web. They filter out plankton

and other particles from the water, reducing the available food for

other species. Both species of mussels are prolific breeders and their

numbers grew rapidly. Quagga mussels are found in colder, deeper areas

of the Great Lakes, often covering the substrate hundreds of feet below

the surface.

The filtering activity of zebra and quagga mussels has increased water

transparency in the Great Lakes. The increased light penetration allows

for more algal and plant growth in the water. This water clarity often

results in people believing the mussels have “cleaned-up” the Great

Lakes, but in actuality they have only made the water clearer. In fact,

as mussels filter water close to the bottom of the lakes, they can

actually take up pollutants, contaminants and bacteria that can become

part of the food web when mussels are consumed by bottom-dwelling fish

like round gobies.

Like zebra and quagga mussels, the round goby (Neogobius melanostomus)

was introduced in ballast water from ships coming from the Black and

Caspian Seas in Europe. These aggressive fish feed actively on the eggs

of many Great Lakes fish like lake trout, bass and whitefish. They also

compete with other benthic (bottom-dwelling) fish like sculpin and

darters, reducing their numbers. Gobies are easily identified by their

suction cup-shaped, fused pelvic fins. No other Great Lakes fish has

this suction disk on its belly. Round gobies have highly developed

sensory systems that allow them to avoid predators and detect prey. They

are also capable of multiple spawnings (up to 6 times per year),

allowing them to quickly increase and maintain the size of their

populations.

The sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus) is referred to as the “vampire” of

the Great Lakes since it is a parasitic fish that feeds on the blood and

body fluids of other fishes. Originally from the Atlantic Ocean, sea

lamprey made their way to Lake Ontario through the St. Lawrence River

and moved through the other Great Lakes with the opening of the Erie and

Welland Canals. Sea lampreys have a sucker-like mouth ringed with sharp

teeth that they use to attach to fish. Once firmly anchored, sea

lampreys use a rasping tongue to break through the slime and scales

before feeding. Special enzymes are released by the lamprey that prevent

the fish’s blood from clotting, allowing the lamprey to continue its

meal. Sea lampreys take a toll on the fishes of the Great Lakes, often

targeting fish with small scales like whitefish, lake trout and salmon.

The Great Lakes Fishery Commission is charged with controlling sea

lamprey populations and they use a variety of techniques including

Lampricides (pesticides to target lampreys), traps and barriers.

People are encouraged to help reduce the spread of invasive species by

cleaning their boats and trailers before moving them to other areas,

draining live-wells, properly disposing of bait and taking other steps.

Visit www.protectyourwaters.net to learn more about the Stop

Aquatic Hitchhikers! campaign and what you can do to slow the spread of

aquatic invasive species.

Although many aquatic invasive species (AIS) have spread through the

Great Lakes by ballast water, bait bucket dumping and hitchhiking on

recreational boats and trailers, these are not the only means of

introductions. Recently, efforts have been made to prevent the

introduction or spread of AIS through the aquarium and nursery trades

and classroom release. These organisms in trade (OIT) pathways provide a

significant threat to the health of the Great Lakes. The release or

escape of aquarium fish, reptiles, amphibians and invertebrates, as well

as the spread of non-native plants have the potential to alter

ecosystems and impact food webs. Notorious examples such as the northern

snakehead fish (Channa argus), red swamp crayfish (Procambarus

clarkii), goldfish (Carassius auratus), and plants, like Eurasian

watermilfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum) and hydrilla (Hydrilla

verticillata), have been released or escaped from aquaria, backyard

ponds or water gardens. The Habitatittude campaign focuses on protecting

the environment by teaching people about not releasing unwanted plants

and animals. See habitattitude.net to learn more about this

program.

Harmful Algal Blooms

One of the most pressing issues today in Lake Erie, especially in the shallow western basin, is harmful algal blooms (HABs) that have changed the once clear waters into a bright green soup. Although single celled organisms, including algae, are an important part of the food web, some blooming organisms can contain toxins or noxious chemicals. Many algal blooms are harmless, but blooms of cyanobacteria, like Microcystis aeruginosa, Anabaena circinalis, Anabaena flos-aquae, and Aphanizomenon flos-aquae, can contain toxins. These toxins can include nerve toxins (neurotoxins), liver toxins (hepatotoxins), and skin irritants.

Although a water restriction crisis in the Toledo, Ohio, area during the summer of 2014 focused the national spotlight on this issue, harmful algal blooms are not a new phenomenon to Lake Erie. During the 1960s and 1970s, the lake had massive cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) blooms due to cultural eutrophication. As the lake was cleaned up, these blooms seemed to diminish until the mid to late 1990s. Since then, the lake has seen significant numbers of HABs and recent blooms have been much more widespread than those of the past.

Habitat Destruction

Habitat destruction is a major issue in the Great Lakes, especially the ecologically important wetland areas that serve as spawning and nesting habitat for fishes and animals. Wetlands are some of the most biologically diverse areas in the basin and play a major role in water quality and erosion control. Unfortunately, many of the wetlands of the Great Lakes have been filled in and destroyed. In some areas of the Great Lakes, up to 90% of the original wetland areas are gone, being replaced by agriculture, industry or shoreline communities.

Land use practices continue to be a concern throughout the Great Lakes Basin with development and urban sprawl changing the use of the land and water drainage from natural to altered states. The functioning of natural systems and the connectivity of habitats can be forever changed without proper planning. Communities need to focus on land use and sustainable planning to reduce the impact on the basin. A balance needs to be created between development and environmental protection, with the goal of conserving and enhancing natural areas as part of land use planning.

Pollution

Early on, the primary threat from pollution came from unregulated industrial dumping and discharges from antiquated water treatment facilities. This type of pollution is referred to as point source pollution since it comes from an identifiable source like the end of a discharge pipe. Contaminants like PCBs, mercury, mirex, and other pollutants impact the food web as they bioaccumulate in the tissues of birds, fish and mammals and move from one trophic level to another. In the past, chemical concentrations were so high that fish consumption advisories were put in place to protect residents around the basin. Even today, restrictions are still in place for some species of bottom-dwelling fish like bullhead and carp.

Fortunately, efforts have been made to strengthen or enact environmental laws and regulations to limit point source pollution in the Great Lakes, and millions of dollars have been spent to upgrade or replace outdated water treatment plants around the basin.

Nonpoint pollution comes from many diffuse sources and it is much harder to identify the point of origin. The primary source of nonpoint source pollution is runoff. Development and growth mean more roads, parking lots, roofs and other impervious surfaces that allow for the runoff of chemicals, fertilizers, oil and gasoline into streams, lakes and other waterways. Phosphorus and nitrogen run off residential lawns, parks, golf courses and farms, causing eutrophication problems in the Great Lakes.

Atmospheric depositions also pose a threat to the health of the Great Lakes Basin. These chemicals come from industrial smokestacks, coal-burning power plants, automobile emissions and the spraying of pesticides. Although the United States and Canada have enacted environmental protection laws and regulations, the airshed of the Great Lakes can be impacted by chemicals that originate from areas like Mexico and Central America, where laws are not as stringent. The chemicals in the air are washed back down to land through precipitation, in the form of rain and snow.

Today, it is the emerging chemicals of concern that are the focus of research and study. Fire retardants that are put on clothes and furniture, pharmaceutical byproducts that are flushed down toilets or poured down drains, microplastics that can be found in body wash and toothpaste all have the potential to harm the environment. Some of the chemicals are endocrine disruptors that have been reported as causing reproductive issues in animals and fish.

More Info: New York Sea Grant

New York Sea Grant (NYSG), a cooperative program of Cornell University

and the State University of New York, is one of 33 university-based

programs under the National Sea Grant College Program (NSGCP) of the

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The NSGCP

engages this network of the nation’s top universities in conducting

scientific research, education, training and extension projects designed

to foster science-based decisions about the use and conservation of our

aquatic resources. Through its statewide network of integrated

services, NYSG has been promoting coastal vitality, environmental

sustainability, and citizen awareness about the State’s marine and Great

Lakes resources since 1971.

New York Sea Grant maintains Great Lakes offices at SUNY Buffalo, the

Wayne County Cooperative Extension office in Newark and at SUNY Oswego.

In the State's marine waters, NYSG has offices at Stony Brook University

and Stony Brook Manhattan, in the Hudson Valley through Cooperative

Extension in Kingston and at Brooklyn College.

For updates on Sea Grant activities: www.nyseagrant.org has RSS, Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube links. NYSG also offers a free e-list sign up via www.nyseagrant.org/coastlines for its flagship publication, NY Coastlines/Currents, which is published several times a year.