Stony Brook, NY, August 31, 2011 - As Hurricane Irene headed up the U.S. East Coast late last week, New York Times environmental/climate-change reporter Andrew Revkin kept his Web visitors apprised of this force of nature via his interactive blog, Dot Earth.

Among his numerous related posts, Revkin picked up on data released by the Stony Brook Storm Surge Research Group, which has been funded principally by New York Sea Grant (NYSG) since 2002 to work on storm surge science, coastal defense systems and policy issues related to regional protection of New York City and Long Island.

Precipitation Map for Hurricane Irene, August 27, 2011, 9 pm

According to the Research Group, the New York Metropolitan region is vulnerable to coastal flooding and large-scale damage to city infrastructure from hurricanes, like Irene, and nor'easters. Much of this region - an area of about 100 square miles - lies less than three meters above mean sea level. Within this area lies critical infrastructure such as hospitals, airports, railroad and subway station entrances, highways, water treatment outfalls and combined sewer outfalls at or near sea level.

"Revkin featured our NYSG-sponsored work on storm surges, and in particular how accurately we were able to predict the intensity and timing of Hurricane Irene's related storm surges, both in the harbor and Long Island Sound," said Stony Brook University (SBU) Oceanography professor and a storm surge expert Malcom Bowman, also a member of the Group. "He also raised the issue of storm surge barriers and how the City has so far resisted the concept."

The simulation below, provided by the Storm Surge Research Group for one of Revkin's Irene-related posts on Saturday, August 27 shows the surge anticipated from New York Harbor around to Long Island Sound.In another entry from Sunday morning, August 28, the peak of Hurricane Irene in the New York Metro area (which was downgraded to a Tropical Storm in most areas), Revkin wrote, "In a conversation about the storm with Bowman late last night, we mused on whether Irene's impact would serve as a wake-up call prompting the city, which will face rising damage risk as sea levels rise in this century, to seriously consider storm surge barriers like those on the Thames [River Barrier in England]."

With NYSG funding, Bowman and other SBU researchers have studied the possibility of protecting the metropolitan New York City area from powerful storms through the use of storm surge barriers. Such barriers erected at several “choke points” (upper East River, Verrazano Narrows, Arthur Kill) would effectively seal off the area from incoming storm surge. A more ambitious scheme envisions a barrier/causeway from Sandy Hook, NJ to Far Rockaway, Long Island.

Stretching five miles across the approaches to New York Harbor in an area known as the New York Bight Apex, this barrier would serve double duty as a multi-line highway bypass between northern New Jersey and southern Long Island, including providing rapid access to JFK airport from points south. The causeway could also support a rapid-rail link between New Jersey and Long Island. This “outer-defense” would eliminate the necessity for both the Verrazano and Arthur Kill barriers, as well as protecting JFK airport, millions of residents in the outer boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens, and many communities in northern New Jersey.

As detailed in the simulation above from Revkin in his New York Times blog, "The first surge came around dawn [on Sunday, August 28], driven by an unusually high tide and the storm. The biggest [New York] City surge, driven by high tide and the storm, hit around 1 p.m." But, SBU researcher Dr. Brian A. Colle clarifies, "All predictions that I saw in the time series had the maximum surge around 5 a.m. - 9 a.m., and the storm arrived around 10 a.m. Our Group did a good job with the forecasts, and the fact that we run an ensemble of forecasts really helped compared to other models out there."

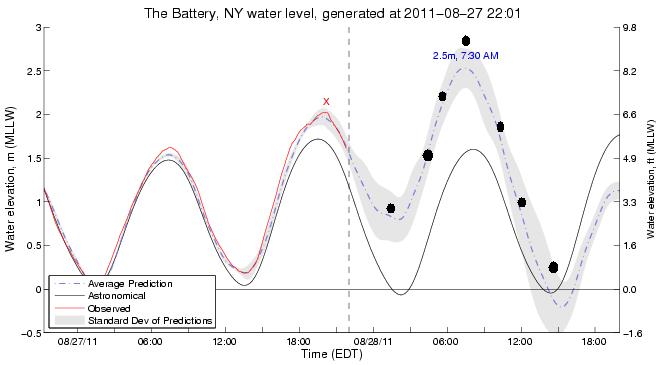

The graph below shows water levels down on the Battery, at the southern tip of Manhattan, with black circles illustrating peak observed elevations. In a recently NYSG-funded study, Colle looked at storm surges and the climatology of overall New York City the region. In published work, Colle and his researcher team sought to give forecasters and emergency managers a refined conceptual model of what local and regional atmospheric conditions are likely to cause flooding in the New York City area.

"The concept behind the Sea Grant project was to emphasize uncertainty, and you can see the spread in the peak surge. Although the observed was outside the shading, this is just the +/- 1 standard deviation or predictions, so the observed (9.5 ft Mean Lower Low Water, MLLW) was still possible. If we just did one surge forecast (similar to blue line) the forecast would have been way too low."

In case you are scratching your head, wondering what the observed water elevation calculation measured in MLLW means, Bowman explained, "There are two tides each day and they are usually not of the same magnitude. This is called diurnal inequality and is due to the inclination of the moon's orbit with respect to the earth's equatorial plane. By averaging only the the lower of the two daily low tides for a month gives us the Mean Lower Low Water reference. It is a useful baseline for ship navigation as it provides a measure of safety against running aground, as opposed to simply averaging all low tides for a month."

For more on this NYSG research project, see our Spring 2010 Coastlines article, "The Quiet Before the Storm?" (click here).

More About Hurricane Irene

While Hurricane Irene weakened before it hit New York, the swirling storm still packed a wallop, especially in low-lying areas in lower Manhattan, portions of Brooklyn, on Long Island's South Shore (eg., the Rockaways, Long Beach, Sayville and Babylon) and North Shore (eg., Port Jefferson and Stony Brook Village). At the end of this news item are some during/after Hurricane Irene pictures of some temporarily flooded Stony Brook Village locales from Stony Brook Harbor.

"It was the highest storm surge I have seen -- 5 foot -- in Long Island Sound, but the winds were out of the south and blowing away from the Island," said Jay Tanski, NYSG coastal processes specialist. "That meant you weren't getting the wave activity to cause the erosion that you would normally get with that high of a tide." And, he added, "When there are widely spaced waves, even if they are large, they can bring sand onshore."

As for Irene's effects, he said, "The biggest impact people may not have experienced before is

probably going to be the river/stream flooding in inland and perhaps some upstate New York

counties. On Long Island, the tree damage and loss of electricity is the issue."

Colle added, "Irene came with enough wind and rain to cause lots of downed trees, so up to 450,000 homes on Long Island alone lost power. Irene made landfall near Brooklyn as an upper tropical storm, with surface wind gusts of 60-70 mph across the Island. The sustained surface winds of approximately 40 mph were clearly weaker than expected."

Using observations from a vertical wind profiler located at Brookhaven National

Laboratory, Colle noted that "the storm did not simply weaken to less than category 1 strength overall, it had a 955 Millibars (mb) central pressure." Millibars is a measure of the pressure (or weight) of the air usually taken as close to the core of the hurricane as possible. As a general rule, the lower the pressure, the higher the winds.

"Also, there were hurricane force winds just above our heads, including category 2 winds at 1,000 meters (around 3,281 feet)," Colle continued, "but the big question was how to bring that momentum down to the surface with the stable layer near the ground. Some of that momentum was dragged down in heavy rainfall, and some of the peak 60-70 mph gusts occurred during this 4-5 a.m. period with a heavy precipitation band. Later in the day, the winds at greater heights decreased to 50-60 mph, but were mixed down more easily as the atmosphere cooled, which led to huge rolling eddies into Sunday evening." This vertical rolling of water, which is caused by a rapid increase in wind with height, sounded, as Colle described, "like a freight train of wind coming down the street.

"In terms of storm surge, the Battery got a 1.3 m (4.3 foot) surge at high tide Sunday morning, which put the total water level very close to the 1992 nor'easter (within 1 inch), so they got very lucky that water did not make it into the subway system - probably just a foot higher would have been big problems, and this whole idea of over-hyped storm surge in the media would not have been an issue. The surge during Gloria 1985 was 2.0 m (about 6.6 feet), but at low tide. If this sort of surge occurred during Irene, the subway could have been closed for a week."

"As with many tropical systems at this latitude, most of the heavy rainfall was left (west) of the predicted track, so over New Jersey into New England," Colle said. "Over a foot of rain was observed there, while Long Island only got a few inches. The flooding in New Jersey is epic, and appears to be worse than tropical storm Floyd back in 1999. I think we are only beginning to understand the scope of the problems there. This was a real wake-up for the media, since all the attention was near the coast (it's easy to put someone on the beach). But the real destruction and loss of life was with the inland flooding. There were forecasts warning of this, but it did not get the press coverage before the storm."

As for what is on the horizon, Colle said, "Now we have tropical storm Katia in the tropical Atlantic. It is at least 5 days from the Carribean, but the East coast may have to starting watching that later in the weekend. Hopefully it will recurve off to the north."

More About New York Times Dot Earth Blog

For more on Andrew Revkin's blog, check out a sample of Stony Brook Storm Surge Research Group-featured Dot Earth posts (click here) (pdf). Also, learn more about the Stony Brook Storm Surge Research Group in NYSG's May 2011 feature and related news items (click here).

In Dot Earth, New York Times writer Andrew C. Revkin examines efforts to balance human affairs with the planet’s limits. The blog, an interactive exploration of trends and ideas with readers and experts, is, as Revkin explains, built upon a concept of trying to strike a balance between a continued global population growth an a limited number of life-sustaining essentials: "By 2050 or so, the human population is expected to reach nine billion, essentially adding two Chinas to the number of people alive today. Those billions will be seeking food, water and other resources on a planet where, scientists say, humans are already shaping climate and the web of life." For more on Revkin's New York Times "Dot Earth" blog, go to dotearth.blogs.nytimes.com.

More About New York Sea Grant

New York Sea Grant (NYSG), a statewide network of integrated research, education, and extension services promoting the coastal economic vitality, environmental sustainability and citizen awareness about the State’s marine and Great Lakes resources, is currently in its 40th year of “Bringing Science to the Shore.” NYSG, one of 32 university-based programs under the National Sea Grant College Program of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), is a cooperative program of the State University of New York and Cornell University. The National Sea Grant College Program engages this network of the nation’s top universities in conducting scientific research, education, training, and extension projects designed to foster science-based decisions about the use and conservation of our aquatic resources.

Photo credits for below:

"during" Hurricane Irene, Sunday afternoon, August 28, 2011, courtesy of Malcolm Bowman

"after" Hurricane Irene, Monday afternoon, August 29, 2011, courtesy of Paul C. Focazio.