The Marine Sciences Research Center located at Stony Brook University’s Southampton campus. Stony Brook University and the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences (SoMAS) faculty will work on coastal science research projects on local oysters. Credit: Melissa Azofeifa/Statesman File.

— Published by Maria Lynders for Stony Brook University's The Statesman

(Filed under "Faculty / Long Island News")

Stony Brook, NY, December 1, 2020 - New York Sea Grant (NYSG), a cooperative program of Cornell University and the State University of New York (SUNY), has awarded more than $2.1 million to support six coastal science research projects, three of which are being led by Stony Brook University faculty.

The projects will explore topics that relate to and benefit New York’s coastal environment, communities and economies, with funding from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Sea Grant’s federal parent agency.

Marinetics Endowed Professor Bassem Allam, from Stony Brook’s School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences (SoMAS) is leading one of the six funded projects. The research will incorporate ploidy, the number of sets of chromosomes in a cell, and compare the performance of locally-derived triploid oysters with that of their diploid counterparts.

Allam explained that natural oysters, like humans and nearly all other mammals, are diploid, meaning each of their cells contains two sets of chromosomes. Some animals, however, can be induced to become triploid, which contains three sets of chromosomes. Oysters are one of those animals.

“We bred our oysters this past spring and they are now happily growing out in the fields in different places, in order to test different geographical locations,” Allam said.

He will further compare the performance of different oyster lines derived from different genetic backgrounds.

Any superior oyster lines identified during his study will be maintained and then broadly distributed to the aquaculture industry in the state and beyond. Allam said that he hopes the results of his research will help farmers better improve their aquaculture industries in N.Y.

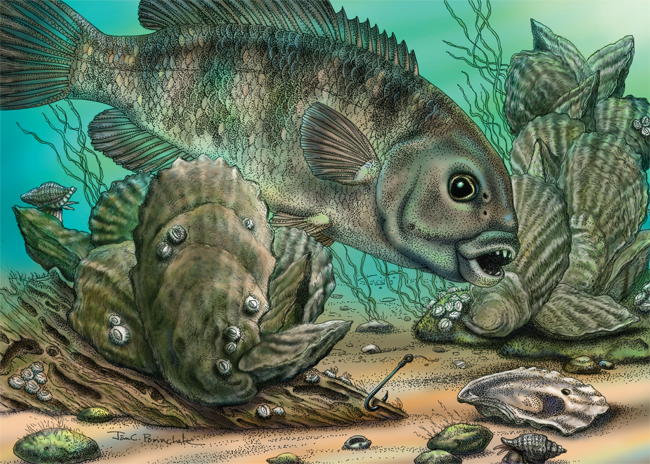

Oyster reefs were once a dominant feature of estuaries along the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico coasts with healthy communities of eastern oyster. New research supported by NY Sea Grant will provide information to support oyster restoration efforts in NY/NJ harbor. Credit: Jan Porinchak.

Allam’s research team, including Research Associate Professor Emmanuelle Pales-Espinosa and Professor Robert Cerrato, also from SoMAS, are about nine months into their two-year project.

“Triploid oysters were discovered to be feasible in the ‘70s and since then, there has been a growing interest in them,” Allam said. “This is because they are reproductively sterile, so they don’t put energy into reproduction and instead divert that energy for somatic growth so they can grow faster.”

There are two main pathways to produce a triploid oyster: chemical induction or by mating a diploid with a tetraploid oyster. Allam uses the mating process to produce his sterile oysters because he finds it a “safer option with better results.”

Allam emphasized that this process is not genetic modification — it is simply manipulating the basic mechanics of oyster reproduction.

He explained that a faster-growing oyster can be desirable for farmers because it means less exposure to disease and a higher yield. Some studies, he said, have reported up to a 70% to 80% higher yield.

But, not all oyster researchers have had that luck. Allam said that in some places in the nation, colleagues have reported unusually high mortalities in their triploid oysters.

“It is unclear why that occurred and it is not the case everywhere, but if that does happen in our research, we will attempt to understand the reasons behind it,” Allam said.

Allam explained many farmers in New York have varying results on growing triploid oysters.

“Is it good to grow triploid?” he said. “If you ask different farmers, you will get different answers because some saw benefits in some years, while others saw problems.”

Allam suspects the reason for these discrepancies may be partly due to the oyster’s genetic backgrounds. He pointed out that New York does not have hatcheries that produce systemically triploid oysters, and as a result, many farmers get triploid seed from out of state.

“A triploid oyster selected in Maine may not do so well growing in New York,” he said. “It is unclear if it is because of ploidy, unlikely in my opinion, or because of the genetic background.”

Phil Mastrangelo, an oyster farmer for Oysterponds Shellfish Company in Long Island, said he now grows 80% triploid oysters and 20% diploid oysters.

“Back when I only grew diploid, I had a lot of customers that would not take them after spawning and I would have to wait six to eight weeks because they were so thin,” he said.

Around 2014, Mastangelo started testing out triploids and found them to be more favorable to his growing conditions on Long Island.

“From my data, I find the triploids to be a bit more hardy than the diploids as far as weathering conditions, such as warmer water with less oxygen,” he said, “But there are many other factors involved, so it could also be from something else.”

He said he has spoken with other oyster farmers working nearby who have opposite data. Karen Rivara, a marine biologist and oyster farmer, has worked with Allam on projects in the past. She has experience in commercial hatcheries all across Long Island and is a founding member of the Noank Aquaculture Cooperative, a membership program for oyster farmers in Connecticut and Long Island. She used to spawn triploid seeds in her hatchery but stopped in 2016, returning to diploid only.

“Triploids are a pain to spawn so if I can do my business without them, I do,” she said. “Right now, I have enough demand for diploids.”

On top of that, Rivara explained she had to sign a sub-license agreement with 4Cs Breeding Technologies Inc., agreeing to make a 15% royalty payment of her gross income on all triploid seed and $50 per million triploid larvae sold or produced. Rivara also had to pay royalties to use the patented process to produce tetraploid and for the tetraploid broodstock.

The contract required her to keep accurate records of amounts and kinds of products made by the licensed technology and submit monthly reports to 4Cs on her operations.

“It wasn’t a huge deal,” she said. “Just an extra step and an extra expense to pass on to the customer.”

Rivara said if the demand for them increases, she might make a switch back to triploids in the future.

Steven Schnee, another oyster farmer on Long Island, said he has neither grown nor purchased triploid oyster seeds, though the thought of doing so did cross his mind.

“I thought about it, but I am not convinced it is worth the additional cost and care,” he said.

On the other hand, Schnee did express interest in Allam’s research.

“If he is able to super breed a particularly hardy, safe and healthy oyster, I would certainly be willing to try them and see what they are like,” he said.

New York oyster farmers will not be the only ones benefiting from Allam’s research. On Dec. 1 he began a similar study to compare ploidy and genetic backgrounds of oysters, but in a larger region, from Maine to Maryland.

More Info: New York Sea Grant

New York Sea Grant (NYSG), a cooperative program of Cornell University

and the State University of New York (SUNY), is one of 34 university-based

programs under the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s

National Sea Grant College Program.

Since 1971, NYSG has represented a statewide network of integrated

research, education and extension services promoting coastal community

economic vitality, environmental sustainability and citizen awareness

and understanding about the State’s marine and Great Lakes resources.

Through NYSG’s efforts, the combined talents of university scientists

and extension specialists help develop and transfer science-based

information to many coastal user groups—businesses and industries,

federal, state and local government decision-makers and agency managers,

educators, the media and the interested public.

The program maintains Great Lakes offices at Cornell University, University at Buffalo, SUNY Oswego and the Wayne County Cooperative Extension office

in Newark. In the State's marine waters, NYSG has offices at Stony Brook

University in Long Island, Brooklyn College and Cornell Cooperative

Extension in NYC and Kingston in the Hudson Valley.

For updates on Sea Grant activities: www.nyseagrant.org has RSS, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube links. NYSG offers a free e-list sign up via www.nyseagrant.org/nycoastlines for its flagship publication, NY Coastlines/Currents, which is published quarterly. Our program also produces an occasional e-newsletter,"NOAA Sea Grant's Social Media Review," via its blog, www.nyseagrant.org/blog.