80 years later, vivid memories of historic Long Island Express hurricane

On Sept. 21, 1938, the Category 3 storm took Long Islanders by surprise, claiming dozens of lives and turning the East End on its end.

- By Patricia Kitchen, Newsday

Bellport, NY, September 21, 2018 - They told stories of a yacht smashing through the front door. Of a saucer-eyed 6-year-old, making her way home through downed trees and wires. Of an attic refuge in a home filling with storm surge. Of a reprieve for a sole surviving featherless chicken.

Eight decades later, some voices cracked with emotion, but there was laughter, too, as witnesses to the 1938 Long Island Express hurricane shared recollections — for many still crystal clear after all these years.

“Somebody's house came across the bay and landed at our back door," said Jackie Parlato Bennett, 84. “We had to walk through that house to get out to the yard.”

On Sept. 21, 1938, the Category 3 storm took Long Island by surprise, slamming into Suffolk County with maximum sustained winds of 120 mph, and taking the biggest toll on areas east of Bellport, where it made landfall. The storm claimed around 60 lives on the Island and turned areas of the East End on end, scrambling the likes of boats, cars, houses, and poultry.

It also left an unforgettable impression on the young and impressionable.

“I remember a lot of it because it was so traumatic,” said Bennett. She was 4 years old on the day the winds blew and waters rose and delivered a summer resident's yacht — with the man still attempting to steer it — into the front door of her Westhampton Beach home, a block from the boat basin, giving entree to water that rose up to the windowsills.

“I remember the rest of it because my family talked about it forever … at the dinner table for the rest of my life,” she told the gathering, all from the Westhampton Beach area. And, the family never stopped looking at pictures, with her dad saying, “Don’t show the kid that,” when she got to the images of bodies “floating on their backs with the bellies all swollen from being soaked in the water. It was pretty gruesome.”

Some East End residents shared their memories of the 1938 Long Island Express hurricane at a gathering hosted Sept. 10 by the Westhampton Beach Historical Society. (Credit: Randee Daddona; Photo Credit: Westhampton Beach Historical Society, Suffolk County Historical Society)

The eight eyewitnesses were brought together Sept. 10 with an eye to formally collecting their stories to supplement those already documented in two remembrance booklets that marked the 50th and 60th anniversaries of the storm, said Jon Stanat, president of the Westhampton Beach Historical Society, which hosted the gathering. Those earlier accounts were from adults, but last week’s group included several members of what he called “the younger generation,” those who were as young as 4 and 6 years old at the time of the storm.

“The big picture,” of course, Stanat said, is that as each anniversary comes and goes, memories fade and witnesses pass on.

There certainly were some charming and gee whiz moments. Bennett told of a lone chicken that made it through the storm — featherless. Her father gave it a pardon, she said. “He didn’t have the heart to kill it, cause, if it could live through a storm like that, it had a right to live.”

Jackie Parlato Bennett, 84, was 4 years old when the hurricane hit but she remembers "a lot of it because it was so traumatic." Credit: Randee Daddona.

Lois R. Davis, 96, of Remsenburg, told of, observing from a school window, cherry tree after cherry tree succumbing to the fierce winds and toppling over onto teachers’ cars. And later, when taking in the sights with her sister, they were taken aback by the “shocking” image of an ordinarily dapper-suited man with his pant-legs rolled up, as he swept water from the front porch of his home, with the door left open.

And, she said, if people looked at the front door of the building they were in, “it was this front door. It was this house." After having been relocated, the house was later donated to the Westhampton Beach Historical Society and is now home to the Tuthill House Museum, which has a 1938 storm exhibit on display, open on Saturdays through the end of September.

There were plenty of tales of terror at the gathering, too.

On that day volunteers with cars were dispatched to take some school children home, recalled Joyce Warner Kelley, now 86 and then likely in second grade, she said.

The day before the Sept. 10 gathering of survivors, Jackie Parlato Bennett found a scrapbook that featured a newspaper clipping of children who rode out the storm. Fellow attendee Otis Bradley, second from left, was one of those children. Credit: Randee Daddona.

However, the approach to the Eastport duck farm she called home was impassable with fallen trees. “Can you believe they let out a 6-year-old to walk among those trees and wires?” she asked, with a hint of disbelief still after all these years. Making it home successfully, she says her mother told her “my eyes were as big as saucers. I guess I was pretty scared.”

Otis Bradley, of Quogue, then 6, found himself right at ground zero at a home on the bay side of Dune Road. His mother’s friend had invited his sister and him to join her two children and another child for lunch.

The winds came up, “out of the total blue,” he said, “and it hit.”

“You could see that water coming in — and coming in and coming in,” he said, with the group first going to the second floor, and then to the attic, according to an account in the first remembrance booklet.

Lois R. Davis, 96, recalls trees toppling onto teachers' cars at school. Credit: Randee Daddona.

As others had joined the group, men “smashed part of the roof, so we could see the bay and have an exit, in case the house fell,” according to the account, written by Bradley’s mother's friend.

Things were “so noisy,” said Bradley, 86, who “wasn’t looking a lot,” as he kept his eyes shut.

As for his feelings at the time? He was pretty scared, he said, with colorful emphasis. The episode was to provide fodder for nightmares for years to come.

Still, “every one of us lived,” he said, “which is amazing.”

This house on Dune Road was washed inland, onto the Westhampton Country Club. Credit: Westhampton Beach Historical Society.

Bradley's survival story was featured in a local newspaper — and Bennett just happened to have it in a scrapbook she came across the day before the gathering. The story featured a photo of Bradley when he was 6.

Another participant, Betty Warner, 95, recalled that the day of the storm parents were picking up their children at what was known as the Six Corners School in Westhampton Beach. Warner said her mother was not one of them.

“No one came for me, so I walked home,” she said, finding her mother there “on her hands and knees, mopping up rain water that had come in under the door.”

She recalls later being out walking with her father and coming across “a small dog on a mattress, soaking wet.” Its tag indicated it was from a town in New Jersey, so contact was made with the town clerk, who knew the owner. With much emotion in her voice, Warner said, “We kept it till they came and got him.”

Otis Bradley, 86, fled to the attic of a Dune Road home as the water kept "coming in and coming in." Credit: Randee Daddona.

On a further peculiar note, she told of their spotting in a nearby pasture a corner cabinet, “the cups still hanging on the hooks. The water just let it down easy.”

Ruth Duvall, 85, told of her family huddling under the staircase, after her father, a grocer on Main Street, came home with the store’s cash register and all the books.

The next thing she recalls is later accompanying him downtown and visiting the market, where all she can remember is the sight of "cookies and cigarettes floating” in water.

Marian Phillips, who at the time had been a teacher at the Quogue elementary school, read aloud a birthday card she received marking her 100th birthday last October from a former third-grade student, who shared his memories of the day. That included “watching these huge oak trees blow down like tooth picks. I was scared as hell,” he wrote. On a further peculiar note, she told of their spotting in a nearby pasture a corner cabinet, “the cups still hanging on the hooks. The water just let it down easy.”

The 1938 Long Island Express created this flooding scene on Westhampton Beach's Main Street, between Husty Tailor Shop and Weixelbaum Market. The Category 3 hurricane on Sept. 21, 1938, took about 60 lives on Long Island, according to the National Hurricane Center. It also created the Shinnecock Inlet.

Phillips went on to give an account of her father, a plumber, who went to secure someone’s boat.

As the water rose and “before he got home, the boat was right behind him like Bo Peep’s little sheep, following him all the way,” she said, “dragging the dock behind him.”

Jean Wilcox Tuttle, 91, told of being at home when a lull came, and her father drove off to assess conditions of the family duck farm. “We went out and ran around, as teenagers would,” she said.

“I remember seeing my father come up from the farm, and drive right through the new hedge that had been planted.”

Survivors of the Long Island Express gather Sept. 10 at the Westhampton Beach Historical Society. Credit: Randee Daddona.

His message: “We’ve got to get out of here.” He had seen “a house come over the bridge” by the farm, “and that house ended up in the duck pens,” she said.

Even those who couldn’t attend the gathering were eager to share stories.

Speaking by phone the day before, Anne S. Kirsch, 6 years old at the time, said she can’t recall if she was in kindergarten or first grade.

But, “I can still see the water coming up my driveway,” she said, as she watched through her parents’ bedroom window, not far from a creek that was connected to the boat basin.

A Dune Road home washed onto Beach Lane bridge. Credit: Westhampton Beach Historical Society.

Already her father had picked her up from school, where she recalls windows rattling so badly that she and others jumped up from their seats.

Also etched in her memory — feeling “my father carrying me in, fighting the wind, going from the garage to the back porch,” said Kirsch, who spoke by phone from Vermont where some business prevented her from returning home for the meeting.

“It was horrendous,” she said — the strong winds, the lack of warning and all that water that led to her parents losing everything and having to start over.

Kirsch said the storm taught her that while you can’t live in fear you also can’t be complacent. “You have to respect the ocean.”

Quogue Bridge was damaged in the hurricane. Credit: Westhampton Beach Historical Society.

More Info: New York State deadly storms

From the 1938 Long Island Express to superstorm Sandy in 2012, New York State has seen its share of deadly Atlantic storms. Here is a look back at six of them ...

1938: Long Island Express ... The 1938 Long Island Express created this flooding scene on Westhampton Beach's Main Street, between Husty Tailor Shop and Weixelbaum Market. The Category 3 hurricane on Sept. 21, 1938, took about 60 lives on Long Island, according to the National Hurricane Center. It also created the Shinnecock Inlet.

1944: Great Atlantic Hurricane ...New Yorkers struggle through the streets of downtown Manhattan as the Great Atlantic Hurricane hit on Sept. 14, 1944. Six people were killed in New York State, according to the National Hurricane Center, but the vast majority of the 390 deaths caused by the storm occurred at sea. Credit: AP / John Lent.

1954: Hurricane Edna ... This was the scene on one of the runways at LaGuardia Airport as the fringe of Hurricane Edna hit New York on Sept. 11, 1954. There was no flood damage reported at the field, as most planes and ground vehicles had been moved into hangars. But Edna caused six highway deaths in the metropolitan area, according to The Associated Press. Credit: AP / Harry Harris.

1999: Tropical Storm Floyd ... At the Shinnecock Inlet a boat is surrounded by water both in the bay and on Dune Road after Tropical Storm Floyd, which reached Long Island on Sept. 16, 1999. It claimed two lives in New York State, according to the National Hurricane Center. But 35 of the storm's 57 overall fatalities occurred in North Carolina, where Floyd made landfall as a Category 2 hurricane. Credit: L.I. News Daily / Daniel Goodrich.

2011: Hurricane Irene ... Jamie Young, of Bellport, and Shawn Pizzo and Mohammed Hasidi, both of Medford, make their way down a flooded Smith Street in Patchogue in the aftermath of Hurricane Irene on Aug. 28, 2011. The storm killed 10 people in New York State, including one in Suffolk County, according to the National Hurricane Center. Credit: Newsday / Thomas A. Ferrara.

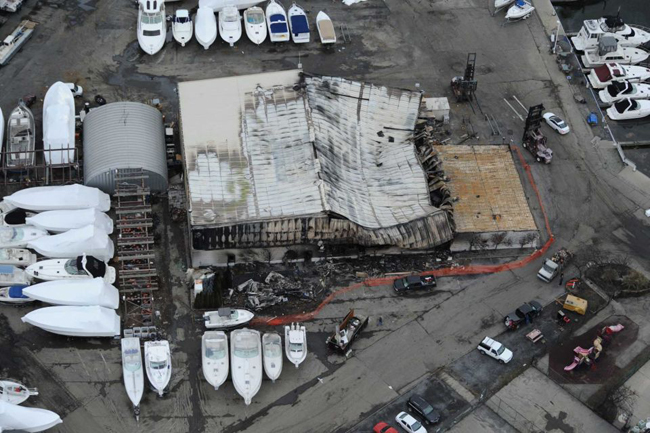

2012: Superstorm Sandy ... The area near Atlantic and Ocean streets in Lindenhurst was hit hard by superstorm Sandy, as seen in this photo from Nov. 2, 2012. Sandy was responsible for 72 deaths, including 48 in New York State, the National Hurricane Center said. Long Island recorded 13 deaths. Credit: Doug Kuntz.

More Info: New York Sea Grant

New York Sea Grant (NYSG), a cooperative program of Cornell University

and the State University of New York (SUNY), is one of 33 university-based

programs under the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s

National Sea Grant College Program.

Since 1971, NYSG has represented a statewide network of integrated

research, education and extension services promoting coastal community

economic vitality, environmental sustainability and citizen awareness

and understanding about the State’s marine and Great Lakes resources.

Through NYSG’s efforts, the combined talents of university scientists

and extension specialists help develop and transfer science-based

information to many coastal user groups—businesses and industries,

federal, state and local government decision-makers and agency managers,

educators, the media and the interested public.

The program maintains Great Lakes offices at Cornell University, SUNY

Buffalo, SUNY Oswego and the Wayne County Cooperative Extension office

in Newark. In the State's marine waters, NYSG has offices at Stony Brook

University in Long Island, Brooklyn College and Cornell Cooperative

Extension in NYC and Kingston in the Hudson Valley.

For updates on Sea Grant activities: www.nyseagrant.org has RSS, Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube links. NYSG offers a free e-list sign up via www.nyseagrant.org/nycoastlines for its flagship publication, NY Coastlines/Currents, which is published quarterly. Our program also produces an occasional e-newsletter,"NOAA Sea Grant's Social Media Review," via its blog, www.nyseagrant.org/blog.