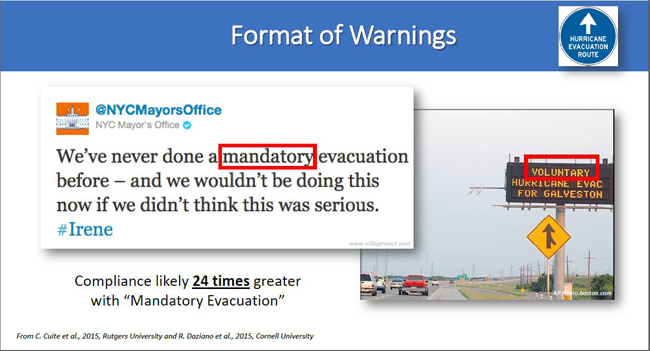

CSAP-funded researchers from Rutgers found that using the word “voluntary” in evacuation notices may result in fewer evacuations than using other similar messages. Localizing evacuation messages to town level has been shown to be important but drilling down to street level notices may not significantly improve evacuation rates. Credit: Cara Cuite/Rutgers.

— By Chris Gonzales, Freelance Science Writer, New York Sea Grant

New Brunswick, NJ, August 15, 2018 - When a hurricane approaches, communication about the dangers—such as public officials’ evacuation warnings—can mean the difference between life and death.

Researchers are trying to understand how people respond to hurricane threats and different types of messages about the risks. In a recent study funded by the Coastal Storm Awareness Program (CSAP), investigators use data from an online survey of more than 1,700 residents of coastal areas in the eastern USA. Survey respondents were asked how they would respond to different risk messages in a scenario of a hurricane approaching their area. The results could help communities prepare for—and respond to—the worst of risks.

Investigators found that messages that emphasized severe impacts of storms or dangers of bodily harm or death (called “impact” and “fear” messages, respectively) increased residents’ stated intentions to evacuate. Impact messages stress potential damage to homes, neighborhoods, and personal property. Fear messages warn of injury or death if residents do not heed warnings in messages. However, the fear appeals also increased perceptions that the information provided was “overblown,” or not credible. The impact messages did not. Meanwhile, messages that described potential for hazardous conditions such as storm surge or flooding, in addition to messages about the potential for high winds from the hurricane (called “hazard” messages) did not influence evacuation intentions.

Federal funds for the Coastal Storm Awareness Program are provided from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to the National Sea Grant College Programs in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut. Each of those states was affected by Hurricane Sandy in 2012. This survey targeted coastal residents in those states and was implemented in 2015. “Is Storm Surge Scary?” an article describing the results, is being published in the September 2018 issue of the International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction.

“The results of this research can help weather forecasters, emergency managers, and others learn how to better communicate with diverse populations about the risks posed by an approaching hurricane,” said Rebecca Morss, the article’s lead author.

Cara Cuite, Ph.D, an Assistant Extension Specialist at Rutgers University’s Department of Human Ecology, is a co-author of the article as well as a principal investigator on the related CSAP-funded project “Best Practices in Coastal Storm Risk Communication.”

To better understand the effects of hurricane risk messages, the researchers also looked at how factors unrelated to the content of the messages influenced residents’ evacuation intentions. These factors included individual differences among survey respondents, such as sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender, ethnicity, education level and income), actual and perceived flood and storm surge exposure, evacuation planning, and prior hurricane experiences.

The results show that evacuation prior to landfall of Sandy was the strongest predictor of evacuation intentions in the survey’s hurricane scenario. Other strong predictors of evacuation intentions include emotional distress due to Sandy, perceived residence in a flood zone, having an evacuation plan, and believing that one’s home had not previously flooded.

Compared to the warning messages tested, these non-message factors had a much stronger influence on evacuation intentions. In other words, impact or fear messaging alone only slightly increases risk perceptions and motivates additional people to take protective actions.

Complicating the picture, it is extremely difficult to precisely identify specific locations at high risk from hurricane hazards several days in advance, when people are making evacuation decisions, and to target warning messages to those specific areas.

These results suggest that it is important to develop more effective strategies to communicate hurricane risks in the context of these predictive uncertainties and the other factors that influence people’s risk perceptions and decisions.

This study reveals potentially important drawbacks of messages that try to scare people into taking recommended precautions. Namely, some people may try to manage their fears by discounting the legitimacy of the message, opposite of the intended effect. Ultimately, messages that evoke worry may be better motivators for some people than those that elicit fear.

References

Morssa, R. (2017). "Is storm surge scary? The influence of hazard, impact, and fear-based messages and individual differences on responses to hurricane risks in the USA." International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction: 44-58.

More Info: NOAA Sea Grant's Coastal Storm Awareness Program

The 4-1/2 minute trailer for NOAA Sea Grant's Coastal Storm Awareness Program's 23-minute documentary, view-able on YouTube.

Hurricane Sandy traveled up the Atlantic coast in late October 2012,

coming ashore as a "Superstorm" in the tri-state region. While

evacuation orders were in place, there was still significant loss of

life in flooded homes. Why didn’t or couldn’t people leave for safe

shelter?

Answering this question was at the heart of the $1.8M National Oceanic

and Atmospheric Administration-funded Coastal Storm Awareness Program

(CSAP), a series of 2014-15 social science studies administered by Sea

Grant programs in New York, New Jersey and Connecticut. Findings from

CSAP-funded investigators are shared in a 23-minute documentary short

and accompanying four-and-a-half minute trailer, which were released in

May 2016.

The goal of this suite of 10 research projects – which were

competitively funded at institutions from Yale University to Mississippi

State University via Sandy Supplemental funds appropriated by Congress

under the Disaster Relief Appropriations Act of 2013 – was to better

understand how people react to storm warnings and make the decision to

stay or to go.

For more, see www.nyseagrant.org/csap.

More Info: New York Sea Grant

New York Sea Grant (NYSG), a cooperative program of Cornell University

and the State University of New York (SUNY), is one of 33 university-based

programs under the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s

National Sea Grant College Program.

Since 1971, NYSG has represented a statewide network of integrated

research, education and extension services promoting coastal community

economic vitality, environmental sustainability and citizen awareness

and understanding about the State’s marine and Great Lakes resources.

Through NYSG’s efforts, the combined talents of university scientists

and extension specialists help develop and transfer science-based

information to many coastal user groups—businesses and industries,

federal, state and local government decision-makers and agency managers,

educators, the media and the interested public.

The program maintains Great Lakes offices at Cornell University, SUNY

Buffalo, SUNY Oswego and the Wayne County Cooperative Extension office

in Newark. In the State's marine waters, NYSG has offices at Stony Brook

University in Long Island, Brooklyn College and Cornell Cooperative

Extension in NYC and Kingston in the Hudson Valley.

For updates on Sea Grant activities: www.nyseagrant.org has RSS, Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube links. NYSG offers a free e-list sign up via www.nyseagrant.org/nycoastlines for its flagship publication, NY Coastlines/Currents, which is published quarterly. Our program also produces an occasional e-newsletter,"NOAA Sea Grant's Social Media Review," via its blog, www.nyseagrant.org/blog.