— By Chris Gonzales, Communications Specialist, New York Sea Grant

New York, NY, April 23, 2018 - In October 2012, news of Hurricane Sandy’s devastating impacts—such as flooded New York City subway tunnels, and snowstorms in North Carolina—came as a powerful storm surge overwhelmed the shores of the U.S. East Coast.

A frequently-repeated story concerned inadequate government planning and failed infrastructure. A less-often told story was about how residents perceived the risks of the storm, and how seriously they considered the option to evacuate.

In a recent paper published in Risk Analysis, a scholarly journal, Laura Rickard (Department of Communication and Journalism at the University of Maine, Orono, and formerly of the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry) and colleagues are thinking about risk judgment and risk communication in connection to natural hazards like hurricanes. They suggest in their work—which is funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), as part of the Sea Grant–administered Coastal Storm Awareness Program (CSAP)—that memories of past hurricanes may be as important in how people form risk judgments as in-the-moment reactions.

In scientific papers about natural hazards, there’s an idea called protection responsibility: The more one views oneself as responsible for protecting oneself from harm, the more likely one is to engage in preventive behaviors. For instance, surveys have shown that many people view state governments, among official actors, as most responsible for protection from earthquakes. When asked to choose among informal actors (friends, family, etc.), respondents tend to rate themselves as most responsible.

Perceptions of a natural hazard’s magnitude also may affect people’s sense of how preventable damage or harm is. For example, research in New Zealand showed that when media coverage tended to emphasize the overall magnitude of a natural disaster (an entire neighborhood destroyed), rather than the distinctiveness of the event (a particular house damaged), people might tend to think the storm was so severe that damage was not preventable.

Rickard and her team conducted a survey with over 600 respondents from the states of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut—specifically, in counties that experienced any amount of storm surge or flooding associated with Hurricane Sandy. Individuals were surveyed in the fall of 2014, only about two years after Sandy struck the East Coast, thus, the researchers posited, the storm would be part of recent memory. To measure risk judgment related to hurricanes, the researchers asked participants to rate the likelihood that “a storm like Sandy” will harm various groups such as “you and your family” or “the U.S. East Coast,” as well as the perceived severity of such a storm to these groups (i.e., not at all serious to extremely serious).

The scientists also collected data about participants’ awareness of the Sandy forecast for storm severity, general hurricane experience (“how many hurricanes have you been in?”, “how many times have you evacuated from a hurricane?”) and specific experience during Hurricane Sandy.

Then her team assessed how participants perceived their individual responsibility by measuring agreement with statements such as, “people who did not heed evacuation orders are responsible for what happened to them.”

The team found that general hurricane experience was not related to a person making internal attributions of responsibility—that is, a person who had been in a hurricane before was not more or less likely to make a judgment that someone—herself, the mayor, the president—was responsible for damage or injury from a storm.

However, those who evacuated were more likely to make such attributions.

Those who knew someone who was affected by Hurricane Sandy were more likely to report judgments of greater risk. To a lesser extent, this was also the case with people affected by hurricanes generally.

Respondents with more favorable attitudes toward hurricane information were more likely to make individual attributions of responsibility—i.e., saying people had only themselves to blame for the outcomes experienced during Hurricane Sandy.

Meanwhile, those who knew someone affected by Hurricane Sandy were less likely to “blame the individual.” Researchers suggest that these participants view themselves as similar to others impacted by the storm, and may tend to attribute unfortunate consequences of a storm to external factors, such as the storm itself, or the government.

“Some survey results confirm past research,” said Rickard. “For example, those who have experienced a natural hazard or extreme weather event tend to perceive higher risk associated with this hazard than those who have not. Other findings, however, suggest more complexity in our understanding of how recalled experience and attribution of responsibility may contribute to one’s future risk judgment.”

In conclusion, the researchers also suggest that future research might examine risk perceptions of natural hazards of a more diffuse time scale, such as sea-level rise or ocean acidification.

References

Laura N. Rickard, et al.(2017) Sizing Up a Superstorm: Exploring the Role of Recalled Experience and Attribution of Responsibility in Judgments of Future Hurricane Risk. Risk Analysis. 16 pp. DOI: 10.1111/risa.12779

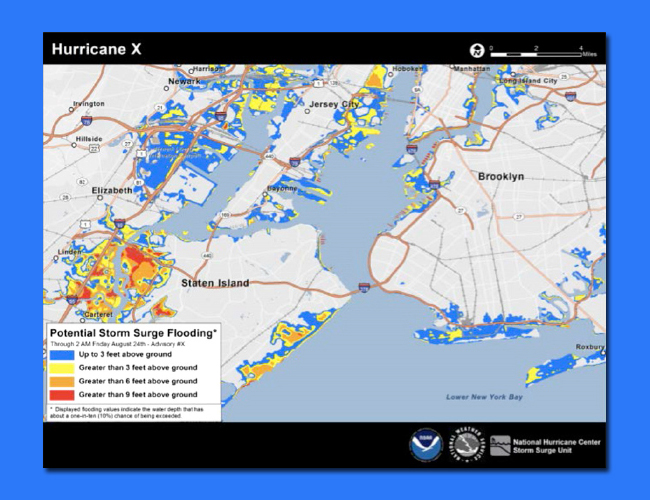

Sample storm surge inundation map, also used in the map experimental condition. Credit: Laura Rickard; NOAA National Hurricane Center.

More Info: NOAA Sea Grant's Coastal Storm Awareness Program

The 4-1/2 minute trailer for NOAA Sea Grant's Coastal Storm Awareness Program's 23-minute documentary, view-able on YouTube.

Hurricane Sandy traveled up the Atlantic coast in late October 2012, coming ashore as a "Superstorm" in the tri-state region. While evacuation orders were in place, there was still significant loss of life in flooded homes. Why didn’t or couldn’t people leave for safe shelter?

Answering this question was at the heart of the $1.8M National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration-funded Coastal Storm Awareness Program (CSAP), a series of 2014-15 social science studies administered by Sea Grant programs in New York, New Jersey and Connecticut. Findings from CSAP-funded investigators are shared in a 23-minute documentary short and accompanying four-and-a-half minute trailer, which were released in May 2016.

The goal of this suite of 10 research projects – which were competitively funded at institutions from Yale University to Mississippi State University via Sandy Supplemental funds appropriated by Congress under the Disaster Relief Appropriations Act of 2013 – was to better understand how people react to storm warnings and make the decision to stay or to go.

For more, see www.nyseagrant.org/csap.

More Info: New York Sea Grant

New York Sea Grant (NYSG), a cooperative program of Cornell University

and the State University of New York (SUNY), is one of 33 university-based

programs under the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s

National Sea Grant College Program.

Since 1971, NYSG has represented a statewide network of integrated

research, education and extension services promoting coastal community

economic vitality, environmental sustainability and citizen awareness

and understanding about the State’s marine and Great Lakes resources.

Through NYSG’s efforts, the combined talents of university scientists

and extension specialists help develop and transfer science-based

information to many coastal user groups—businesses and industries,

federal, state and local government decision-makers and agency managers,

educators, the media and the interested public.

The program maintains Great Lakes offices at Cornell University, SUNY

Buffalo, SUNY Oswego and the Wayne County Cooperative Extension office

in Newark. In the State's marine waters, NYSG has offices at Stony Brook

University in Long Island, Brooklyn College and Cornell Cooperative

Extension in NYC and Kingston in the Hudson Valley.

For updates on Sea Grant activities: www.nyseagrant.org has RSS, Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube links. NYSG produces a monthly e-newsletter, "NOAA Sea Grant's Social Media Review," via its blog, www.nyseagrant.org/blog. Our program also offers a free e-list sign up via www.nyseagrant.org/coastlines for its flagship publication, NY Coastlines/Currents, which is published quarterly.