Credit: National Sea Grant College Program.

Harmful algal blooms (HABs) and their toxins can make pets and wildlife sick (and in some cases kill them) and also pose health risks for humans.

Ithaca, NY, September 3, 2019 - Dogs can be exposed to toxins by skin contact with water contaminated with cyanobacteria or toxins, when swallowing water while playing in the water, or by licking it off fur or hair.

“Not all algal blooms are harmful,” said Jesse Lepak, Ph.D., Great Lakes Fisheries and Ecosystem Health Specialist with New York Sea Grant (NYSG), “but some dense populations of cyanobacteria, also known as blue-green algae, can produce toxins that can have serious effects on liver, nervous system, and skin of humans and their pets.”

Earlier this summer, Lepak reminded New Yorkers that a Dogs and HABs informational brochure can be downloaded via NYSG's June news item, "NYSG Says Enjoy the Water this Summer and Keep Yourself and Your Pets Safe from Harmful Algal Blooms," which also features video and audio clips explaining more about HABs.

Toxic HABs can develop in less than 24 hours, so pet owners are encouraged to avoid exposure to potential HABs which are often blue-green, but can also appear red, brown, or white. Blooms can look like spilled paint, pea soup, foam, scum, or floating mats.

The ingestion of HAB toxins can cause drooling, tremors, and seizures in dogs. Owners should take animals that have been exposed to HABs immediately to a veterinarian.

In addition to following the suggested tips in the Sea Grant brochure (pdf), dog owners are encouraged to seek immediate veterinary care if they suspect their pet has been exposed to a toxic algal bloom.

Toxic blue-green algae blooms like the ones the New Jersey Record reported in mid-August were found in two New Jersey lakes can be deadly to dogs.

Last summer, NYSG's colleagues at Lake Champlain Sea Grant adapted the brochure for its region (pdf). There's a benefit in passing this information along to other communities, as the encounters between pets and waterbodies with algal blooms knows no boundaries. That was apparent by the incidents reported by the media from areas close to New York (including Vermont, New Jersey and Pennsylvania) as well as further down the U.S. Eastern Seaboard (such as North Carolina and Georgia) and across the nation (in, for example, Illinois and Texas).

In mid-August, the

Illinois Environmental Protection Agency and Department of Public Health put out a press release to remind local residents to exercise caution if they are planning activities on the State's waterways, including lakes, rivers, streams and ponds. In addition to providing local contacts and resources, the news alert included a link to NYSG's HABs and Dogs brochure.

As reported in the video above released in mid-August by MEAWW (Media Entertainment Arts WorldWide), New York Sea Grant's Dogs and Harmful Algal Blooms brochure identifies the toxic bacteria in blooms as cyanobacteria, which can seriously harm pets.

The MEAWW clip also highlighted some recent dog deaths related to exposure to toxic HABs, which was also headline news locally, as seen in the mid-August clip below from News 12 Long Island.

Cyanobacteria are a kind of photosynthesizing bacteria that are naturally occurring in marine and freshwater ecosystems. Though not all types are harmful, some species are capable of producing toxins.

Cyanobacteria need warm water, sun and nutrients to grow. They have little air pockets that they can puff up, allowing them to float up and down in the water column. Sometimes the cells congregate together and are visible in a mass. They can look like spilled paint, chunks, wispy lines or oil.

To see the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation's map of harmful algal blooms and to report a bloom, go to www.dec.ny.gov/chemical/83310.html.

As in the case for New York's freshwater systems, harmful algae blooms have also tainted various Long Island waters for years. In late August, Stony Brook University professor Chris Gobler spoke with Newsday (a daily Long Island newspaper and digital media source) about how Suffolk County consistently tops the state's counties in the number of ponds, lakes and other fresh waters colonized by cyanobacteria.

It's stated in the clip above that Gobler has been testing waters for this algae since 2003. Many of his studies over the years to better understand the different kinds of algal blooms (which, again, are not all harmful) have been funded by New York Sea Grant.

For humans, the toxins of cyanobacteria are usually not lethal but cause skin irritation or gastrointestinal problems, such as diarrhea and vomiting, authorities said. Other toxins from the blue-green algae can paralyze the nervous system, including shutting down the ability to breathe. But for dogs and likely other animals, the cyanobacteria is often fatal.

State health and environmental officials have seen the number and locations of blooms rise since they started monitoring the problem at least seven years ago — almost 400 freshwater bodies so far. The state in June launched a new reporting system for harmful algae blooms, or HABs, including a map of affected waters, and publicized its slogan of “Know it, Avoid it, Report It."

As seen below in this late August clip, Gobler discussed the issue of HABs at Agawam Park in the village of Southampton, where the lake there resembled pea soup. He said to News 12 Long Island that the algae blooms "can make toxins that are a human health threat. It can also be harmful to animals, specifically pets."

In the upper portions of New York State, the Post Star — based in Glens Falls, NY (a city on the Hudson River, in the Adirondack foothills, at the border of the State's Saratoga County) — reported on July 23rd that two dogs likely died after ingesting harmful algal bloom toxins earlier in the month from a private Vermont pond.

“For pet owners, you want to avoid it, that’s pretty much all there is to it,” said Karyn Bischoff, a toxicologist with Cornell University’s College of Veterinary Medicine, referring to small watering holes and ponds, as they can become filled with cyanobacteria blooms.

Two toxins, microcystin and anatoxin, are of the most concern in New York. Microcystin is a liver toxin and anatoxin is a neurotoxin.

Bischoff, who was an advisor on both NYSG's 2014 original and 2017 revised versions of the HABs and Dogs brochure, said both are “surprisingly fast-acting,” especially if a dog licks its fur and gets a concentrated dose.

“In one case of cyanobacteria (poisoning), the person had two pet dogs,” Bischoff said. “They came out of a lake covered with cyanobacteria. He (the owner) grabbed the hose and hosed one of them down, but by the time he went to hose the other one, it was dead.”

Those poisoned by microcystin experience pooling of the blood.

Those poisoned by neurotoxins experience over-stimulation, Bischoff said. An animal may go through excessive salivation and tearing, urination and diarrhea. The nerves are firing so quickly that they wear out, and eventually the animal dies from respiratory paralysis, she added.

Researching HABs

Greg Boyer, a professor and scientist and SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, has been studying cyanobacteria for decades. Boyer is another advisor on both versions of the NYSG HABs and Dogs brochure.

Every once in a while, a pet owner or vet will reach out to him about a dog that is ill or dead, possibly from cyanotoxins.

Boyer said he is working with some vets on a possible urine analysis as a way to test a sick dog for the toxins. It’s not easy, however.

“Most people don’t realize that type of work, what’s called ‘untargeted discovery,’ is very, very time consuming,” Boyer said. “We’ve had samples we’ve worked on for six months.”

Once an animal ingests the toxin, the body will try to detoxify it, Boyer explained. That could modify the toxin, making it difficult to test for directly.

Testing the water source is also costly and can be time consuming.

That’s what is frustrating for Bischoff when trying to diagnose an animal that could be poisoned by cyanobacteria toxins. The state does not test every bloom, so without waiting for clinical signs, vets have no way of knowing if a pet was exposed to the liver or neurotoxin.

What You Can Do

If you didn’t keep your dog on a leash before checking the water and it jumped into a bloom, Bischoff said the first thing to do is get it out of the water and rinse it off.

Not all cyanobacteria blooms have toxins, either. Bischoff said to monitor the dog and look for symptoms.

If you do suspect your pet has ingested toxins, get it to the vet.

Bischoff said veterinarians may want to test for liver enzymes. They may give the pet a dose of activated charcoal or something similar, which binds to the toxins and helps them pass through.

If the dog ingested a neurotoxin, the vet may sedate the animal until it gets through the extreme stimulation. The goal will be to keep the animal breathing, too.

Know It, Avoid It, Report It

HABs may make the water look bright green or like pea soup. They may look like green dots, clumps or globs on the water surface. For more images of toxic algae, as well as non-toxic algae for comparison, see the NYS Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) Photo Gallery. Credit: NYS DEC.

As reported by Nyack News & Views in late August, when it comes to HABs, the Department of Environmental Conservation encourages New Yorkers to “KNOW IT, AVOID IT, REPORT IT.”

KNOW IT – HABs vary in appearance from scattered green dots in the water to long, linear green streaks, pea soup or spilled green paint, to blue-green or white coloration.

AVOID IT – People, pets, and livestock should avoid contact with water that is discolored or has algal scums on the surface.

REPORT IT – If members of the public suspect a HAB, report it through the NYHABs online reporting form available on DEC’s website.

The New York State Department of Health provides more "Know It, Avoid It, Report It" information on blue-green algae blooms at www.health.ny.gov/environmental/water/drinking/bluegreenalgae.

Other Resources

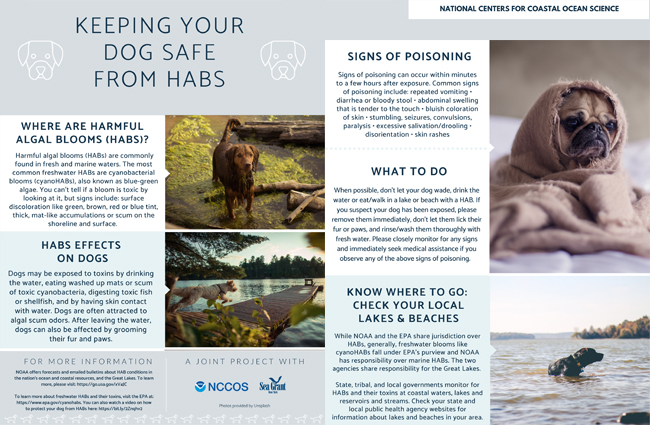

A full transcript of the above infographic, "Keeping Your Dog Safe From HABs," follows this section. Credit: NOAA National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science.

You can find helpful information from a number of reliable sources, including the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science (which released its HABs 101, "Protecting Your Dog from Harmful Algal Blooms: Information and Resources," in mid-August) and Cornell Cooperative Extension of Tompkins County's "Harmful Algal Blooms."

Both sources cite NYSG's HABs and Dogs brochure as one of its valuable resources.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency calls out nutrient pollution into our waterways as a widespread problem, as it gives fuel to algal blooms. Besides affecting recreational use of waterways, it can threaten drinking water quality, making treatment more costly. EPA offers more information and actions you to take at www.epa.gov/nutrientpollution.

Infographic: Keeping Your Dog Safe From HABs

Where are harmful algal blooms (HABs)?

Harmful algal blooms (HABs) are commonly found in fresh and marine waters. The most common freshwater HABs are cyanobacterial blooms (cyanoHABs), also known as blue-green algae. You can't tell if a bloom is toxic by looking at it, but signs include: surface discoloration like green, brown, red or blue tint, thick, mat-like accumulations or scum on the shoreline and surface.

HABs Effects on Dogs

Dogs may be exposed to toxins by drinking the water, eating washed up mats or scum of toxic cyanobacteria, digesting toxic fish or shellfish, and by having skin contact with water. Dogs are often attracted to algal scum odors. After leaving the water, dogs can also be affected by grooming their fur and paws.

Signs of poisoning

Signs of poisoning can occur within minutes to a few hours after exposure. Common signs of poisoning include: repeated vomiting • diarrhea or bloody stool • abdominal swelling that is tender to the touch • bluish coloration of skin • stumbling, seizures, convulsions, paralysis • excessive salivation/drooling • disorientation • skin rashes

What to do

When possible, don’t let your dog wade, drink the water or eat/walk in a lake or beach with a HAB. If you suspect your dog has been exposed, please remove them immediately, don’t let them lick their fur or paws, and rinse/wash them thoroughly with fresh water. Please closely monitor for any signs and immediately seek medical assistance if you observe any of the above signs of poisoning.

Know where to go

Check your local lakes & beaches: While NOAA and the EPA share jurisdiction over HABs, generally, freshwater blooms like cyanoHABs fall under EPA's purview and NOAA has responsibility over marine HABs. The two agencies share responsibility for the Great Lakes. State, tribal, and local governments monitor for HABs and their toxins at coastal waters, lakes and reservoirs and streams. Check your state and local public health agency websites for information about lakes and beaches in your area.

For more information

NOAA offers forecasts and emailed bulletins about HAB conditions in the nation’s ocean and coastal resources, and the Great Lakes. To learn more, please visit: go.usa.gov/xV4JC.

To learn more about freshwater HABs and their toxins, visit the EPA at: www.epa.gov/cyanohabs. You can also watch a video on how to protect your dog from HABs here: bit.ly/2Znqhv2.

More Info: New York Sea Grant

New York Sea Grant (NYSG), a cooperative program of Cornell University

and the State University of New York (SUNY), is one of 33 university-based

programs under the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s

National Sea Grant College Program.

Since 1971, NYSG has represented a statewide network of integrated

research, education and extension services promoting coastal community

economic vitality, environmental sustainability and citizen awareness

and understanding about the State’s marine and Great Lakes resources.

Through NYSG’s efforts, the combined talents of university scientists

and extension specialists help develop and transfer science-based

information to many coastal user groups—businesses and industries,

federal, state and local government decision-makers and agency managers,

educators, the media and the interested public.

The program maintains Great Lakes offices at Cornell University, SUNY

Buffalo, SUNY Oswego and the Wayne County Cooperative Extension office

in Newark. In the State's marine waters, NYSG has offices at Stony Brook

University in Long Island, Brooklyn College and Cornell Cooperative

Extension in NYC and Kingston in the Hudson Valley.

For updates on Sea Grant activities: www.nyseagrant.org has RSS, Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube links. NYSG offers a free e-list sign up via www.nyseagrant.org/nycoastlines for its flagship publication, NY Coastlines/Currents, which is published quarterly. Our program also produces an occasional e-newsletter,"NOAA Sea Grant's Social Media Review," via its blog, www.nyseagrant.org/blog.